A “Ripe Moment” by Accident? The Turn-Around in Sino-Philippine Relations

In July 2016, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) rejected most of the Chinese claims in the case on disputed “islands” in South China Sea brought to the Court by the Philippines. The verdict triggered widespread fears of a further escalation of the conflict between China and the Philippines as well as the other claimants and the United States. Yet, the near simultaneous ruling by the PCA and the change in Philippine administration from President Benigno Aquino to Rodrigo Duterte created a “ripe moment” for a fundamental transformation of the crumbling Sino-Chinese bilateral relations.

Ripe moments for conflict resolution

As William Zartman, one of the leading conflict researchers worldwide, contends, options for de-escalation or conflict resolution hinge on two core necessary ingredients: first, the chance of finding a compromise position or positive-sum solution and second, the right timing of efforts for resolution.

Put simply, a potential “ripe moment” exists, when all or at least the major parties to a conflict perceive themselves to be stuck in a „mutually hurting stalemate“, that is a situation, where the hitherto preferred, “usually unilateral means of achieving a satisfactory result are blocked,” pain associated with the past course of action increases and further escalation does not promise victory. Pre-mature efforts at conflict resolution are bound to fail.

Yet, on the other hand such a potential ripe moment can pass by unnoticed. It must be actively seized by the conflict-parties to become relevant as a springboard to change. In order to work as a catalyst for change, a ripe moment further requires that both sides perceive a way out. Specific openings that allow for the re-evaluation of the current situation as a mutually hurting stalemate are for example leadership changes or catastrophes that either just occurred ore are deemed impending.

A closer look at the past dynamics of the conflict in the South China Sea shows that such a ripe moment seems to have finally emerged in summer 2016 with the PCA-award after several years of escalating tensions almost by accident.

The way towards the mutually hurting stalemate in Sino-Philippine relations

Serious escalation began in 2012 with a stand-off between Philippine and Chinese ships in Scarborough Shoal, off the western coast of the northernmost Philippine island of Luzon, out of which China emerged victorious. Philippine President Aquino then shifted the Philippine strategy for dealing with its conflict with China away from efforts in conflict management, when he unilaterally and against the expressed wish of China turned to the PCA to establish the legal validity of several Chinese claims. This turn towards conflict-resolution through winning a legal case against China precluded any options for a face-saving solution acceptable to China.

The Aquino government had unwittingly set in motion a process that led to a severe escalation, as China would not budge. In order to coax the Philippines to withdraw its case, China would have had to severely cut down its vast claims in the South China Sea. However, such a retreat would have had severe consequences for China’s further claims in the South China Sea, as well as for its rivalry with the United States over regional leadership. In this situation, China chose not to recognize the court’s jurisdiction and the expected negative ruling. China turned to raising the stakes by establishing artificial islands in the South China Sea. It also provided these with airports, harbors and the means for military defense.

This hardball-response resulted in a deterioration of relations not only between China and the Philippines. Other states with territorial claims in the South China Sea, the Association of South East Asian States (ASEAN), Japan, Australia and the United States sided with the Philippines. Together with further external powers they not only successively increased their political support for, but also broadened their military cooperation with the Philippines. The South China Sea also became a prominent topic for various international organizations, most importantly the G7, who on account of their Foreign Ministers’ meetings in Lübeck and Hiroshima in 2015 and 2016 respectively gave prominence to their common principled position against the Chinese activities in the South China Sea. All of them clearly positioned themselves as supporters of the Philippine turn to international arbitration and made clear that they expected China to respect the ruling. Clearly, the confrontational dynamics brought about an increasingly painful situation for China that also threatened its aim of getting respected as a benign leading power with global aspirations.

For China, the PCA-ruling of July 2016 came as a diplomatic and legal catastrophe, as it all but smashed the Chinese claims in the South China Sea. This came not necessarily as a shock, as it had been anticipated by some time. It nevertheless made obvious that China had arrived at a dead end with ever-mounting costs and low return in exchange.

