The Politics of Israel’s 2014 Memory Law: Integrating the Forgotten Histories of Jews from Arab and Muslim Countries

The 2014 Israeli memory law making November 30 the Day to Mark the Departure and Expulsion of Jews from the Arab Countries and Iran was initially presented as belated recognition of long-marginalised communities. Yet beyond historical justice, the law reflects broader political motives shaping Israel’s expanding landscape of memory legislation with the aim of consolidating a particular national narrative. By examining the history of the Syrian Jews, this blog article shows how the law acknowledges past injustices while flattening diverse experiences into a single national narrative. The case illustrates not only how commemoration becomes a political tool, but also how Jewish histories are reframed in ways that shape identity, belonging, and the contours of collective memory.

When the Israeli Knesset passed the Law for the Commemoration of the Departure and Expulsion of Jews from Arab Countries and Iran in July 2014, it designated November 30 as a National Day of Commemoration. Initially, the law was represented as long-overdue recognition of the displacement of around 850,000 Jews from Arab and Muslim countries between 1947 and 1972. The Mizrahi Jews – literally “Jews from the East” in Hebrew – were expelled or fled escalating violence persecution in several wave, primarily during the establishment of the State of Israel and the three Arab–Israeli wars (1948, 1956, 1967). In the decades preceding the passing of the law these communities had been marginalised within Israel’s national narrative shaped by jews stemming from Europe – the Ashkenazi – and their experiences and memory of the Holocaust.

The bill was initiated primarily by two members of the Israeli Knesset (MKs), Shimon Ohayon and Nissim , both descendants of Jewish immigrants from Morocco and Iraq. Ohayon was born in 1945 in Marrakesh, Morocco, and immigrated to Israel with his parents in 1956. He is the chairmen of the Center for Moroccan Immigrants in Israel, a local Israeli organisation which aims to preserve Moroccan Jewish music and culture and supports the integration of Moroccan Jews into higher education, including medical schools. Ze’ev was born in Jerusalem in 1951. His parents immigrated to Mandatory Palestine from Iraq in 1941.

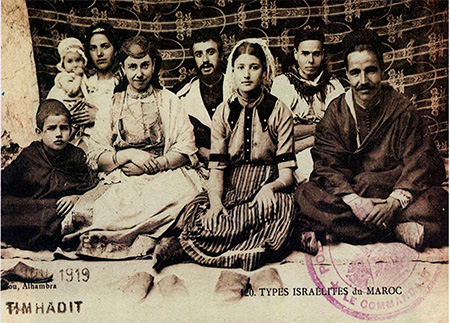

Moroccan Sephardi Jews. 1919. Public domain. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Both MKs represent the first generation of Jewish immigration from Arab countries. They view the preservation of their communities’ histories and family narratives as essential to integrating Mizrahi experiences into the broader Israeli Jewish and Zionist narrative. It is against this backdrop of cultural revival and political recognition that the 2014 law should be understood.

However, this law should also be understood as part of a wider trend of using legislation to shape collective memory in Israel, extending beyond simply filling gaps in the country’s collective memory or acknowledging past injustices. This blog explores how the law standardises the diverse histories of Jews from Arab and Muslim countries. Through the case of Syrian Jews, it shows how selective commemoration supports contemporary political narratives while overlooking complex communal histories across the Middle East. As part of a broader pattern of legislative attempts to shape collective memory in Israel, the 2014 law went beyond redressing gaps in Israel‘s collective memory and acknowledging historical injustices.

Constructing a Shared National Narrative

The legislation’s stated goal was to bring long-neglected histories of Middle Eastern Jewish communities into the centre of Israeli remembrance. Yet the law must also be understood against the backdrop of a broader trend in Israeli memory politics.

Over the past two decades, Israel has passed several laws that regulate or institutionalise remembrance, including the Nakba Law, which restricts public commemoration of the Nakba (“the catastrophe”), the term used to describe the forcible displacement of around 700,000 Palestinians during the 1947–48 war and the creation of the State of Israel. Alongside this, the Nation State Law, which defines Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people. Together, these laws aim to consolidate a coherent national narrative, strengthen the Jewish character of the state, and narrow the space for competing historical accounts.

The 2014 memory law fits into this broader legislative context and emphasises Jewish belonging, both Ashkenazi and Mizrahi, to the State of Israel as the state of the Jewish people. The 2014 legislation also adopts the term “Jewish refugees”.

This wording mirrors the Palestinian refugee narrative and introduces a symbolic parallel between the displacement of Jews from Arab lands and the displacement of Palestinians during the 1948 war. In this sense, the law serves both commemorative and political functions. It elevates the status of Mizrahi histories while reframing the Israeli–Palestinian conflict through the lens of a regional population exchange.

