Elections in the Philippines: A Vote for Continuity?

In a few days, on May 9, 2022, the Philippines will elect the successor of outgoing President Duterte. The most likely candidate to become the new president of the Philippines is Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr, the son of former dictator Ferdinand Marcos. The vice-presidency will most probably go the daughter of the current president, Sara Duterte-Carpio, whose father is responsible for the brutal drug war of recent years. How did this happen, and what does it say about the state of democracy in the Philippines?

The Marcos-Duterte Team Unity: A Strategic Choice for Mutual Success

The hopes of the human rights-oriented international community and Philippine civil society for the May elections rested on the current vice president and political opponent of President Duterte, Maria Leonor “Leni” Robredo. In the Philippines, the president and vice president are elected independently. This provision lay the ground for her easily winning against the president’s partner for vice president at the 2016 polls. Thus, the president was confronted with a deputy of the opposing camp, who could have provided a political counterweight. Yet, Robredo was easily sidelined thanks to the Philippine Constitution, the presidential semi-authoritarian leadership style and the anticipatory submission of the vast majority of Congress to Duterte.

Now, Leni Robredo is running as a candidate for president in the May 2022 elections. She is the face of all those who felt repulsed by the president’s radical statements and policies contemptuous of human rights. However, surveys conducted since October 2021 have shown that while support for Leni Robredo has stagnated at 20%-25% of the vote, the candidates who promise to continue Duterte’s policies have consistently garnered at least 2/3 of all votes. Particularly unprecedented is the dominance of one candidate for president, the son of former dictator Ferdinand Marcos, polling at more than 50% in all surveys conducted by all polling institutes since last November. In all likelihood, Marcos‘ partner Sara Duterte will win the elections for vice-president.

| Oct 21 | Nov 21 | Dec 21 | Feb 22 | Mar 22 | Apr 22 | |

| President: Marcos | 49.3 | 56.7 | 51.9 | 52.3 | 55.1 | 56 |

| Vice President: Duterte-Carpio | 54.4 | 54.8 | 53.5 | 56.5 | 58 |

Poll results of the Marcos Duterte-Carpio tandem (Publicus Asia)

Wishful Thinking and the Weakness of Anti-Duterte Populism

Human rights-oriented groups and parts of the Philippine media hoped that after six years of an excessively violent anti-drug campaigning, Filipinos and Filipinas would now vote by at least a relative majority for Leni Robredo, the representative of the liberal, human rights-oriented Philippines. As with all previous presidents after Marcos, that would be sufficient, as the Philippine electoral system has only one ballot, in which the candidate with the most votes wins the race.

However, initial doubts that Filipinos and Filipinas want a significant change were already beginning to emerge in recent years, when all polls showed approval ratings for the president at 60-80 percent. Even his campaign against drug-related crime found the consistent approval among the vast majority of respondents, despite a flurry of reports of police human rights abuses and initial moves by the International Criminal Court against Duterte. This support translates into close to 90% of Filipinos and Filipinas, who perceived that there is a great deal or fairly much respect for individual human rights in their country in 2019. Visibly, the majority of respondents signals a fundamental interest in continuity for the post-Duterte era rather than clamoring for change.

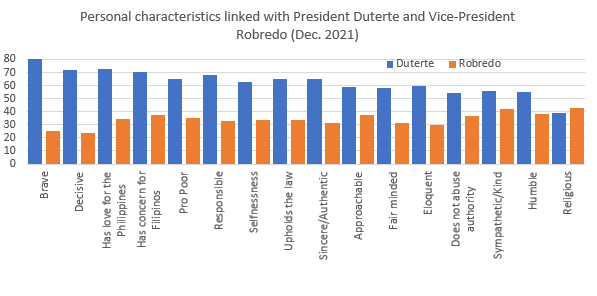

What then are the positive qualities the majority of respondents associate with Duterte? Here, a survey held several times last year on the leadership qualities of the president and vice president helps to establish the attributes valued by the majority and attributed to the president. Qualities range from brave and decisive over responsible, selfless, and fair minded to sincere, humble and religious, and further to upholding the law, exhibiting love for the Philippines and concern for Filipinos. Consistently, Duterte is far ahead of Vice-President Leni Robredo in all aspects except „religious:“ usually by at least 20% to more than 50%.

