For more than a year, the civil war between the Ethiopian government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) has been causing severe human suffering and fatalities in the thousands. According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, both conflict parties have committed serious human rights violations.1 This Spotlight shows how the shifting dynamics of ethnic power relations and the strategy of elite management pursued by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed contributed to the escalation of violence.

Contemporary Ethiopian politics is still largely shaped by the transition from military rule in May 1991, when a coalition of rebel forces, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), deposed the dictatorship of Mengistu Haile Mariam.2 The coalition that took power afterwards consisted of organizations representing four of the major ethnic groups in the country: the Amhara National Democratic Movement (ANDM), the Oromo People’s Democratic Party (OPDO), the Southern Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement (SEPDM),3 and the TPLF. The TPLF was the most important force in the military campaign against the Mengistu regime, and subsequently dominated politics in the ruling EPRDF coalition. Its leader, Meles Zenawi, first became head of the transitional government, then Prime Minister, and was reelected three times, in 2000, 2005 and 2010 until he unexpectedly died in 2012. To balance power between ethnic groups the Meles administration established a system of ethnic federalism (see box “Ethnic Federalism in Ethiopia”).

Ethnic Federalism in Ethiopia

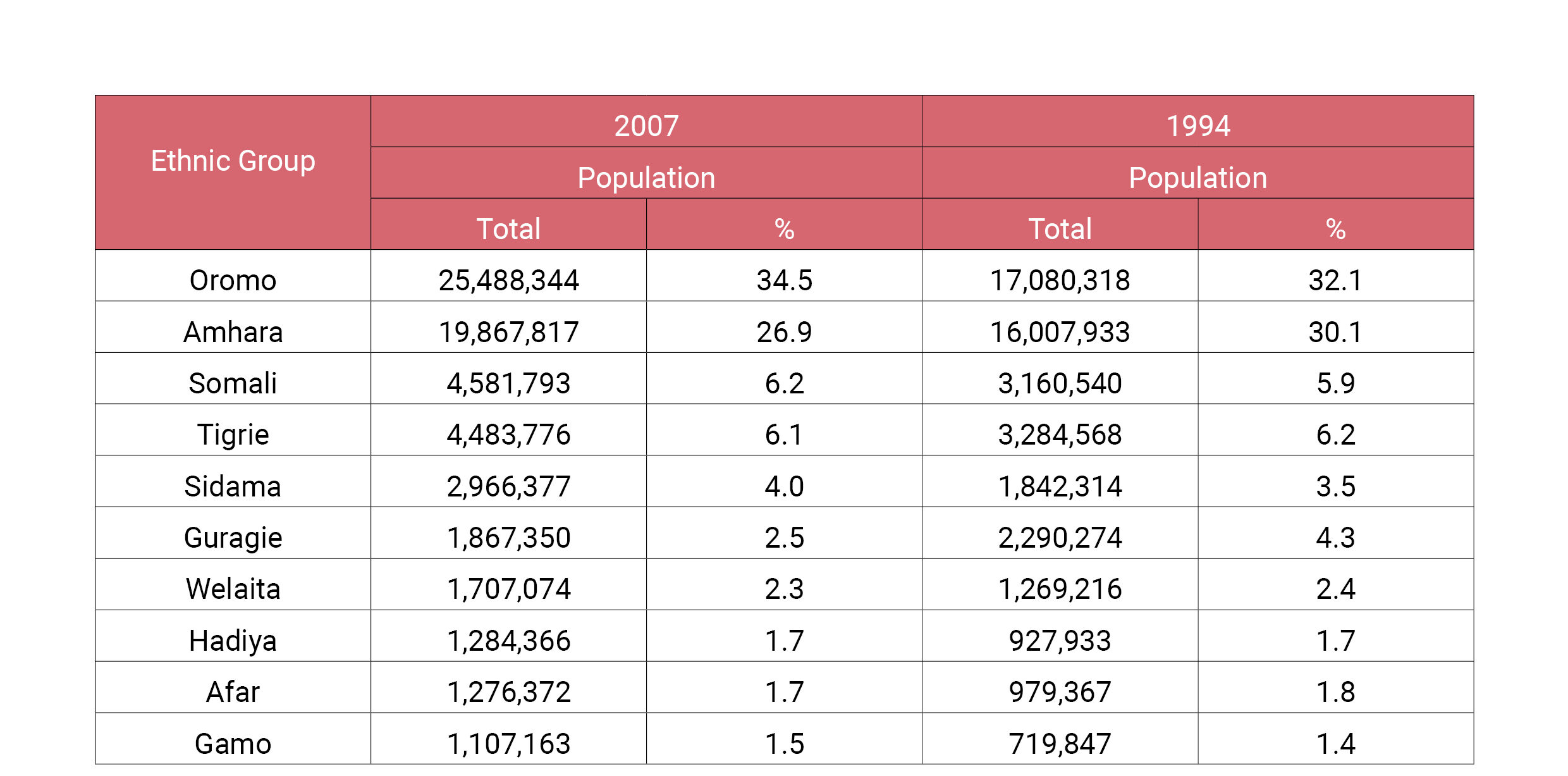

Ethiopia is currently organized as a federation subdivided into eleven regional states and two chartered cities (Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa). Regional states are typically ethno-linguistically based and mostly represent the respective majority ethnic group (see map: Regional states of Ethiopia). The current system of ethnic federalism was implemented through Ethiopia’s constitution, which came into force in August 1995. It provides regional states with self-determination rights, including the right to secession. Regional states hold their own elections and the upper house of Ethiopia’s bicameral parliament has a quota system for including representatives of the regional states.

This post-transition political system under the leadership of the TPLF made considerable economic achievements, but became increasingly authoritarian, by substantially restricting the civic freedoms of Ethiopian citizens. Moreover, the central government essentially monopolized control over revenues and spending of public funds, which deepened the financial dependence of regional governments, effectively impeding their self-determination rights.

