Dealing with Germany’s First Genocide: Why Bilateral Negotiations with Namibia Failed and What the New Government Must Do

Since the end of the last Bundestag session it has become clear that although projected in the coalition agreement, the Scholz government has not taken significant steps towards dealing with Germany’s colonial past in Namibia. A Joint Declaration fell victim to the early elections in Germany. This Spotlight presents data from a representative survey showing that dealing with the colonial past in Namibia has no priority for Germans, which might explain why the Scholz government shied away from making the case an election issue. The Spotlight identifies key take-away points on what went wrong and what a new German government should do better.

In August 1904, General von Trotha issued an extermination order against the Ovaherero in Deutsch Südwestafrika, today Namibia.1 After rising against German rule, roughly 100.000 Nama and Ovaherero fell victim to German troops, hunger, thirst and rough conditions in concentrations camps. Although recognized as a genocide by the United Nations in the 1980’s, it took another three decades until the German government took responsibility. Negotiations to deal with the colonial past were started in 2015 by Merkel’s third administration. Since then, there has been a broad consensus among the governing parties (Christian and Social Democrats until 2022 and Social Democrats, Greens and Liberals 2022-2025) to continue this course and come to terms with the colonial past – a policy in line with Germany’s commitment to transitional Justice2 and honest dialogue with African partners.3 The resulting Joint Declaration of both governments would have been a rare example of a former colonial power apologizing for its atrocities – even if it remains largely symbolic for the transformation of the post-colonial relations between both countries and their citizens.

In the declaration, the German government would have apologized for “events that, from today’s perspective, would be called genocide.” It further included a one billion Euro reconstruction and development program to assist descendants of particularly affected communities, and another 50 million for research and reconciliation projects. Right from the start, however, the German approach was limited. On the one hand it was procedurally limited to bilateral government negotiations. On the other hand, its content was limited to a rather moral discourse which categorially ruled out legal obligations.4 This approach ultimately backfired. In Namibia, representatives of the affected Nama and Ovaherero communities questioned the legitimacy of the results, since they did not feel represented in the process. Further, they demanded a confession of guilt in a legal sense, and, consequentially, reparations. Due to these unsettled issues, the Declaration has been further delayed and not yet been adopted by the Namibian Parliament. Ultimately, however, the Declaration stalled since the German government shied away from the German public. Against the background of the early end of the Ampel-Coalition and the snap elections, neither the Green Party nor the Social Democrats seemed to have been willing to make the genocide in Namibia an election issue. Results from a representative survey conducted in December 2024 can give us some hints as to why.

The Heart Does Not Grieve over What the Eye Does Not See: What Germans Know And Think About The Colonial Past in Namibia

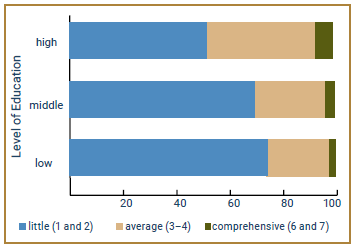

For nearly a century, Germany’s colonial past, including its occupation of Deutsch-Südwestafrika, was considered closed.5 Having lasted only a comparatively short period of time, Germans perceived it to be negligible. Further, the two world wars, the Holocaust and the German reunification obscured the colonial past in the collective memory, so that some contemporaries even speak of a colonial amnesia.6 Although the topic has become increasingly the focus of academic research and political debate since the early 2000’s, so far this knowledge has not resonated with the broader German society. Being asked how much they know about Germany’s colonial past in Namibia, 65 percent of the respondents of the survey – conducted in December 2024 – answered with “hardly anything”. In contrast, only 5 percent stated that they had comprehensive knowledge. Unsurprisingly, education matters. As depicted below, nearly half of the respondents (48 percent) with a high level of education (extended vocational training or university degree) reported to have at least an average, and 7 percent, a comprehensive knowledge of the colonial past. These numbers drop to 26 and 3 percent for respondents with low levels of education (secondary school).

