Prospects for Peace in Tigray. An assessment of the peace agreement between the Ethiopian government and the TPLF

On November 2, 2022, the Ethiopian federal government and representatives of the Tigrayan rebels concluded an agreement intended to end the devastating civil war in the region. What some consider to be the world’s deadliest active conflict has caused tens of thousands battle-related fatalities and even more civilian victims due to famine and lack of medical service during the last two years. This Spotlight discusses the prospects of the current peace agreement and potential pitfalls that may undermine its stability.

The current conflict in the Tigray region of Ethiopia, which started in early November 2020, originated from a power struggle between the government under the current President of Ethiopia, Abiy Ahmed, and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). After successfully deposing the military dictatorship of Mengistu Mariam in 1991, alongside other rebel groups and separatist movements, the TPLF became the dominant political force in a multiparty coalition government that ruled Ethiopia for more than 25 years. The coalition under TPLF’s leadership achieved significant economic development for the country but over time grew increasingly authoritarian, with the majority of Ethiopians feeling that the Tigray region and TPLF cadres were receiving an unfair share of state resources in relation to other regions and ethnic groups in the country.

Starting in 2016, major protests against repression and corruption spread across the country, ultimately causing a leadership change and bringing Abiy Ahmed to power in 2018. Abiy introduced various political reforms intended to centralize power and foster national unity that offended TPLF leaders and supporters, who were also increasingly facing prosecution charges for corruption and human rights abuses. In addition, Abiy initiated the new Prosperity Party in 2019 as a replacement for the governing coalition. The TPLF refused to join the Prosperity Party and left the coalition government, retreating to the Tigray region.

The conflict escalated when TPLF leaders proceeded to hold regional elections in Tigray in 2020 despite the federal government’s decision to put a hold on elections due to COVID-19 pandemic. The central government responded by cutting state funds for the Tigray region. After Tigrayan militias had seized control of several army bases in the region in early November 2020, Abiy launched a military operation intended to recover the bases, secure the weapons, and arrest the TPLF leaders, which marks the start of the current war.1

In the years that followed, disputes over the new borders between the two countries eventually escalated into a full-scale war in May 1998, which was largely fought along the northern Tigray border with Eritrea. The war between the two countries was finally brought to an end with the signing of the Algiers Agreement in 2000, although this did not fully resolve the border dispute and low-level fighting continued for years, again primarily in the border region between Tigray and Eritrea. It was Abiy Ahmed who initiated the Eritrea–Ethiopia summit in 2018, which concluded in a joint declaration by him and Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki that ended the conflict and restored diplomatic relations, opening the borders between the two countries again. The peace deal was celebrated across the globe and earned Abiy Ahmed the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019. However, the negotiations and implementation of the deal occurred without the involvement of the TPLF or other representatives from Tigray, sparking protest in the region.

From the very start of the current war between the Ethiopian government and the TPLF in November 2020, Eritrea has been accused of providing military support to the government and launching its own attacks against the TPLF. During the course of the war, Tigrayans repeatedly accused Eritrean forces of committing acts of sexual violence and massacres against the civilian population. However, it took until Spring 2021 for Abiy and Afwerki to confirm the involvement of Eritrean forces in the conflict. Some experts claim that it was the peace talks in 2018 between the two countries that set the stage for a coordinated military strategy against Tigray.2