Although the general standard of living was increasing, for most Ethiopians there was growing dissatisfaction with the regime because of the perception that state resources and public goods were disproportionally channeled to the Tigray region and TPLF cadres. Tensions further intensified after the death of Meles, and his successor, Hailemariam Desalegn, faced major public protests initiated in 2014 among marginalized people from the Oromia region.

In 2016, the protest movement spread to the Amhara region and eventually citizens across the country demanded an end of repression and corruption by members of the ruling party. Under pressure from the streets, Hailemariam Desalegn announced his resignation at the beginning of 2018. During this process, TPLF lost control of the ruling party coalition and was subsequently not able to install its favorite successor candidate as prime minister. Instead, the other coalition parties cooperated to put Abiy Ahmed, of the Oromo ethnic group, in charge.4

The current civil war in Ethiopia is largely the result of the subsequent power struggle between the Abiy administration and the TPLF.5 After coming to power in April 2018, Abiy Ahmed advanced various reforms and made appeals to national unity. He also realized a peace agreement that settled the conflict between Ethiopia and Eritrea. However, these policies alienated him with TPLF leaders and supporters, who perceived them as a discriminatory campaign against them.

What eventually triggered the outbreak of civil war was disagreement about the general elections initially planned for August 2020. Despite the federal government ordering the cancelation of elections due to the pandemic, the TPLF unilaterally decided to hold regional elections in Tigray in September 2020. In response, the Abiy administration cut state funding for the Tigray region. Accusing TPLF forces of attacking a federal military base in Tigray to steal its weapons, Abiy deployed armed forces to Tigray on November 4, 2020, launching a military campaign against TPLF.

Ethnic Power Relations under Abiy Ahmed

The changes introduced by the Abiy government to the political relations among ethnic groups in Ethiopia, their access to state power and the distribution of resources, were a key factor leading to the outbreak of the civil war. Specifically, three areas were relevant for the escalation of the conflict: (1) the armed forces, (2) the ruling party, and (3) the government.

Being the crucial force in the successful military campaign against Mengistu, the TPLF established a strong dominance within the Ethiopian armed forces afterwards. Subsequentially, TPLF members occupied almost all of the top general positions and most of the broader officer ranks. After coming to power, Abiy moved quickly to reduce TPLF influence in the armed forces. He replaced TPLF generals and security officials with soldiers from other ethnic groups, or with Tigrayans unaffiliated with the TPLF. Some TPLF officials were not only dismissed, but also charged with corruption or human rights abuses, further enraging the TPLF leadership.