The Aquino-government focused on the Philippine gains by resorting to arbitration in its evaluation of the situation. However, it also became clear that the Philippine strategy resulted in serious burdens to the Philippines. First, the accompanying deterioration of Sino-Philippine relations had serious consequences with respect to Philippine export. Further, whereas China ventilated a host of lucrative options for other Southeast Asian countries in the context of its Belt and Road initiative, the Philippines were left out in the cold. Worse, these losses were not compensated by enhanced economic opportunities with the traditional trading partners of the Philippines. While the United States, but also Japan, Australia or the EU voiced political support, this did not translate in a significant increase of financial support. Finally, nobody had any idea about how to enforce the ruling without running the risk of military clashes with China. In the event of a military escalation, U.S. support was not guaranteed as the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty is vague on this subject and the United States refused to commit themselves to the military defense of the Philippine claims.

To the new Philippine government lead by Rodrigo Duterte, the Philippines were the big looser in reals terms, even though they won the legal case. In the Words of Philippine Foreign Minister Cayetano:

We were winning the people’s hearts and mind. We were winning the argument of the rule of law. We won the arbitration award. But China was winning the ground war, or they were inhabiting more of the features than we were.

Recognizing the ripe moment and turning towards a way out

Duterte, who was inaugurated two weeks before the PCA ruling on 30 June 2016, provided a way out of this quandary, by putting the PCA-ruling in the backburner. He offered to return to conflict-management along the procedural lines preferred by Beijing: bilateral consultations and negotiations without resorting to the “megaphone diplomacy” of his predecessor in office. His offer has promised to buy time and allows to search for solutions that accept the face-saving needs of both parties.

Duterte’s precondition for restarting the bilateral relations was that China provided the much-needed financial help for a host of large-scale Philippine infrastructure projects, open its market to Philippine exports and show some restraint in the South China Sea. In return, he was willing to reframe China from a bully to a crucial partner for common development

China reacted swiftly, already before the inauguration of Duterte and the impending catastrophe of the PCA-ruling. In June 2016, the Chinese Global times published a roadmap that was to foretell later developments:

The result of the international arbitration filed by the Aquino administration is very likely to favor the Philippines, giving Duterte leverage in bargaining with China. Manila and Beijing might reach a reconciliation: The Philippines will be asked to employ a low-key approach to the result of the arbitration and turn to bilateral negotiation with China; in exchange, China will incorporate the Philippines into its ‘Belt and Road’ initiative, expand investment in the Philippines and seek larger cooperation in infrastructure.

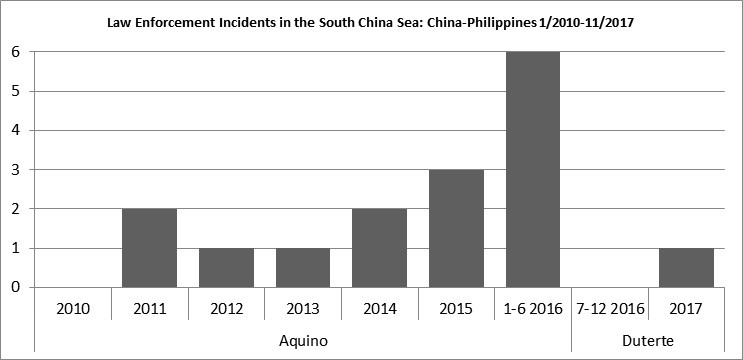

To be sure, the Chinese build-up of military installations on the artificial islands it constructed in 2014 and 2015 in the Spratly Islands still continues unabated. However, in a flurry of bilateral visits, the two sides have not only re-established a dense net of communication, but also achieved significant results with respect to Philippine exports, Chinese financial aid and Chinese tourism to the Philippines. At least as important it is to note that the new dynamics resulted in a dramatic lessening of law enforcement incidents, in which Chinese law enforcement vessels harassed those of the Philippines or other countries.

While it is much too early to tell whether the current honeymoon in Sino-Philippine relations can last, it seems to be a promising beginning that deserves the support of all interested external powers. At the same time Duterte and the external powers should uphold some pressures, as a reminder to China, lest they forget the lessons learned about the experience of a painful stalemate. In the medium term the ongoing process will not survive without some mutually enticing opportunities and it is the task of not only China and the Philippines, but also the most important external actors, to do their utmost to provide the prospects for a more attractive future to provide for such pull factors that over time have to replace the push-factor emanating from the mutually hurting stalemate.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)