Impunity and Police Vigilantism – Is the highly excessive use of deadly force by the police in the Philippines now over?

Since June 30, Rodrigo Duterte’s presidency has been a thing of the past. This Spotlight asks why police forces in the Philippines were so willing to carry out the killing of drug personalities at Duterte’s behest in 2016 and what that may mean for the future. I argue that the inability to successfully bring suspects to justice and the resulting damage to the police’s self-image as a potent guardian of peace and order foster vigilante activities by police where a political and social environment exists that legitimizes such a strategy of violent crime control.

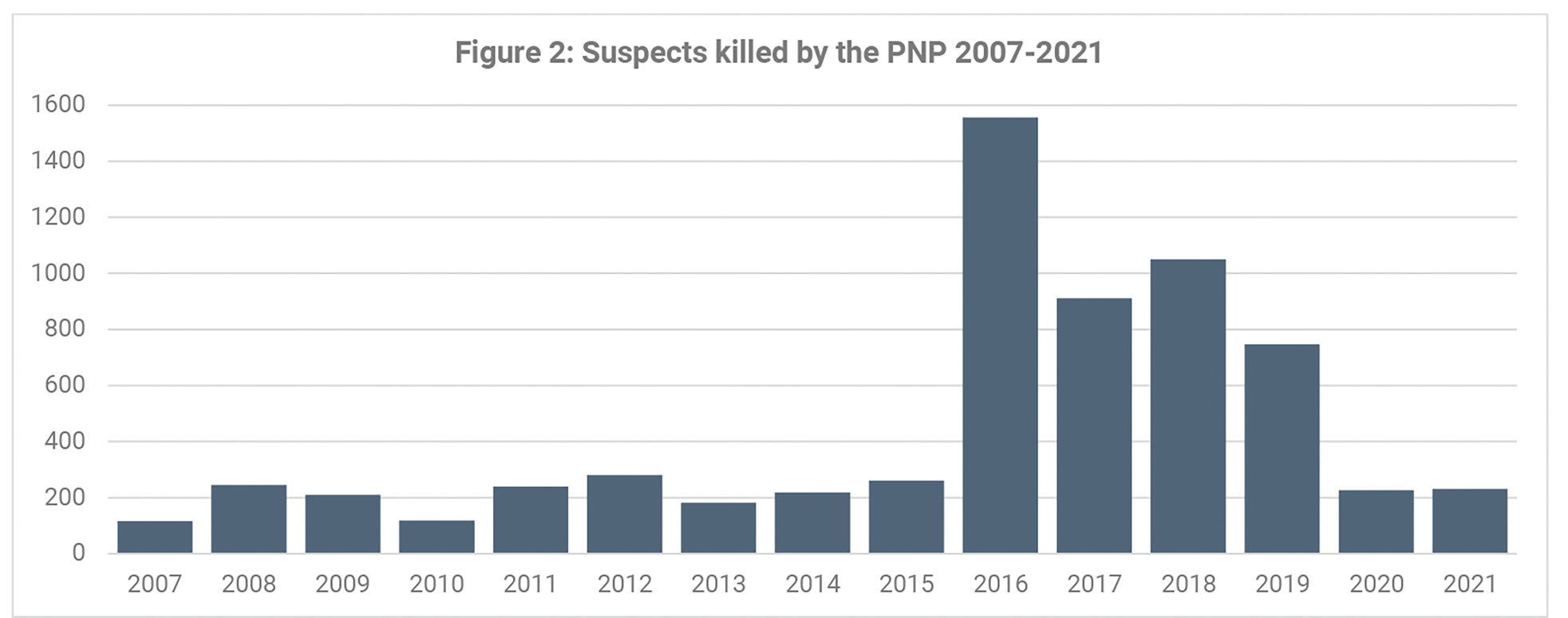

As soon as he took office on June 30, 2016 President Rodrigo Duterte declared war on drugs and issued an informal license to kill suspects to the police. Police use of deadly force in so-called legitimate encounters exploded. In the previous decade, police killed fewer than 200 suspects per year on average.1 However, the first six months of Duterte from July to December 2016 saw 1,500 documented killings by the police. Up to early 2022 more than 6,000 civilians had been killed by the PNP (Philippine National Police) in on-duty “encounters,”2 excluding an unknown number of civilians who died at the hands of death squads and other vigilantes.

