With US-China relations caught in a seemingly inescapable downward spiral and mounting speculation about a new „Cold War“, could a Biden victory in the upcoming US election lead to a reduction in tensions? Based on what is known about Biden’s approach to China, we should not expect a fundamental shift, and the US-China confrontation is likely to shape the international system for years to come. However, a Biden strategy would seek to re-engage allies in Europe, and may offer them a bigger chance to influence this process.

After years of mounting tensions, 2020 saw a further dramatic downturn in US-China relations. While the year was seemingly off to a good start with the signing of a „phase one“ trade deal intended to end the escalating trade war between both countries, this progress was swiftly offset by a series of clashes over responsibility for the coronavirus pandemic, the imposition of a highly restrictive new national security law in Hong Kong, the overseas expansion of Chinese tech companies, and the retaliatory expulsion of journalists. This list is not exhaustive, but summarizes the most serious symptoms of a relationship in freefall. Both sides increasingly see each other mainly as a security threat, creating a self-reinforcing escalatory dynamic.

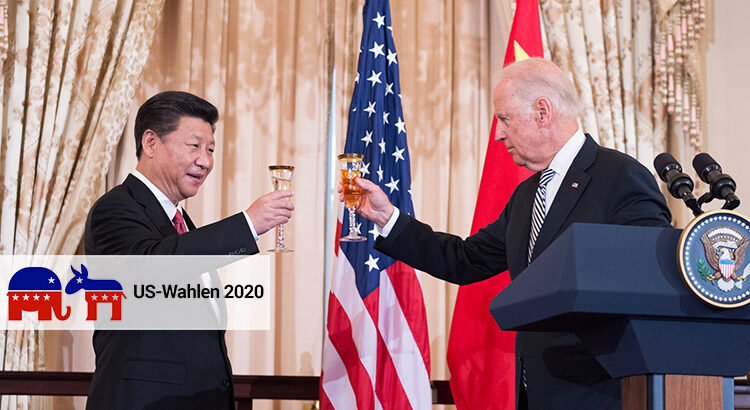

The onset of the US election season has added further fuel to the fire, as president Trump increasingly employed China as a foil to mobilize his base, with even diplomatic venues like the UN serving as little more than campaign backdrops. Meanwhile, his challenger Joe Biden has been seeking to outflank the incumbent with a hawkish stance of his own. In Washington’s highly polarized environment, confronting China has emerged as a rare point of bipartisan agreement. This is not just a question of campaign rhetoric, but also exemplified by a wave of new China-related congressional resolutions, including the outright sanctioning of Chinese officials over the crackdown in Hong Kong. Still, there are important differences in the kinds of China policies that the US would pursue under a second Trump term or a Biden presidency. Since the incumbent’s approach has already been extensively covered, this article will mainly focus on possible shifts that could be expected under the latter.

A Biden strategy on China

Given China’s prominence as a campaign issue, the Biden campaign has issued surprisingly few official policy statements to go on. The most authoritative consists of a few paragraphs in a Biden op-ed on foreign policy, which sketched a dual strategy of „getting tough“ with China on economic and technology issues, while cooperating on global governance issues. The emphasis, however, is very much on the former point, elaborated on further by Biden campaign advisers and former Obama administration officials who would likely occupy key China policy positions in a Biden government. Their writings indicate continuity on several Trump-era elements of China policy, notably the importance of shoring up a domestic manufacturing and innovation base against foreign competition; pursuing a „decoupling“ of both economies especially in security-relevant technologies; operating on the assumption that China will seek to challenge and displace the US-shaped world order rather than slowly adapt to it; and offering robust pushback against Chinese territorial claims over Taiwan and the South China Sea.

The main point of divergence with Trump’s approach is to re-engage American allies among democracies and advanced market economies and build a broader coalition to confront China. This potential has so far been wasted as the Trump administration pursued parallel trade conflicts with virtually all its major partners and did not seek to coordinate with them on China policy. Such a strategy would likely find many takers, as the US is far from the only country or block whose relations with China have rapidly deteriorated in recent years: the EU has been similarly frustrated in the lack of progress on an investment treaty with Beijing; other Western nations like Canada and Australia have become embroiled in spats over issues like the Meng Wanzhou case, arrests of their nationals and Chinese overseas influence operations; and both Japan and South Korea have tense, historically fraught relationships and ongoing territorial conflicts with China.

In a recent survey, large supermajorities in all of these countries held unfavorable opinions of China, ranging from around 70% in Germany and France to over 80% in Australia and Japan. While the coronavirus pandemic is responsible for the latest spike in negative opinion, it has been trending up for years, driven by similar concerns over Chinese trade practices and increasing political authoritarianism. Accordingly, building a coalition is feasible from a policy synchronization angle, and likely to receive robust popular support. If so, this united front would represent more than half of the world’s GDP and China’s external trade, as well as critical supply lines for high-tech industrial inputs.

Whether even such a coalition would succeed in changing Chinese behavior, however, is a different question. A major reason why China’s relations with so many countries have deteriorated is because elites in Beijing have been increasingly unwilling to compromise, based on a belief that China’s rise is unstoppable, and that its political-economic model is the key to this success. Accordingly, the Chinese side is likely to interpret demands for significant reforms as an attempt at stalling its rise, and to offer fierce resistance. The EU’s experience in trying to reach a market access agreement is a case in point: although the looming US election created major diplomatic and propagandistic incentives for China to strike a deal, negotiations are still stalled over its reluctance to compromise on its development strategy.

A Biden approach to China policy would probably drop the incendiary rhetoric characteristic of Trump’s statements on this issue, relaxing tensions a bit. In actual substance, however, it would also expand the areas of disagreement: first, Trump’s idiosyncratic fixation on the trade deficit and Chinese commitments to increase purchases of US goods were actually easier to reach agreement on (if not to actually implement) than questions of market access and technological policy. Second, Trump has focused little on China’s human rights record, considering it a distraction from trade issues, and may at times even have offered private support for some of the most egregious abuses in Xinjiang. Both of these issues have been raised by Biden campaign advisers and would likely receive much greater prominence in a new China strategy, reducing the space for agreements.

A new Cold War between China and the US?

Amidst rising bilateral tensions and China’s rise to peer-competitor status, it is unsurprising that there has been much speculation about a new Cold War on the horizon. This is unlikely, at least if narrowly interpreted as a repeat of worldwide ideological conflict between rigid blocks that have little interaction with each other. The vast majority of third countries have no desire to be folded into such a system, and prefer to maintain robust ties to both the US and China. Between the superpowers themselves, the recent tariffs and attempts to achieve decoupling in technology are concerning, but will still leave bilateral trade and economic interactions at a far higher volume than US-Soviet levels.

However, a Biden victory, the demise of Trump’s „America First“ agenda and a return to Obama-era multilateralism would also draw a much sharper contrast between American and Chinese notions of world order: one guided by universalist principles, the other championing each country’s „right to choose its own development path„; one which seeks to constrain state action through formal rules, the other through morality and relationality; one focused on rebuilding ties among the world’s advanced economies, the other attempting to galvanize support among developing countries. One of the ways in which the Trump presidency has been genuinely transformative is that it has created an opening for China to assume a much larger and more confident role on the global stage, and this is something it will seek to maintain going forward.