Localization of Fatal Police Violence: Evidence from the Philippines

When discussing the use of deadly force in crime control, various factors are commonly considered, ranging from crime levels to organizational culture. Often overlooked is the influence of politics, especially local politics, on police use of deadly force, even though this may provide an important explanation for spatial and temporal variation within states. Using the Philippines as a case study, I contend that local political executives can strongly impact local police use of force levels.1

The Philippines made international headlines for the surge in police killings during the war on drugs proclaimed by Rodrigo Duterte when he became president in July 2016. The following six years saw more than 6,000 suspects killed by the police in law enforcement operations. This underscores that policing can be strongly influenced by political triggers. While overall levels of fatal police violence dropped significantly during the last years, this drop is not without exception. The most prominent is Davao City, the hometown of Rodrigo Duterte, where he had been mayor for most of the time from the late 1980s to 2016.

Davao City: the post-Duterte epicenter of fatal police violence

During Rodrigo Duterte‘s presidency, his daughter Sara Duterte-Carpio served as the mayor of Davao City. Throughout these six years, levels of police violence in the city remained relatively high, resulting in nearly 150 police-related deaths. However, with a rate of 1.4 suspects killed by police per 100,000 residents annually, the violence did not surpass what could be anticipated for a metropolitan area in the southern Philippines during the nationwide war on drugs.

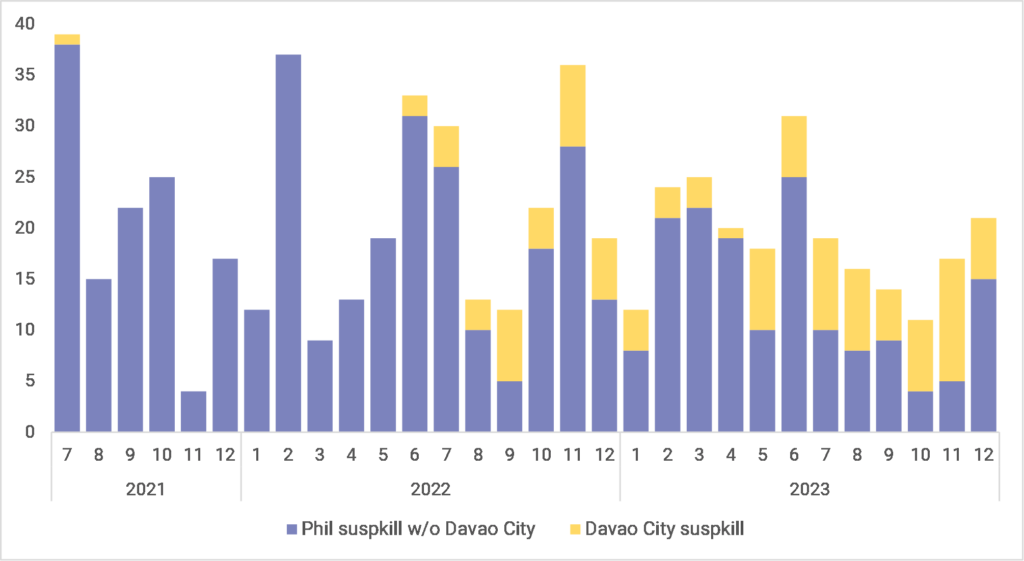

It was only after Ferdinand Marcos assumed the presidency in July 2022 that the use of deadly force by the police surged, jumping from nearly zero in the preceding months to 104 victims over the following 18 months. In 2023 alone, 72 suspects were killed in police operations, almost doubling the number of fatalities compared to the initial and most intense year of the national anti-drug campaign from July 2016 to June 2017, which documented 37 victims. This rise is particularly concerning given that it occurred despite an overall reduction in police use of deadly force, which had largely returned to levels seen before Duterte‘s presidency in the past two years. In 2023, documented cases of police use of deadly force in the Philippines decreased to 228 deaths (Dahas, ACLED,2 and own data). Davao City3 has accounted for over 30 percent of these incidents, despite representing only 1.5 percent of the national population.

This increase in fatal violence cannot be attributed to a national crackdown on crime under President Marcos, nor does it appear to be the result of the actions of the police director of Davao City, who maintained a clean record during his initial four months in office until May 2022. Instead, the dramatic shift coincided with the election of Sebastian Duterte, Rodrigo Duterte’s son, as City mayor, and the return of his father to Davao City.