How can it be explained that a police force went berserk that hitherto had killed fewer suspects than are killed by the US police after adjusting for population size?3 Why did the police, after getting a simple “green light” from the President, take the law into their own hands and in effect became a vigilante organization by taking on the roles of police, prosecutor, judge and executioner all at the same time?

Police vigilantism: Overcoming frustration by aggression

Failure of the state with respect to law enforcement and the resulting impunity are generally perceived to be important dimensions in the rise of vigilante dynamics in any society. Hardly any attention is paid to the effects of these factors on the police themselves.

Impunity affects police differently from how it impacts the rest of the community, as it signals a “discrepancy between what the police are able to do and what they are expected to do. This discrepancy creates the frustration necessary for police vigilantism.”4 Failure to bring offenders to justice is a direct assault on the professional self-image of the police. Following frustration-aggression theory, “thwarted goals […] may prompt a search for means to address a psychological need and in certain social and cultural contexts, endorsing violence may be a means to that end.”5

Research on vigilantism is generally linked to enforcement of community social control by societal actors who may or may not be linked to the state, such as community vigilantes, civil militias or members of death squads. Participation of the police rests largely on deniability. The police cannot be identified as the perpetrators of violent acts and are therefore unable to take credit for their “success.” Thus, while death squad killings allow for “success,” the police’s own role in this form of extralegal crime control cannot officially be divulged. The damaged self-image cannot be “repaired.”

This is different in cases of on-duty armed encounters. Killing suspects in on-duty armed encounters allows the police to lay claim to the operations while denying their extralegal nature. The police can label the killings as successful crime control and, in this way, mask their vigilante quality as long as they obtain the support of the public and establishment elite for this framing. Framing extralegal killings as self-defense in the context of on-duty armed encounters thus allows the reestablishment of the police as successful guardians of societal peace and order and provides a way out of their inability to successfully fight crime while upholding the rule of law.

Impunity as a stain on the self-image

Impunity has been one core characteristic of the modern Philippines. It holds for all forms of crime, from simple theft to murder and homicide. Before Duterte, the conviction rates for all criminal cases that made it to the court stood at less than 20%. Of the murder, homicide, rape or robbery cases less than 30% made it to court and of these less than 30% resulted in a conviction, meaning that less than 10% of the cases that were reported by the police ultimately led to a conviction. For example, in each year prior to 2016, there were more than 9,000 homicides. Yet, in 2016 only 2,700 made it to court, resulting in 695 convictions.6

While impunity results from multiple failures, the vast majority of cases were already botched by the police because of deficient investigation. This was the concurring assessment of several European police officers, prosecutors and judges working with the Philippine law enforcement agencies for extended periods during the past decade. One police officer, who had worked in 19 different countries and was tasked with devising concepts for enhancement of police investigation in the Philippines, concluded after comparing these cases, “the Philippines rank at the bottom alongside Pakistan and Bangladesh.”7 This overall failure extended to prominent cases of various kinds, from those with international repercussions such as a hostage crisis in which eight tourists from Hong Kong died when the police shot it out with the lone gunman for over 90 minutes, to the unresolved killings of activists and journalists that have regularly made the headlines in the international press in recent decades. It also extends to the approximately 50 to 100 killings of mainstream politicians that occur annually, none of which is resolved in the sense that the principal who ordered the killing is brought to justice. Put simply, recent decades have consistently illustrated that the PNP has, for various reasons, never been able to fulfill its self-image of “Service – Honor – Justice” or being “a highly capable, effective and credible police.”8

“Neutralization” as a badge of success

Before Duterte, the police rarely succeeded in apprehending criminals and gathering sufficient evidence for successful prosecution. Duterte’s tongue-in-cheek advice to kill suspects if they resisted provided an alternative way to proclaim success.

