Violence in Political Competition in the Philippines: The 2023 Barangay Elections in Perspective

In the Philippines a large number of politicians and candidates are killed before, after and between elections. Against the backdrop of the constants and changes of this violence, I outline why a way out is not in sight and why several dozen dead incumbents and candidates can again be expected in the coming late October elections for Barangay (village municipal ward) leadership position.

Selective focus and wishful thinking

Following elections in the Philippines, a recurring assertion is that they have been “generally peaceful and safe,” despite isolated incidents. While not denying violence, it is consistently downplayed and portrayed as exceptional.

This is possible because official observations and assessments are artificially confined to campaign periods and focus solely on police-confirmed election-related violence. This selective approach greatly distorts the extent of violence linked to democratic competition. Firstly, due to almost complete impunity for political assassination masterminds, the confirmation process conveniently reduces reported cases and victims of election-related violent incidents (ERVI). ERVIs officially decreased from 133 in the 2016 national elections, over 47 in the 2018 barangay elections, and 60 in the 2019 national elections to just 16 ERVIs in the 2022 elections. Completely disregarded is that during these four election-years at least 451 politicians were killed, and injured in, or survived assassination attempts unhurt, and hundreds of politicians were killed in non-election years (own dataset).

It is claimed that measures to reduce competition-related violence are highly effective. The state-run Philippine News Agency, for instance, asserts that “elections in Benguet [province] have always been peaceful,” attributing this success to initiatives like voters‘ education, gender development (GAD), and the signing of integrity pledges or peace covenants, where candidates pledge to uphold the country’s laws, obey election regulations, and act in good faith. However, the absence of political killings in this province cannot simply be attributed to voter education and candidate pledges. These practices are widespread across the Philippines, with each election featuring numerous public highly ritualized political performances where candidates voluntarily promise to follow the law and avoid harming their rivals. With over 100 politicians, on average, becoming victims of assassination attempts during each of the past four election years, it is challenging to argue that these voluntary pledges have effectively deterred violence.

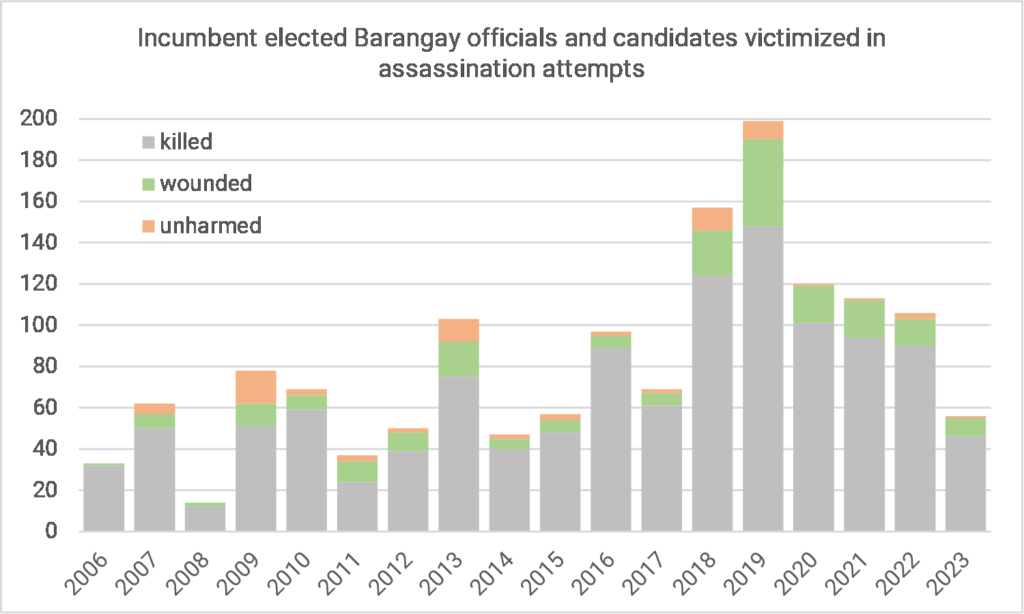

Overall, the author’s dataset records a total of 1497 incumbents and candidates killed, 312 wounded and 147 escaping unhurt from assassination attempts from January 2006 to August 2023. While there may be some underreporting for assassination attempts that left their targets unharmed, the remarkably high “success” rate of 76 percent, as well as police arrests, indicate that those assassinations are the work of professional gunmen.

While this violence is not evenly distributed, and some municipalities, cities and provinces in the Philippines remain violence-free, assassination attempts have occurred throughout the entire country at all times. Considering that almost all of these killings remain unresolved regarding the masterminds, one should refrain from assuming that all are linked to political competition. However, there is sufficient evidence that suggests that the vast majority are.