Unlike Duterte’s critics, most of the population attests success of significant projects such as his economic program and his response to Covid-19. Where scholars speak of „one of the worst-managed responses in the region to the outbreak” of Covid-19, more than 80% of survey respondents back his measures to contain the pandemic and help the population. By far the largest share of survey respondents (42.6%) point to the „Build Build Build“ (BBB) campaign, which got extensive infrastructure projects underway in many regions of the Philippines, as the most “beneficial” project of the Duterte administration. Again, while the majority of the people, the World Bank as well as the Asian Development Bank praise Duterte’s program, saying that „from a historical perspective, the government’s rollout of its BBB program has been incredibly successful,“ his critics claim that it is „the wrong choice of policy from the start.“

In this way, Duterte’s critics create a full-blown enemy image, an artificial opponent exclusively characterized by negative qualities and failures. This imagination is rejected by the vast majority of Filipinos and Filipinas, who see Duterte in a much more differentiated way. Massively exaggerated criticism ultimately damages even those areas where a clear position is necessary, such as the massive human rights violations Duterte can and must be blamed for.

Team Unity: The Promise of Continuity Minus the Excesses of Violence

The same mistake of demonizing the political opponent is found again in the discussion of Ferdinand Marcos. He is reduced to his father’s crimes and the family fortune amassed during the Martial Law years, about which the politically powerful Marcos family refuses to provide any information. Sara Duterte-Carpio is also associated with her father, although no corresponding positions on the use of lethal force against drug-suspects are known from her.

What both have in common is that they would hardly stand a chance to win the elections without their family name, a factor they share with more than half of the post-Marcos presidents: Corazon Aquino (1986-1992), Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo (2001-2010), Benigno Aquino III (2010-2016). Only one purely self-made man made it to the presidency of the Philippines: Joseph Estrada, whose presidency was cut short by a middle- and upper-class coup in 2001. His political persona rested on his past as an actor starring as a good criminal, police officer, and advocate for the little people. While hailing from political families, presidents Ferdinand Ramos (1992-1998) and Rodrigo Duterte (2016-2022) won because of the individual leadership qualities attributed to them. In the case of Duterte this was due to his past record as mayor in Davao City. In public perception, Duterte was an uncompromising fighter against crime who does not shy away from targeted killings. In doing so, he not only pacified “his” city, but made it into the modern flagship of Mindanao.

Marcos Jr. and Duterte-Carpio are an almost ideal tandem bringing many of these dimensions together. Sara Duterte-Carpio exhibits the political persona of a strong-woman, a successful mayor of Davao City, yet, without her father’s rhetorical and real excesses of violence. She has also shown her leadership capacity by successfully forging alliances with a large number of prominent politicians from all parts of the country, while at the same successfully displaying the image of a down-to-earth and pro-poor leader. On the other hand, Ferdinand Marcos Jr. is much more than his father’s son. In this respect, it does little good to paint the picture of the return of a demon, when the new incarnation has held important offices in politics for decades without having attracted much attention. He has been in office since the early 1990s, as a congressman, provincial governor and senator. With his excellent connections and multiple entanglements in a multitude of corruption scandals (which he shares with hundreds of other politicians), he is the ideal-typical „trapo:“ the largely spineless traditional politician oriented toward his own well-being and that of his family, whose core aim seems to be in this case to whitewash his family-name.

Thus, in a sense, the two partners bring in leadership, assertiveness and closeness to the people, as well as family, wealth and connections. And both have made it clear that they will continue Duterte’s general course, with both keeping a low profile on the campaign against drugs. In this sense they clearly link with their voters: 95% of those who want to vote for Marcos believe (and hope) that he will continue Duterte’s policies.

It is not surprising that Team Unity now has the official support of hundreds of politicians at the provincial, city, and municipal levels, regardless of their party affiliation. Over 70 out of 81 governors officially support them. All over the country mayors fell in line “endorsing” Team Unity. All of them pledge to do their best to deliver what is commonly called „command votes“ for the election victory of Team Unity. In general, they are spurring themselves to give the candidates an absolute majority for the first time in post-Marcos history. The governors of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao even promised 70% of the vote.

The Bobotante Voter?

Condescending criticism by media and intellectuals of the Philippine electorate as bobotante (stupid voters) and tanga-suporta (stupid supporters) in need of voter education, of poor voters as “the great unwashed,” who vote against their interests, is cheap and misses two core points:

First, as Kristine Reynaldo notes, Filipinos and Filipinas experience has largely been that: „whoever sits in power, the consequences are much the same for them. Some trapos are just worse than others — so better vote for the trapo they like or have a better chance of receiving help from.“

Second, Team Unity leads amongst all groups irrespective of age, education, social or economic status. If at all, both Marcos and Duterte-Carpio seem to be more a middle-class than a lower-class choice, both are especially popular in the highly urbanized National Capital Region. Thus, both liberal-reformists and left-leaning and human rights focused civil society should do serious soul-searching why they consistently failed to reach a larger number of people for many years.

While fundamental criticism of the Duterte administration and Philippine political practices may be important, it does little good if it is not cast in alternative policies that reach the people in their own language, link with their own problems and perceptions, and can provide convincing alternatives to traditional politics.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)