Deficient intelligence was compensated for by requiring local civilian authorities to provide police with lists of drug suspects. This allowed the police to act as an enforcer and “neutralize” suspects under the cloak of impunity. Such action was rewarded in various ways, through “bounties”9 as well as the promise of career advancement and broad societal support.10

As one provincial prosecutor pointed out in an interview, the President’s new line “gave them a great boost in their morale.”11 Framing the deaths as results of necessary self-defense in anti-drug operations allowed the police to present fatalities as examples of success. This resulted in many cases of “competition among station commanders, who is the top notcher for a given week, who had the most [sic] number of cases involving drugs or involving illegal gambling.” The lists of drug personalities became a reservoir of legitimate targets from which to draw for success stories. When it was deemed necessary, the police could kill or arrest without sufficient evidence in the concrete situation: “the police has a good track record and history of that person. […] that person is sure to be into drugs […]. So, the police would take the chance of allowing him to live farther and just maybe put a stop. Sad to say, but it happens.”12

The boost in police morale mentioned above could not have persisted easily had the vast majority of politicians not shifted their allegiance to the President’s camp within a few months after his election. They either refrained from utilizing the means they had available for influencing how the local police implemented the new national policy or publicly supported the President’s drive for political gain. As the above-mentioned prosecutor stated, even though “the governor […], would have a great influence on the conduct or the procedure to be adopted by the local police […] with my nine years in service, I do not recall any warning or any admonition on the part of Governor […], giving a warning to the local police, not to do this and that.”13 Another provincial prosecutor argued: “They have failed in this particular aspect, and it seemed that they just let loose the dogs of war. They didn’t lift a finger. And so, the killings went on.”14

In addition, the public went along with the new violent strategy of crime control. No president before Duterte scored as high in public approval and could sustain public approval ratings at the same level throughout the entire presidency. In addition, his hardline approach to crime enjoyed high and lasting approval ratings among the general population, which clearly favored perceived effectiveness over procedural fairness and the rule of law.15