The peace agreement with Eritrea, which sparked international enthusiasm for Abiy and won him the Nobel Peace Prize, was negotiated without consulting Tigrayan stakeholders, despite the fact that the conflict was largely fought along the border of Eritrea and Ethiopia’s northern Tigray Region. Indeed, the agreement was only possible because Abiy had previously relieved specific generals and security officials with Tigrayan background who were disliked by the Eritrean government. Correspondingly, TPLF officials denounced the peace agreement with Eritrea as fundamentally flawed and complained about a lack of consultation within the ruling party.6

Regarding party politics, Abiy also shifted power relations to the disadvantage of the TPLF. He initiated the new Prosperity Party to replace the governing EPRDF coalition. The party reform, realized in December 2019, was intended by Abiy to move the country away from ethnic federalism towards national identity. However, a ruling party that speaks for the entire Ethiopian people also signaled the vison of a centralized and unitary state dictating policies to the periphery. This amounts to a complete disempowerment of regional governments, their autonomy and rights of self-determination.

The TPLF refused to join the Prosperity Party as a result, citing the destruction of ethnic federalism as its reason. Downplaying ethnic identity by means of a new national party may have been a crucial miscalculation of Abiy. The TPLF emerged as the vanguard of political and cultural autonomy and as the only available legitimate representation of Tigray people, which greatly enhanced its ability to mobilize for rebellion.7

