Political Corruption and Violence in the Philippines: Personality and Environment

The persistence of political corruption and violence in the Philippines is best understood as habitual individual adaptation to a criminogenic environment. Actions arise from the interaction between personal values and the moral norms of the surroundings; between what people see as right and what their environment treats as acceptable. In the Philippines, permissive societal and elite social norms make political corruption – and to a lesser extent, violence – appear justifiable and ordinary, thereby reinforcing weak law enforcement by eroding the moral authority of the law.

Corruption and Political Violence in the Philippines

Corruption and political killings are an enduring background of Philippine politics. Scandals and misuse of public funds recur regularly, while violence, whether linked to elections or carried out through targeted assassinations, remains a fixture of political life. Neither is confined to particular administrations; both are built into the country’s modern political history.

This text complements the analysis of institutional frameworks with a criminological approach that treats corruption and violence as rule-breaking, shaped by the interplay between individual traits and environment. Situational Action Theory (SAT), developed by Per-Olof Wikström, offers a lens for understanding why people follow or violate moral rules, viewing crime as a specific subset of moral rule-breaking.

Why People Break the Law: Situational Action Theory

SAT asks which conditions lead people to perceive and choose law-breaking as a viable option in a given situation. Politicians breaking the law are seen as following the same logic as other offenders, who perceive crime as an option and choose to violate the law. In the Philippine context, this means examining why politicians deliberately violate laws against corruption and murder.

SAT, claiming to be a general theory of moral action, argues that acts of crime are moral actions arising from the “interplay between common moral rules of conduct and a person’s own moral rules.”

Crucial is whether rule-breaking is perceived as feasible, which depends on individual propensity – shaped by values and self-control – and on criminogenic environmental features that encourage, enable, or fail to deter criminal behavior. Motivation stemming from opportunity or provocation is a precondition, as illustrated by seeing a wallet full of cash and feeling tempted to take it, or by being provoked by a serious insult. Counteracting acts of rule-breaking are internal self-control and external deterrence, whether formal (laws, sanctions) or informal (environmental norms and social expectations). Law-abiding or law-violating actions result from this interplay of individual morals and environmental norms and sanctions. However, not all rule-breaking is deliberate; moral habits learned in permissive environments often guide automatic behavior. Decisions typically blend habituation and conscious choice. Permissive combinations of personal morals and environmental features tend to produce habitual law-breaking; non-permissive combinations lead to habitual law-following; intermediate combinations suggest conscious choice.

Applying this framework to Philippine political corruption and violence highlights two interdependent dimensions. On the one hand, enabling conditions – opportunities that make corruption and violence possible – create situations in which rule-breaking appears attractive. On the other hand, controlling conditions – the formal and informal controls that should deter such behavior – prove weak or absent.

Opportunity as Enabling Condition

In the case of corruption, the role of opportunity is evident. Filipino politicians at all levels have frequent opportunities for corrupt practices, enabled by a political system enabled by a political system that grants broad discretion over various forms of allocable public funds and a tradition of personalized politics facilitating the diversion of public resources.

The same logic extends to targeted violence against political rivals. While not every killing of a politician or candidate is politically motivated, the majority can reasonably be assumed to be so. The Philippines’ long-standing prevalence of private armed groups (PAGs), personal bodyguards, and hired guns creates a structural environment where violence remains feasible and available. Throughout modern Philippine history, politicians have consistently exploited these opportunities, producing a recurring pattern of corruption and fatal political violence.

Motives underlying opportunity are more challenging to assess. They cannot be reconstructed from politicians’ morally appropriate self-portrayals, but can only be inferred from context and outcomes. Simply put, the pursuit of power and wealth plausibly explains both corruption and targeted violence. While these motives are not unique to the Philippines, they become realistic ways of maintaining or achieving status and resources in the Philippine context discussed below.

Controlling Conditions: Failure of Formal and Informal External Controls

Except for the strength of his own moral rules, the most immediate factor shaping an individual’s deliberation about wrongdoing is the likelihood of facing negative consequences. Two dimensions are central: 1) the capacity of the state and its institutions to enforce official norms through law enforcement, and 2) the distance between formal and informal norms, the gap between legal prohibitions and the attitudes of peers or the wider public, which may tolerate or even support infractions and thus normalize violations of the law.

The Philippines illustrates the failure of formal institutions to enforce rule-abiding behavior among politicians via regular punishment of breaches of the law. Corruption and targeted killings are rarely spontaneous. Typically, they are deliberate acts and thus open to cost-benefit calculations, providing for a high potential for deterrence by effective law enforcement. Yet law enforcement remains weak in these spheres. Sanctions against politicians for corruption do exist but are rare, slow, and often inconclusive. Far more visible are those cases where politicians escape punishment entirely. This pattern is even stronger in political killings, where opportunity meets near-total impunity, as masterminds remain unidentified in almost all cases. While from 2010 to 2024 almost 1400 incumbent politicians and candidates and 235 former office-holders have been killed in assassinations with a further 464 surviving wounded or unharmed (i.e. an average of 140 victims per year), the number of masterminds convicted by a court has been, to the knowledge of the author, close to zero.