Already during Rodrigo Duterte’s tenure as mayor of Davao City, the city had gained notoriety for alleged death squad killings ordered by a mayor who employed all means, including extrajudicial methods, to combat crime. This iron-fisted approach was expanded to the national level when Duterte became president.

All available evidence suggests a resurgence of the former mayor’s and president’s (now informal) authority over local law enforcement, coupled with a weak mayor who failed to resist and instead aligned with his father, who had advised him shortly before the 2022 elections:

“If you‘re a mayor, Baste, and you don‘t know how to kill, start now. Study tonight. Because if the mayor doesn‘t kill and is afraid to die, you really have a problem. […] And if drugs come back, I don‘t know what will happen.7

After a local rape case the ex-president fumed in his online-show against the Davao City police: “Look for them. If you cannot find the suspect, then I suggest, look for a rope and you hang yourself in shame. […] Really, I kick your ass in public.”8

The significant increase in police use of deadly force in Davao City, amidst an overall decline in police violence, did not prompt any response from national politics or higher levels of the police hierarchy. Apart from one article by investigative journalists, it also received minimal media attention at the national or local level.

The case of Davao City underscores how local political dynamics can profoundly influence law enforcement practices at the local level. While Duterte’s war on drugs demonstrates how national leaders can drastically alter national law enforcement practices, this case illustrates that local politics can similarly have a significant, albeit localized, impact.

Local phenomena preceding and during the Duterte Presidency

This kind of local exceptionalism is not new to the Philippines. Throughout the country‘s history, there have been instances of local politicians advocating for strong-handed approaches to crime control within their jurisdictions. These figures include mayors who openly endorse vigilante justice through targeted killings of suspected criminals, as demonstrated by Rodrigo Duterte during his extended tenure as mayor of Davao City (1988-1998; 2001-2010, 2013-2016).9 Similar examples include Cebu City mayor, Tomas Osmeña, who advocated a „hunter-squad“10 during a specific period from 2004 to 2006, and Tagum City mayor Rey Uy,11 (1998-2001; 2004-2013; since 2022), who also appears to have authorized a death squad.12 Osmeña famously instructed law enforcers: „if you encounter a crime in progress, don’t be shy. Pull the trigger and I’ll give you a bonus“13 (Osmeña, quoted in Conde 2005), something he repeated in the summer 2016. He succinctly summarized the rationale behind his decision:

“when some of them get killed or blown away, the others (criminals) get out of here. So it relieves me also of that kind of pressure of trying to protect the citizens and I‘m happy if they move out of here”.14

Another notable figure is former police general Alfredo Lim, who, during his tenure as mayor of Manila (1992-1998, 2007-2013), escalated police operations, resulting in at least 55 suspects killed during his term from 2007 to 2010 and 155 deaths during his last term as mayor until 2013. Lim‘s philosophy was

“How can I give protection to the good citizens of this country if I compromise with criminals or adopt a soft-glove treatment? […] The only language these criminals understand is the use of force and violence.”15

His impact is evident when compared to his successor, Joseph Estrada. During Estrada’s first three years until June 2016, only 21 suspects were killed in Manila, representing a reduction of more than 80 percent (own dataset). What unites these local politicians from Duterte to Lim is their uncompromising stance on crime and their readiness to take extreme measures to implement their convictions.

Estrada provides a prime example of opportunistic maneuvering.16 In 2013, he distanced himself from his predecessor by advocating for law enforcement based on rules and an end to the use of deadly force by the police. However, by 2016, the situation had drastically changed. He found himself needing to reconcile with Duterte after having supported Duterte‘s opponent in the elections. In order to do so, he echoed calls to eradicate drug pushers and users, resulting in one of the highest rates of police killings nationwide. During the first and most deadly year of the campaign, 272 suspects were reportedly killed in Manila, more than twice the number in slightly less populous Caloocan and surpassing the figure in Quezon City, which has a population 50 percent larger (ABS-CBN data17 and own dataset).