Assassinating grass-roots politicians

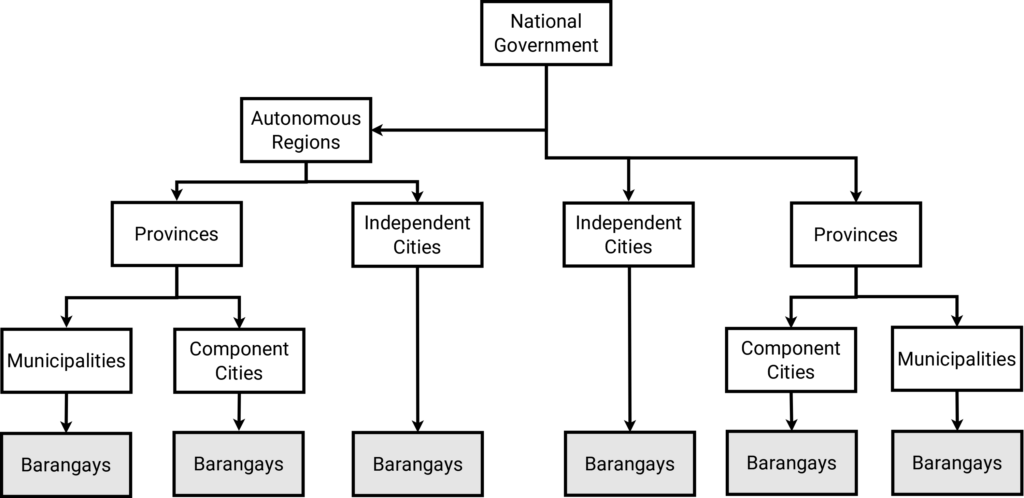

The rate of targeted killings adjusted to elective positions is highest for mayors. However, more than three-quarters of these assassinations are directed at local politicians and candidates at the barangay level, which is the lowest level formal government unit, comparable to a municipal ward or village. Elections for these positions of local leadership, i.e. the barangay chairperson (punong barangay) and seven councilors (barangay kagawad) are set for October 30.

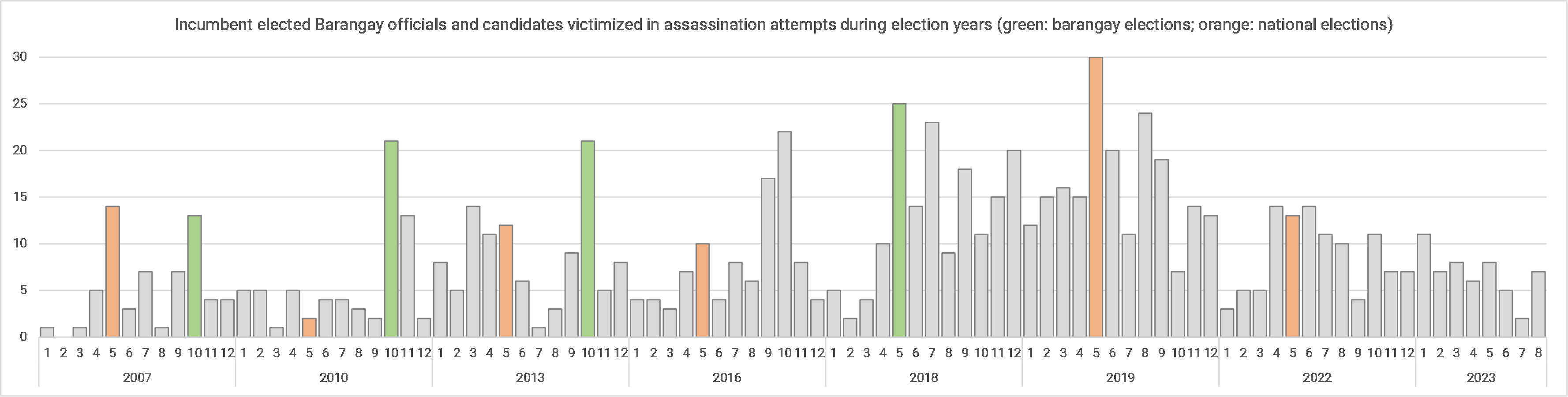

Victims are predominantly incumbents, with new candidates rarely becoming targets. From 2006 to 2022, 605 barangay chairpersons of barangay councils and 503 council members lost their lives. In the ten non-election years since 2006 an average of 28 chairpersons and 22 councilors were assassinated per year. During election years (2007, 2010, 2013, 2016, 2018, 2019, 2022), the average death toll rose to approximately 47 barangay chairpersons and 40 councilors. Clearly, elections matter, nearly doubling the numbers of assassinated grassroots politicians. The wave-like pattern is underlain by a continuous increase in numbers, which escalated dramatically with the holding of the repeatedly postponed 2016 barangay-level elections in May 2018. Subsequent years consistently reported violence-levels surpassing even the peak years of the previous decade.