Thus, in the Philippines a structural environment combining abundant opportunity with pervasive impunity turns corruption and violence into high-gain, low-risk endeavors, thereby sustaining both practices.

This is reinforced by a normative climate of high permissiveness toward corruption and violence as tools for personal gain or social control. Whereas weak law enforcement undermines deterrence at the outcome level, permissive informal norms weaken law abidance already at the perceptual level, making rule-breaking appear acceptable or even justified.

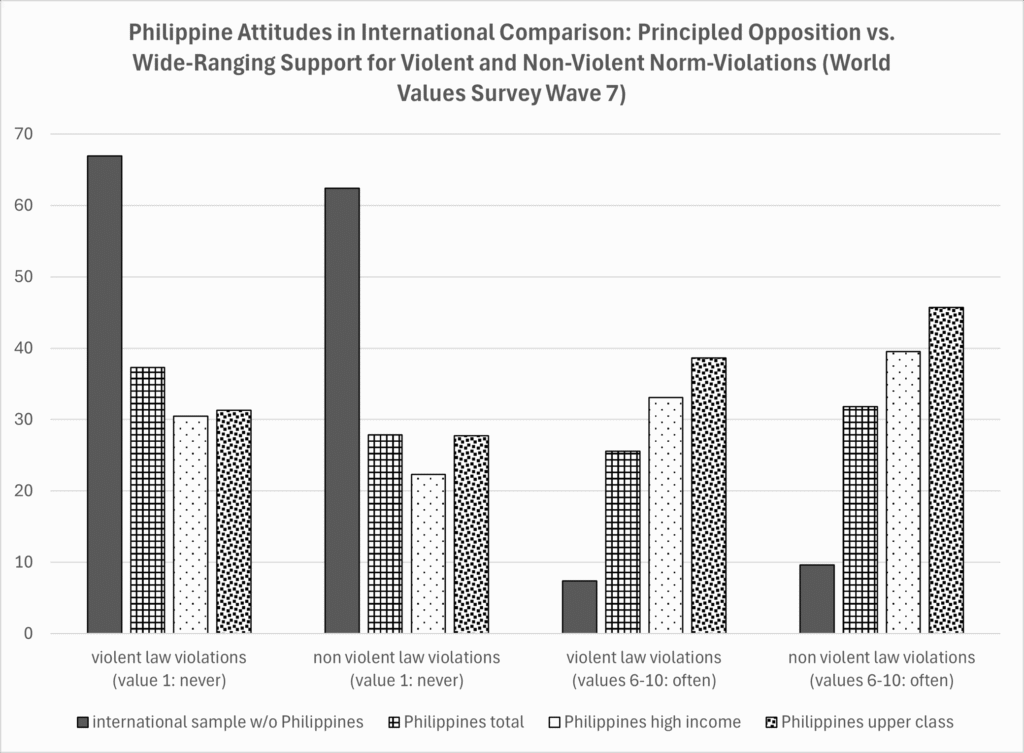

Data from the World Values Survey (WVS) underline this permissiveness. In international comparison, Filipinos stand out for granting broad justifiability to both violent and non-violent violations of norms and laws. The WVS asks respondents to rate the justifiability of acts such as violence against others, domestic violence, political violence, terrorism, theft, tax evasion, bribery, and fare-dodging on a scale from one (never justifiable) to 10 (always justifiable).

Two results stand out. First, the proportion of Filipino respondents who categorically reject any justification for norm and law violations is only about 50% of the international average (the WVS international sample spans roughly 60 to over 90 countries). Second, the proportion of Filipinos who view a wide range of situations as justifying such behavior is more than 300% of the international mean – i.e., roughly three times higher than the global average. This suggests a moral environment highly permissive of both corruption and political violence.