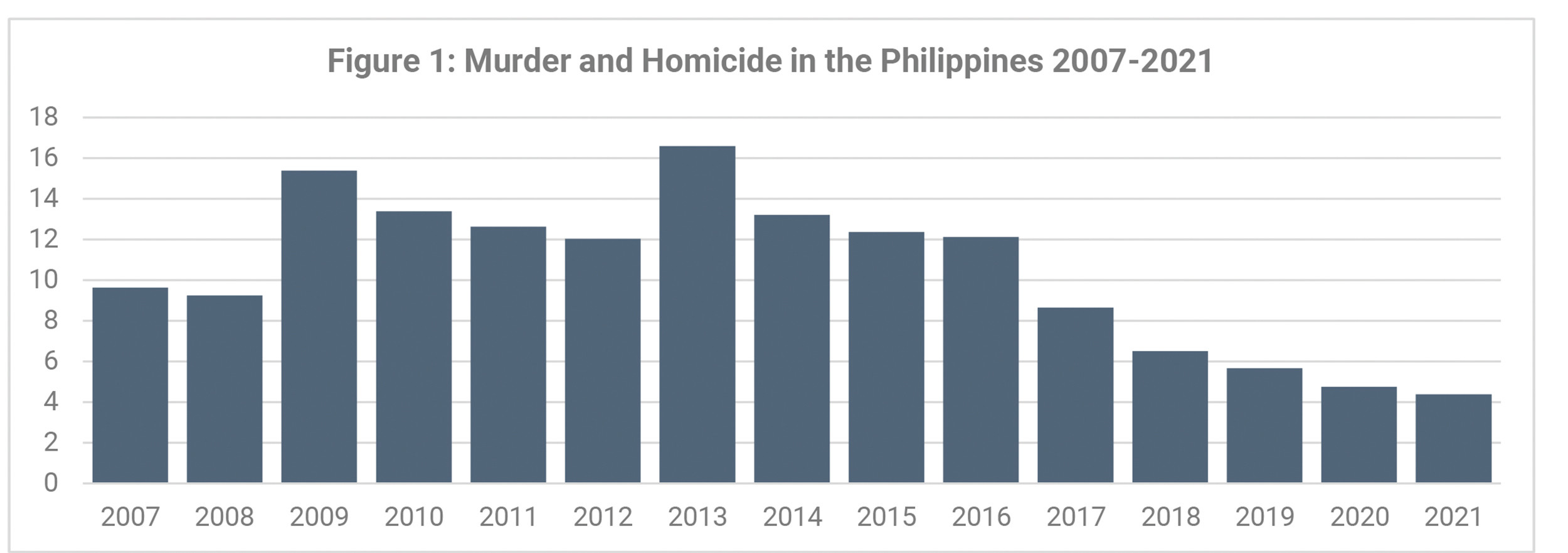

While causality is a complex issue, this perception of an effective police force was bolstered by continual claims by politicians and the PNP that crime was receding to unprecedented low levels under Duterte, a claim that is actually supported by the numbers as shown in Figure 1. Thus, the human costs of the campaign (see Figure 2) are presented as being more than compensated for by the dramatic lowering of civilians victimized by serious crime.16 This self-perception of success was underlined by a 100% pay hike for uniformed personnel that, after years of discussion, was implemented in 2018, providing an external source of increased self-esteem.

Source figure 1: Philippine Statistics Authority. Philippines in Figures, (various years); PNP Directorate for Investigation and Detective Management. Crime Statistics.

Source figure 2: 2007 to June 2016, own dataset; July 2016–2021: ABS-CBN. Map, Charts: The Death toll of the War on Drugs.17

Finally, as Table 1 shows, the efficiency of law enforcement seems to have grown during the past few years, especially concerning drug crimes and categories like rape and violence against women. Cases dealt with in court rose significantly, as did conviction rates, reducing overall impunity and signaling that there were alternatives to police vigilantism.

This improvement coincides, in turn, with a significant drop in the use of deadly force by the PNP, which seems to have reverted almost to pre-Duterte levels since 2020, that is, near or below the longstanding US rate.18

Thus, perceived goal achievement seems to allow for a return to prior patterns of policing. Given recent experience, the new equilibrium will remain fragile as long as the political elite and the general population are willing to tolerate or actively support an iron-fisted crime-control strategy that includes resorting to extralegal practices.

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

| Murder | 25.6 | 24.3 | 29.6 | 33.2 | 34.2 |

| Homicide | 26.8 | 24.8 | 27.9 | 31.7 | 31.3 |

| Dangerous drugs | 27.8 | 32.8 | 78.2 | 83.0 | 83.6 |

| Rape | 18.9 | 25.9 | 30.8 | 24.2 | 37.6 |

| Violence against women | 8.8 | 9.5 | 10.6 | 27.8 | 29.7 |

Table 1: Serious Criminal Case Disposition in Trial Courts 2016-2020: Convicted in % of total disposed cases. Source: Department of Justice. DOJ Open Government Data.

Conclusion

Duterte’s presidency is a thing of the past. It is unrealistic to assume that the massive human rights violations committed by the police in recent years will be addressed in the next few years. At the same time, there is nothing to suggest that the deadly campaign against drugs will be resumed by Duterte‘s successor, Ferdinand Marcos Jr.

As long as extralegal violence is a taboo neither for society nor politicians, police forces whose failures in bringing criminals to justice are diametrically opposed to their self-image as guarantors of internal security are always in danger of using every opportunity, legal or illegal, to be able to report success.

Thus, the next few years must be about strengthening the capacity of law enforcement agencies to successfully contain crime in a legally sound manner and, at the same time, establishing the fundamental norm that illegal orders must not be followed.

Most importantly: police use of highly excessive force was a consequence of the political will of some and the opportunism of many for whom personal gain was more important than the rule of law or human lives. It thrived on broad public support. This indicates the existence of both a need to emphasize the prominent role violence plays in Philippine politics and society as a means of both advancing personal interests and venting anger as well as a complete lack of interest in seriously addressing this issue.

Download (pdf): Kreuzer, Peter: Impunity and Police Vigilantism – Is the highly excessive use of deadly force by the police in the Philippines now over?, PRIF Spotlight 6/2022, Frankfurt/M.

Download (pdf): Kreuzer, Peter: Impunity and Police Vigilantism – Is the highly excessive use of deadly force by the police in the Philippines now over?, PRIF Spotlight 6/2022, Frankfurt/M.

DOI: 10.48809/prifspot2206.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)