The logic of this framing stems from American legislation in the United States Congress. A 2008 United States Congressional resolution also linked any resolution of Palestinian refugee claims to recognition of Jewish losses in Arab states. In both cases, memory and diplomacy intertwine, while commemoration becomes an instrument of a political strategy rather than a means of historical repair.

The “Refugee” Label and Its Limits

The law’s broad classification of all Jews from Arab countries as refugees is historically contested. There is no doubt that many of the Mizrahi Jews experienced violence, persecution, or discriminatory policies. Yet, not all were victims of forced migration. Many migrated voluntarily, often decades before 1948, or moved to destinations outside Israel, such as the United States, France, Mexico, and Latin America. This raises a broader conceptual challenge: how do we determine who qualifies as a refugee in the first place?

Widely debated in migration and international law research, the concept is shaped by legal frameworks, the political interests of nation-states and international organisations, and ongoing discussions about what constitutes forced versus voluntary migration.

As with similar concepts like terrorism or genocide, definition is a complex problem upon which scholars, practitioners, and policymakers seldom agree. These definitional ambiguities become even more pronounced when examining specific cases, such as the Jews of Syria.

The Instructive Case of the Syrian Jews

Syrian Jews remain one of the less well-known Middle Eastern Jewish communities, yet their history is crucial for understanding the political logic behind the 2014 memory law and their experience highlights several contradictions in the law’s narrative.

First, Syrian Jewish migration to other countries predates the establishment of Israel. This challenges the idea that persecution after 1948 was the primary cause of displacement.

Jewish migration from Aleppo and Damascus began in the late nineteenth century, long before the rise of Arab nationalism or the establishment of the State of Israel. These movements often reflected economic ambition, social mobility, and global trading networks. Because the migration cannot always be connected to political coercion, the refugee category captures only part of this history. Thus the risk remains that using it can flatten diverse experiences into a single narrative that aligns with contemporary political needs.

Second, many Syrian Jews did not view Israel as the natural or inevitable destination. Brooklyn, Mexico City, Manchester, and Buenos Aires all became major centres of Syrian Jewish life, underscoring the transnational character of this community.

Third, for the smaller community that remained in Syria after 1948, state policies created severe restrictions on movement and property rights. Only in the early 1990s were they permitted to leave, on the condition that they renounce citizenship and forfeit their property. While this part of the story does resonate with the law’s framing of expulsion, it represents only one chapter of a much longer history.

Taken together, these dynamics make Syrian Jews an instructive case for examining how the 2014 law compresses varied and multi-layered histories into a single national story.

Recognition, Equivalence, and the Nakba

To understand the political implications of memory legislation in Israel it is essential to consider both the 2014 law and the Nakba Law of 2011. The Nakba Law restricts public funding for institutions that commemorate the displacement of Palestinians in 1948. Seen in this context, the 2014 law does not merely create a parallel Jewish refugee narrative. It also works to diminish the centrality of the Palestinian refugee experience in public discourse.

By presenting Jews from Arab countries as victims of the same historical moment, the law contributes to the framing of 1948 as a symmetric regional displacement. This reframing supports a political narrative that emphasises mutual suffering and minimises the claim that Palestinians are a uniquely displaced people.

In doing so, the law condenses diverse Mizrahi histories into a narrative that resembles the persecution-focused memory of European Jewry. The result is a simplified account that serves broader political goals while obscuring the complexity of Jewish life in the Middle East.

The Limits of Symbolic Commemoration

Although well intentioned in seeking to provide the Mizrahi Jews with long-overdue and deserved recognition, the 2014 law faces several limitations. It does not provide guidelines for implementing curricula, supporting research, or developing public education programmes. Its impact therefore remains largely symbolic, reinforcing uneven patterns of remembrance that have characterised Mizrahi histories for decades.

Ultimately, the 2014 memory law reflects an effort by Mizrahi politicians to secure long overdue recognition for their communities. Yet it also reveals an underlying pattern of instrumentality in the Israeli memory legislation that has shaped national identity and political authority for the last two decades. The case of Syrian Jews illustrates how diverse histories can be selectively reassembled to support contemporary nationalistic or patriotic narratives.

The tension between recognition and simplification illustrates how memory laws operate simultaneously as tools of commemoration and mechanisms of boundary-making. They acknowledge neglected communities, yet they also determine who counts, which histories are centred, and how the nation imagines both its past and its future.

This research was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG), Project Number 528814864.

Series

Related Posts

Tags

Author(s)

Eldad Ben Aharon

Latest posts by Eldad Ben Aharon (see all)

- The Politics of Israel’s 2014 Memory Law: Integrating the Forgotten Histories of Jews from Arab and Muslim Countries - 28. November 2025

- The Politics of Silence in Turkey: The Armenian Genocide on Its 110th Anniversary and a Memory Under Siege - 22. April 2025

- Outlook on German-Israeli Relations: German Staatsraison and Netanyahu‘s Coalition Contentious ‚Judicial Reform‘ - 6. July 2023