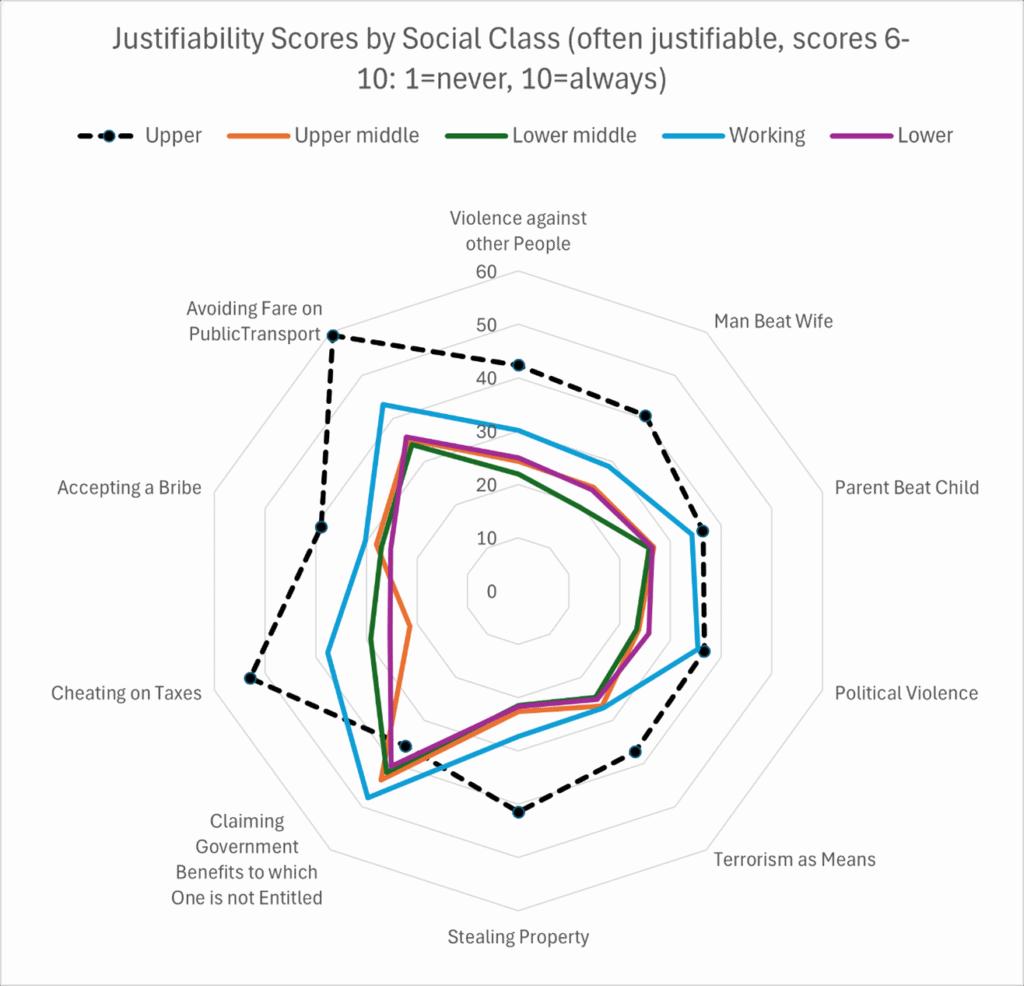

Within the Filipino sample, permissive attitudes are most pronounced among respondents with high income and those identifying as upper class, implying that the social peers of political elites hold the most tolerant views of wrongdoing. The WVS-data “spider web” diagram (below) shows that more than one-third of upper-class respondents find ample justification for political violence and terrorism, about 40 percent for theft and bribery, and over half for tax evasion.

In the Philippine environment, corruption and violence are often tolerated or justified. Everyday experience shows officeholders that many of their colleagues use both formal and informal powers to enrich themselves. In such a context, it takes strong personal morals not to take advantage of the opportunities offered by a political position.

Thus, to a significant share of officeholders, law breaking becomes a habitual act justified by the perceived permissibility of the environment and the assumption that most others do the same.

One striking example of the extent of environmental permissiveness is the case of former President Joseph Estrada. In 2007, he was convicted of plunder and sentenced to Reclusion Perpetua (i.e., a minimum of 30 years in prison), yet he was pardoned by the President just weeks after his conviction, due to his age and his promise “to no longer seek any elective position or office.” Remarkably, three years later, he placed second in the 2010 presidential election, garnering 26 percent of the vote. He subsequently won the mayoralty of Manila in both 2013 and 2016. Other notable instances include the repeated election of former coup leaders to the Senate – one entering politics shortly before being pardoned, another while still in detention. More recently, in 2025, Ronald dela Rosa, former Director of the Philippine National Police and the architect and executor of the deadly war on drugs during the early Duterte administration, was reelected Senator, receiving the third-highest number of votes.

While weak enforcement undermines compliance by signaling that law-breaking is a low-risk, high-reward choice, the permissive normative climate erodes adherence from the outset by questioning the validity and relevance of legal norms – signaling that even serious violations of the law will not incur social ostracism, either at the polls or amongst the peers.

A Criminogenic Polity

Approaching corruption and political violence as forms of crime – rule-breaking behavior shaped by the same moral and situational dynamics as ordinary offenses – highlights the role of a criminogenic environment.

Viewed through the lens of Situational Action Theory, the endurance of corruption and political violence in the Philippines appears less as a product of exceptional individual depravity than of routine adaptation. When opportunity abounds and the prevailing moral environment is permissive, transgression becomes habitual, sustained by societal and elite attitudes that often justify rather than condemn law-breaking. In such a context, corruption and violence cease to appear deviant and instead become ordinary, even rational, elements of political conduct.

Series

Related Posts

Tags

Author(s)

Latest posts by Peter Kreuzer (see all)

- Political Corruption and Violence in the Philippines: Personality and Environment - 6. November 2025

- Déjà Vu: The Flood of Corruption Engulfs the Philippines Again - 15. October 2025

- The Arrest of Rodrigo Duterte: A Turning Point for Justice and Accountability? - 12. March 2025