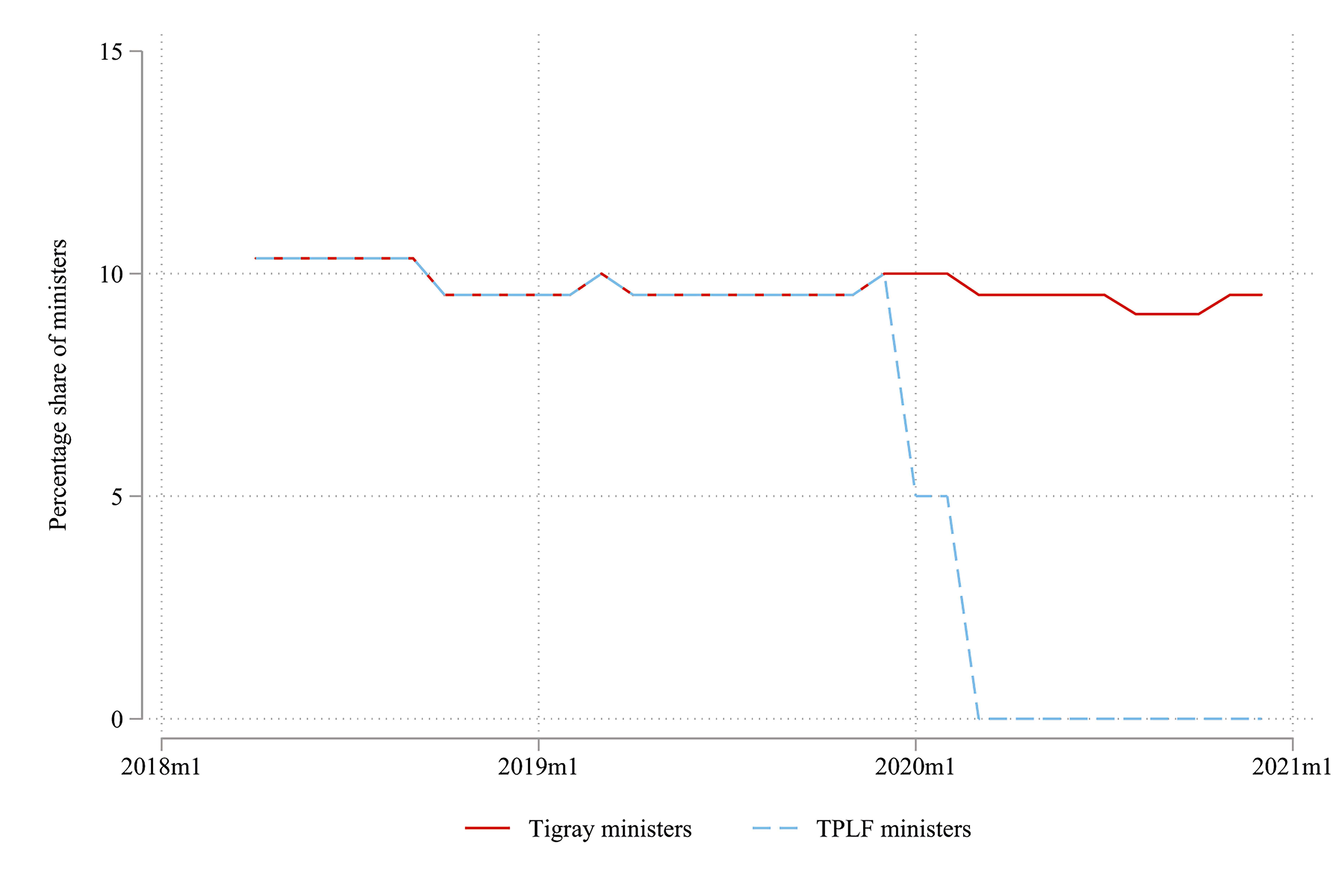

The TPLF was ultimately also excluded from the central government, which was another tipping point in the escalation of the conflict. As shown in Figure 1, Tigrayans were overrepresented in the cabinet of Abiy Ahmed. Although demographically Tigrayans account for 6% of the population, they occupied around 10% of the minister portfolios in the government. However, it is also a misconception that Tigrayans dominated the Ethiopian government. Even under Meles and Hailemariam, they never held more than 12% of the ministries. Figure 1 also highlights that, regarding representation of ethnic groups, Tigrayans did not experience a reduction in their share of portfolios under Abiy even as the conflict escalated. Instead, Abiy was keen to keep the ethnic balancing intact in the government, seeking to separate the question of Tigrayan representation from his systematic demotion and exclusion of TPLF cadres. This became most evident following the dispute around the creation of the Prosperity Party in December 2019. Following TPLF refusal to join the new coalition party, in early 2020 Abiy began replacing TPLF government ministers with independent Tigrayans such as Lia Tadesse and Abraham Belay, a former TPLF member turned critic. The appointment of Lia Tadesse in March 2020 was denounced by TPLF leaders as token representation and her Tigrayan lineage was debated.8

These policies of downgrading TPLF influence pursued by the Abiy administration eventually pushed the TPLF leaders to retreat to Tigray and mobilize for rebellion. With its origins as a victorious insurgent group and decades of dominating Ethiopian politics, TPLF leaders developed a sense of entitlement to state power. While other politically relevant groups perceived Abiy’s policies as leveling the playing field, the TPLF experienced the loss of relative power in the armed forces, ruling party and government as existential threats, and responded with mobilization and eventually violence.

Conclusion

In retrospect, it seems obvious that the Abiy administration, through its strategy of downgrading the TPLF’s access to power in various areas, substantially increased the potential for violent rebellion in the Tigray region. At the same time, this analysis shows the complex and multi-facetted nature of ethnic politics in Ethiopia. It is, therefore, misleading to explain the conflict by only looking at the shifts in the representation of ethnic groups. Instead, the instrumentalization and politicization of the ethnic identity of political representatives appear to be the major mechanisms fueling the escalation of the conflict. The alleged token representation of ministers from Tigray, and the dispute about their lineage that preceded the outbreak of the civil war, substantiate this argument. That is why I would like to call for a more nuanced assessment of ethnic power relations in conflict risk assessment models and explanations of the conflict in Ethiopia.

Regardless of the outcome of the current civil war, whether it will be military victory for either side or a negotiated settlement, the questions of ethnic identity and representation will continue to determine Ethiopian politics and will be crucial in the design of a stable post-conflict political order. Given the limited leverage of external actors, it is up to the conflict parties, and the other relevant political and ethnic groups in Ethiopia to find a stable solution for peaceful coexistence. A revival of ethnic federalism may be a viable option in this regard.