Similarly opportunistic patterns, with a focus on exchange relations with the national level, can be observed in the years just before Duterte‘s presidency, particularly during Oplan Lambat Sibat, an anti-crime initiative spearheaded by Mar Roxas, who was then the Secretary of the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) and a presidential candidate from the Liberal Party. Under his leadership, „one-time-big-time“ operations and targeted pursuits of drug suspects were widely implemented in several cities and provinces in Luzon. Bulacan province was most affected, with 71 suspects killed by police during those two years, compared to 104 killed in the eight years prior—an increase of over 150 percent (own dataset). Unlike Bulacan, none of the other Central Luzon provinces showed a notable rise in police killings during this period. Although difficult to prove definitively, this alignment with the pet project of a national leader widely perceived to become the next president seems to be linked to Bulacan‘s need for national government support for various infrastructure projects, notably the new international airport planned for the province. Less than a year into Duterte‘s campaign, in May 2017, Bulacan governor Sy-Alvarado offered a striking rationale for the high number of police killings in his province: “while we are creating an atmosphere that is very conducive to business investors, the anti-crime offensive by our policemen has also created an atmosphere not conducive to criminals and lawless elements.”18 By that point, Bulacan police had already killed 228 suspects19 during the 10 months since Duterte took office as President.

In summary, while only a minority of mayors (and governors) actively sought to influence local crime control, such influence has been a consistent aspect of Philippine local politics. Political preferences for a more stringent approach to crime control may stem from the convictions of local mayors, as seen in the cases of Duterte, Uy, Osmeña, or Lim, or may result from opportunistic calculations, as in the cases of Estrada and Sy-Alvarado. Local strategies may take the form of supporting death squads or advocating iron-fisted local policing. The crucial aspect linking local and national level political interference is the lack of institutional insulation of law enforcement institutions against such attempts.

The politics of police use of deadly force

Unraveling the connection between political agency and the use of deadly force by the police presents a complex challenge. Extreme cases, such as that of President Duterte, indicate the significant influence of a determined national chief executive. The situation in the Philippines also suggests that local chief executives can have a substantial impact on the local police‘s use of deadly force in crime control. In both instances, the legal framework and cultural norms of a highly personalized political system converge, empowering politicians to advocate for authoritarian crime control measures, whether driven by conviction or opportunistic motives.

However, the combination of Philippine law and culture grants substantial authority and control over local police to local chief executives, particularly city and municipal mayors. As representatives of the National Police Commission, mayors can select their preferred police director from a shortlist and request transfers. They exercise operational supervision and control over the local police, possess certain disciplinary rights, augment the local PNP budget, and provide addi- tional financial incentives for local police personnel. Leveraging these powers, mayors can either advance or impede the careers of their police directors and impact local patterns of law enforcement.

Therefore, addressing the issue of police use of deadly force in the Philippines may require more than just police reform; it may also necessitate adjustments to the national and local political contexts within which the police operate. One potential approach could involve significantly increasing the police budget to render them financially independent from local government financing. Additionally, it may be prudent to prohibit local government allowances for police officers, thereby insulating the local police from the influence of local government incentives and punishments. Furthermore, strengthening the police‘s vertical chain of command and reducing the powers of governors and mayors over the police in their respective jurisdictions could also be beneficial.

However, these measures alone represent only an initial step. While they may enhance central government control over the police, there are inherent risks, as evidenced by the Duterte presidency, particularly if there is no shift in police allegiance from individuals to principles.

The Revised Philippine National Police Operational Procedures20 serve as a valuable starting point for instigating the much-needed cultural change, as they offer clear and restrictive guidelines on the use of force and firearms. Given the prevailing culture of prioritizing individuals over institutional rules, it will undoubtedly be a challenging task to internalize these principles within the ranks of the Philippine National Police in a manner that safeguards them from undue political interference on both the local and national level. Chances for a behavioral shift should rise with the establishment of an independent police complaints commission with rights to investigation and subpoena.

Download (pdf): Kreuzer, Peter (2024): Localization of Fatal Police Violence. Evidence from the Philippines, PRIF Spotlight 1/2024, Frankfurt/M.

Download (pdf): Kreuzer, Peter (2024): Localization of Fatal Police Violence. Evidence from the Philippines, PRIF Spotlight 1/2024, Frankfurt/M.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)