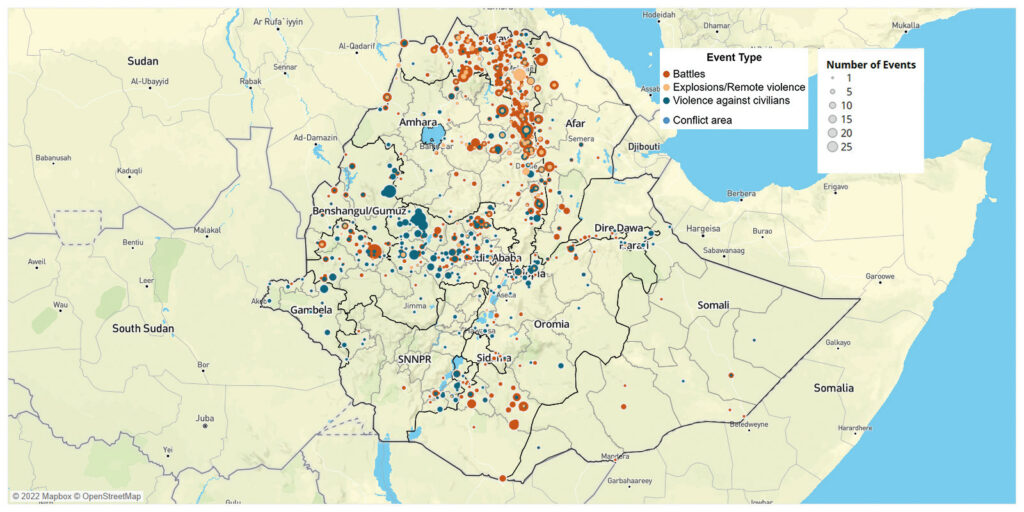

Initially, the military campaign was successful and government forces were able to take Mekelle, the regional capital of Tigray, within weeks. The military operation was aided by coordinated attacks on Tigray by Eritrean troops from the northern border of the region (see box “Eritrean involvement in the Tigray conflict”). Tigrayan rebel troops who had retreated to the mountains, however, succeeded in retaking the capital in June 2021, launching a counteroffensive on Addis Ababa, capturing cities and territory in the Amhara and Afar regions along the way (see map). The Ethiopian government only managed to fend off the attack with the help of a large-scale mobilization of troops and new drones bought from Iran. At the same time, the situation in Tigray had already deteriorated into a humanitarian crisis. Since the beginning of the war, the federal government had blocked access to the region entirely, cutting off food and energy supply as well as telecommunication services, with devastating consequences for the civilian population. From November 2021 to March 2022, the government pursued an offensive to recapture the lost territory, ultimately succeeding in pushing back Tigrayan forces to Tigray. At this point an initial attempt was made to settle the conflict. However, multiple peace talks held between government officials and representatives of Tigray remained inconclusive, with each party accusing the other of breaching the ceasefire. Heavy fighting resumed in August 2022 with battles in the border area connecting Tigray, Amhara, and Afar. The mobilization of additional troops on both sides led to an escalation of the conflict in October 2022, with tens of thousands of casualties on the battlefield until peace talks resumed on October 25, 2022 and a ceasefire agreement was announced on November 2.

The current peace deal

The current peace deal was struck in two rounds of talks between representatives of the Ethiopian government and the TPLF in Pretoria, South Africa, on November 2 and in Nairobi, Kenya on November 12, 2022, respectively. While the first “Cessation of Hostilities Agreement”3 was intended to put a stop to the fighting, the second agreement known as the “Nairobi Declaration”4 reaffirmed the original commitment and laid out further specifics of the peace process. Both rounds of peace talks were convened and mediated by the African Union (AU), largely without involvement of other international organizations such as the UN and the EU, although the United States supported the talks in the background, exerting substantial pressure on both parties to settle the conflict. Taken together, both documents can be considered a first step of a peace process but further negotiations will necessary to achieve sustainable peace. Beyond the cessation of hostilities, the main points of the agreement are as follows.

The agreement states that the Ethiopian government gets to re-establish federal authority over Tigray. It will take full control of the territory along with key infrastructure facilities, such as airports and highways. Additional transitional measures foresee the establishment of an inclusive interim regional administration and federally supervised regional elections, which would, however, be subject to further dialog and negotiation between the parties.

At the same time, the agreement requires Tigrayan rebels to disarm and demobilize their forces, and eventually reintegrate soldiers into the federal army. Disarmament refers to the handover of heavy weapons and light weapons. Here, too, the details are subject to further dialog between both parties’ senior commanders, while “taking into account the security situation on the ground”.

In return for essentially gaining control over Tigray, the federal government is required to restore basic services and provide unhindered humanitarian access to the region. Moreover, some passages in the agreement texts indicate that one of the requirements for the disarmament on the part of the rebel troops is that “foreign” (Eritrean) forces pull out of Tigray.

Prospects and pitfalls of the peace agreement

Peace agreements are inherently a fragile affair, because they seek to reconcile hostile groups in a coordinated process that requires mutual trust and commitment. That being said, one key factor improving the prospects of the current agreement being a success are the relative military capabilities of the main adversaries. Before the conclusion of the agreement, the government side appeared to be in a favorable position, close to achieving a full military victory. The TPLF had retreated to Tigray and was barely able to resist the latest offensive from the Ethiopian government and its Eritrean ally. At the same time the devastating humanitarian situation in Tigray was putting further pressure on the TPLF to cease fighting. Accordingly, the terms of the agreement are strongly favorable to the government side. Research suggests that peace is easier to maintain if a conflict is resolved with one side having a clear military advantage as opposed to situations where the conflict parties possess roughly equal military strength.5 Beyond that, however, the current peace agreement includes two major pitfalls that may undermine its stability.