This general lack of knowledge has consequences on how Germans evaluate the colonial past. When asked whether “the colonial wars against the Nama and Herero constitute genocide by today’s standards?” – the same formulation used in the Joint Declaration – 56 percent of respondent did not feel confident enough to answer. Amongst those who have a position on the issue, 37 percent supports, and 7 percent rejects this position. Compared to numbers revealed by a survey of the Jewish Claims Conference (JCC) from 2023 on holocaust remembrance, these figures are low. According to JCC,10 percent of Germans have never heard of the holocaust while one percent label it as a myth.7

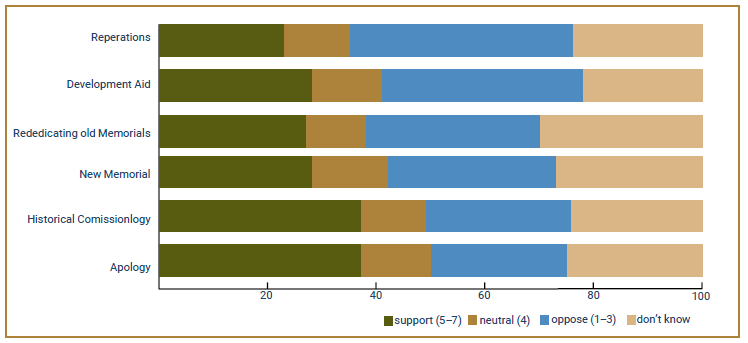

The overall low numbers of people recognizing the genocide might explain why the remnants of the Ampel-government backed away from trying to adopt the Joint Declaration before the elections. In times of budgetary constraints and polarised debates about the need for and extent of development aid the question of taking responsibility for events that happened 100 years in the past is hardly an election winning issue. This becomes even clearer if we follow the causal path of the mechanism linking knowledge on the colonial past and the willingness to support reconciliatory measures. The survey offered a wide range of potential measures ranging from symbolical gestures (official apology by the German government), measures in the field of memory and educational politics (building and rededicating memorials or appointing a historical/schoolbook commission) to restorative measures (paying official development aid or reparations to the descendants of victims). The figure below shows which measures Germans do support or oppose.

Again, between 20 and 30 percent of the respondents were unable or unwilling to answer the question. Generally, Germans seem to be more open towards symbolical measures and less open to payments. As the figure depicts, an official apology by the German government is supported by 37 and rejected by 27 percent. In comparison, direct reparations to affected communities are only strongly supported by 23 while strongly rejected by 41 percent. The payment of development aid to the Namibian Government– as envisioned in the Joint declaration – receives slightly more support: Roughly every third German (28 percent) supports this measure to come to term with the past while 37 percent reject it.

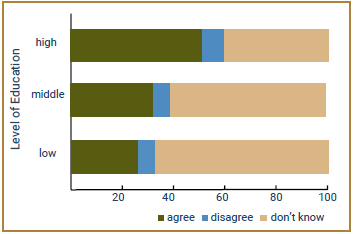

The survey shows that formal education has a huge influence on both the recognition of the genocide and respondents’ willingness to support measures of reconciliation. Among the highly educated every second acknowledged the genocide while 9 percent reject the formulation that the colonial wars can be seen as genocide. Compared to 26 percent acknowledgement and 8 percent rejection amongst the respondents with a low level of education, this is a huge improvement. Nevertheless, even among the highly educated Germans the rate of respondents being unable or unwilling to answer the question remains relatively high (41 percent).

Besides formal education, age also matters. Firstly, and independently of education, the age cohort of 18 to 29-year-olds showed above-average levels of agreement with the statement that the colonial wars constituted a genocide (42 percent). This can be explained by the changes in history lessons and corresponding history books since 2000.8 With 46 percent, this age group also has the lowest number of “don’t know” answers, which indicates that people of this generation have both, the necessary information and the need to form an opinion on this question. In addition to the age cohort of young adults, the age cohort of over 70-year-olds also stands out in this regard. Overall 42 percent of this age group recognize the colonial wars in Namibia as genocide (independently of education). Contrary to their young counterparts, this group, however, with two percent shows the lowest rate of rejections to the official government position. A potential explanation would be that the generation of the now over 70-years-old comprises parts of the famous generation of 1968, a highly politicized generation. This generation rebelled against the German political authorities which included many former functionaries of the National Socialist state and against “historical amnesia” in the Federal Republic. Members of this generation are especially aware of the holocaust and thus might be sensitive towards other historical atrocities via a multidirectional memory.9

Higher rates of acknowledgement of the genocide generally translate into higher support for reconciliatory measures. Consequently, we can assume a causal mechanism whereby historical knowledge promotes the recognition of the genocide, which in turn is important for the willingness to support measures for reconciliation. As the two age cohorts of the under 30 and the over 70-years-olds might indicate, historical education on the colonial past and a multidirectional-memory-approach seems essential to boost the acknowledgement of the genocide.