In earlier elections, there were brief surges in assassinations, shortly before and directly after both national and barangay-level elections, traditionally held, respectively, in May and October of the same year. These dynamics of relatively short-period escalations changed with 2018 barangay elections that had been postponed from 2016. The 2018 elections established a new temporal pattern with less pronounced short-term election-related spikes and comparatively higher levels of assassination attempts independent of the electoral cycle. Thus, the triggering effect of elections seems to have been neutralized, with assassinations becoming more of a permanent feature of grassroots politics.

Strategies against the violence

There are essentially no strategies in place to address political violence targeting office-holders and candidates during the years between elections. However, a spectrum of approaches exists for the election period, starting with the filing of candidacies. These approaches range from integrity pledges and peace pacts, as mentioned earlier, to nationwide gun bans and the establishment of hundreds of police checkpoints during the election period. Additional strategies involve identifying areas of concern and election hotspots, which are then included in election watch lists, leading to the deployment of extra police personnel. Furthermore, the campaign period is reduced to a minimum, typically lasting only two weeks or less.

In certain regions, a contentious strategy is employed, undermining the essence of democratic elections: arranging for only one candidate per position through backroom negotiations among local powers. For example, in a Samar town, 19 out of 20 barangay positions for the 2023 elections have a single candidate, justified as an informal agreement to prevent conflict. In Santo Tomas, Pangasinan, all elective positions in the 10 barangays had only one candidate for more than a decade. Locally, this is said to indicate unity. Similarly, in one Maguindanao del Sur town, all candidates run unopposed in the 2023 elections. In others intense negotiations are ongoing to persuade candidates to withdraw their candidacy before election date. This local practice is perceived as “a way to avert violence in a place where political rivalries could turn violent.” However, such arrangements to prevent competition through backroom negotiations are exceptions to the rule of highly competitive elections.

Law enforcement failure

In the realm of investigating and identifying those accountable for these deaths, the past decades have witnessed a complete breakdown in law-enforcement. Only a handful of extraordinary cases involving high-profile politicians garnered the requisite attention from the political elite. However, even in the majority of these exceptional cases, the masterminds usually evaded detection. While some of the gunmen are apprehended and face legal consequences, impunity for the masterminds remains nearly absolute.

Lack of interest, denial and the perpetuation of impunity

These observations highlight several fundamental issues. Firstly, the significant number of assassinations of politicians outside election periods is entirely overlooked in the public discourse on political violence. Secondly, while the political elite may genuinely express concern about violence against high-ranking political officeholders, they appear to be less concerned about the lives of grassroots politicians. There is also no widespread awareness of the longstanding and nearly complete failure of law enforcement agencies. Both law enforcement officials and politicians seem reluctant to engage in systematic analysis and discussions regarding how to restructure and equip law enforcement agencies to enhance their capabilities for investigation and successful prosecution of such crimes. This is despite the simple fact that successful prosecution is the only way to alter the cost-benefit calculation for potential assassination masterminds. As long as they can easily escape justice, political killings will persist, with the expected costs limited to payments to contract killers.

The 2023 elections – politics as usual, denial and whitewashing?

It is highly likely that we will witness politics as usual both before and after the upcoming elections. Data for 2023 suggest that there will be slightly fewer assassinations in 2023 compared to previous election years.

However, several dozen politicians, candidates and a number of their active supporters and campaign managers will fall victim to violence. The Philippine National Police will assert that most of these fatalities are unlikely to be directly linked to the elections, ultimately concluding that, on the whole, the elections were relatively peacefully. Shortly after the elections, the victims will fade into national obscurity.

The killing of politicians will receive media coverage. In some cases mayors may offer rewards for information leading to the apprehension of the perpetrators. While some of the assailants may face legal consequences, the masterminds will evade punishment, leaving assassination as a viable means of dealing with political rivals.

There will be no systematic endeavor to scrutinize the nearly 100 percent failure rate in police investigations and convictions of masterminds or to formulate reform strategies. In cases involving more prominent victims, politicians are expected to demand swift resolutions from the police and force some reshuffling of local police directors to appear committed. Impunity for those responsible for the killings will persist, enabling them to enjoy the fruits of their actions.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)