First, the agreement lacks external oversight. Neither the AU nor any other international organization oversees whether the commitments made by both parties are actually being implemented as intended. Research has shown that external actors can resolve commitment problems by providing guarantees to the conflict parties that both sides will keep their promises. Furthermore, with the presence of third parties, minor breaches of the agreement are less likely to escalate into renewed armed conflict.6

To ensure compliance with the terms of the agreement, the conflict parties agreed on the formation of a Monitoring and Verification Team (MVT) established by the AU. The composition, tasks and, more importantly, the competencies of the MVT, however, are not sufficiently defined in the agreement. The Nairobi Declaration merely states that this “shall be developed in consultation with the Parties [of the conflict]”. Most importantly, the AU has neither the mandate nor the capacities to punish those that break the agreement. This is particularly problematic with regard to the demobilization process, as there is huge uncertainty as regards what will happen to TPLF fighters after demobilization. Given past rhetoric and action by the Ethiopian government, TPLF leaders and soldiers may well anticipate retaliation and punishment, making them hesitant to hand over their weapons. Owing to the unfavorable terms of the agreement for the TPLF, its hardliners may make appeals to continue fighting. As things stand, both sides have already begun to backtrack on their respective commitments. The Ethiopian government is stalling the provision of critical services and humanitarian aid to the Tigray region, while the TPLF is delaying the process of disarmament and demobilization of troops. Thus, the lack of external control has already created a fragile situation where each side has incentives for stalling the process or may consider reengaging in hostilities in order to have a first strike advantage.

Second, there is huge uncertainty about the relevant actors in the peace process. Most importantly, one of the main conflict parties, the Eritrean government, has not signed the agreement. Eritrea may become the main spoiler just because they did not commit to anything specified in the agreement. The agreement text concluded in Nairobi states that the disarmament of Tigray forces is to happen concurrently with the withdrawal of “foreign forces”. However, none of those at the negotiation table controls the Eritrean troops. Accordingly, any unforeseen action by the Eritrean forces could derail the agreement.

In sum, both the lack of external oversight and the exclusion of Eritrea from the agreement undermines its stability. Accordingly, all efforts should focus on how to reduce uncertainty, establish trust, and stabilize the expectations among conflict parties.

Conclusion

Given the problems outlined above, it is of crucial importance that external actors utilize the limited leverage at their disposal to facilitate the conflict parties’ respective commitment to the agreement. The most futile policy options in this regard entail support for the AU monitoring mission along with external incentives and pressure in the form of financial aid and economic sanctions.

Although the AU monitoring mission lacks the mandate to provide strong external oversight, it may very well alleviate commitment problems and reduce information asymmetries by monitoring the situation on the ground closely and encouraging dialog between conflict parties if and when minor disagreements do occur. This all-important role in the peace process would, however, require sufficient staff and financial resources, provided to the AU by external actors such as the EU, the UN, and the US.

Additionally, external actors should use sticks and carrots towards the individual parties of the agreement to foster their commitment to the peace process. This would mean financial aid to help rebuild the regions most affected by the war but also economic sanctions toward the government of Eritrea and Ethiopia in the event that they fail to meet their commitments or undermine the peace process in any way.

If these efforts succeed, the current agreement may provide a promising pathway to peace and may pave the way for a more comprehensive agreement that addresses important issues such as accountability for war crimes and the political future of Tigray within the Ethiopian state. This would in turn also provide a positive impetus for the settlement of other conflicts in the Afar, Amhara, and Oromo regions of Ethiopia (see map).

Download (pdf): Bethke, Felix S. (2022): Prospects for Peace in Tigray. An assessment of the peace agreement between the Ethiopian government and the TPLF, PRIF Spotlight 12/2022, Frankfurt/M, DOI: 10.48809/prifspot2212.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)

Felix Bethke

Latest posts by Felix Bethke (see all)

- Back in Business or Never Out? Military Coups and Political Militarization in Sub-Sahara Africa - 28. Dezember 2023

- Prospects for Peace in Tigray. An assessment of the peace agreement between the Ethiopian government and the TPLF - 16. Dezember 2022

- Civil War in Ethiopia. The Instrumentalization and Politicization of Identity - 23. Dezember 2021