Nevertheless, reparations remain an especially unpopular measure, supported only by 23 percent of Germans. This number rises only marginally to 28 percent among the highly educated, with the majority (42 percent) rejecting it. Amongst the less educated, only a fifth of the respondents (19 percent) support reparations while 43 percent reject it.

The Way Ahead

For decades, coming to terms with both National Socialism and the history of the German Democratic Republic has been part of German culture of remembrance. In particular, coming to terms with the Holocaust and the Second World War have shown that different measures were necessary to rebuild interstate relations, to help heal the trauma of the victims, to develop a new national identity, and to ensure that history does not repeat itself. One important step was the Reparations Agreement between Israel and the Federal Republic in 1952, in which Germany pledged to pay reparations to both the State of Israel and the JCC. Further agreements regulated compensation for victims in other western countries. In 2000, a fund was set up to compensate former forced laborers. These reparations were supplemented by symbolic actions such as Brandt’s kneeling in front of the monument to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the German policy proclaimed by Strauss, which made the survival of the Israeli state a raison d’être. Finally, the Holocaust and National Socialism became an integral part of the school curricula. In addition to textbooks that deal with the topic, there is also a broad memory landscape consisting of permanent memorials and temporary exhibitions.

However, as outlined, the German approach regarding the colonial atrocities committed in Namibia has been limited right from the start. Ultimately, the process flopped because the German electorate still lacks crucial knowledge on Germany’s colonial past and thus does not see the need to deal with it.

Therefore, the future German government should consider the following steps to restart the process:

Firstly, a public debate about the colonial atrocities in Germany is needed. Three of the six major parties represented in the new Bundestag – Christian Democrats, Social Democrats and Greens – have stressed in their election manifestos that the memory of colonialism should be part of the German culture of remembrance. It is time to implement this. The establishment of a joint commission of historians could be a first step towards this goal. Such commissions have been used in the past to promote rapprochement between Germany and France and Germany and Poland, by developing a common view on the past and reviewing historical education in the respective countries. Another approach to stir public debate could be the repurposing of existing monuments and the renaming of streets. Even if local communities, cities or federal states are responsible for such colonial places of remembrance, the federal government could provide the necessary resources to promote information campaigns and, if necessary, to redesign them.

Secondly, funds provided for in the Joint Declaration to promote research and reconciliation projects should be made available promptly and without preconditions. In this way, civil society organizations can start with concrete projects and act as a bridge between both societies. Easing visa requirements might help to foster such an exchange.

Finally, since finding common ground and dealing with the past cannot be imposed by the state, the new German government should start direct and open-ended discussions with representatives of the affected Nama and Ovaherero communities. Such direct talks will take time but can benefit from the measures mentioned above.

Download: Bayer, Markus (2025): Dealing with Germany’s First Genocide: Why Bilateral Negotiations with Namibia Failed and What the New Government Must Do, PRIF Spotlight, 3, Frankfurt/M. DOI: 10.48809/prifspot2503

Download: Bayer, Markus (2025): Dealing with Germany’s First Genocide: Why Bilateral Negotiations with Namibia Failed and What the New Government Must Do, PRIF Spotlight, 3, Frankfurt/M. DOI: 10.48809/prifspot2503

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)

Markus Bayer

Latest posts by Markus Bayer (see all)

- Fading Memories of Hope and Empowerment? Why Remembrance of the Peaceful Revolution in Germany Matters and Needs to be Strengthened - 12. Dezember 2025

- Verblassende Erinnerungen der Hoffnung – Warum das Gedenken an die Friedliche Revolution gestärkt werden muss - 8. Dezember 2025

- Dealing with Germany’s First Genocide: Why Bilateral Negotiations with Namibia Failed and What the New Government Must Do - 26. März 2025