At the Age of the Pandemic: The Global Memory of the Holocaust and Armenian Genocide at a Crossroads

Over the last forty years, the Holocaust has become a distinct aspect of Western culture and a universal lesson for protection of minorities and human rights. By contrast, the Armenian genocide is still being denied by Turkey and a culture of commemoration which is lagging far behind. Beyond the reason for differences between memory practices, I argue that a stronger culture of commemoration of the Armenian genocide would have twofold benefits. In the PRIF Report 06/2020, I show how a stronger culture of commemoration is not just a normative expression of the acknowledgement that is a valuable human need for the Armenians, but also would emphasize the universal lesson of the Holocaust – protection of minorities and human rights. In what follows, I will summarize some of the key arguments of the report and present them in the context of the pandemic and other current affairs.

The Holocaust, in which six million European Jews were exterminated as part of what the Nazis called the ‘Final Solution of the Jewish Question’, was perpetrated during World War II. This month (January 27, 2021), the destruction of the six million European Jews will be commemorated in the events of the International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

Over the last forty years, the commemoration of the Holocaust has become a distinct aspect of Western culture, encompassing reparations, museums, memorials, documentaries and even legislation criminalizing its denial. Education about the Holocaust and its continued commemoration is led by, among others, powerful transnational organizations such as the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA), Yad Vashem in Jerusalem and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM).

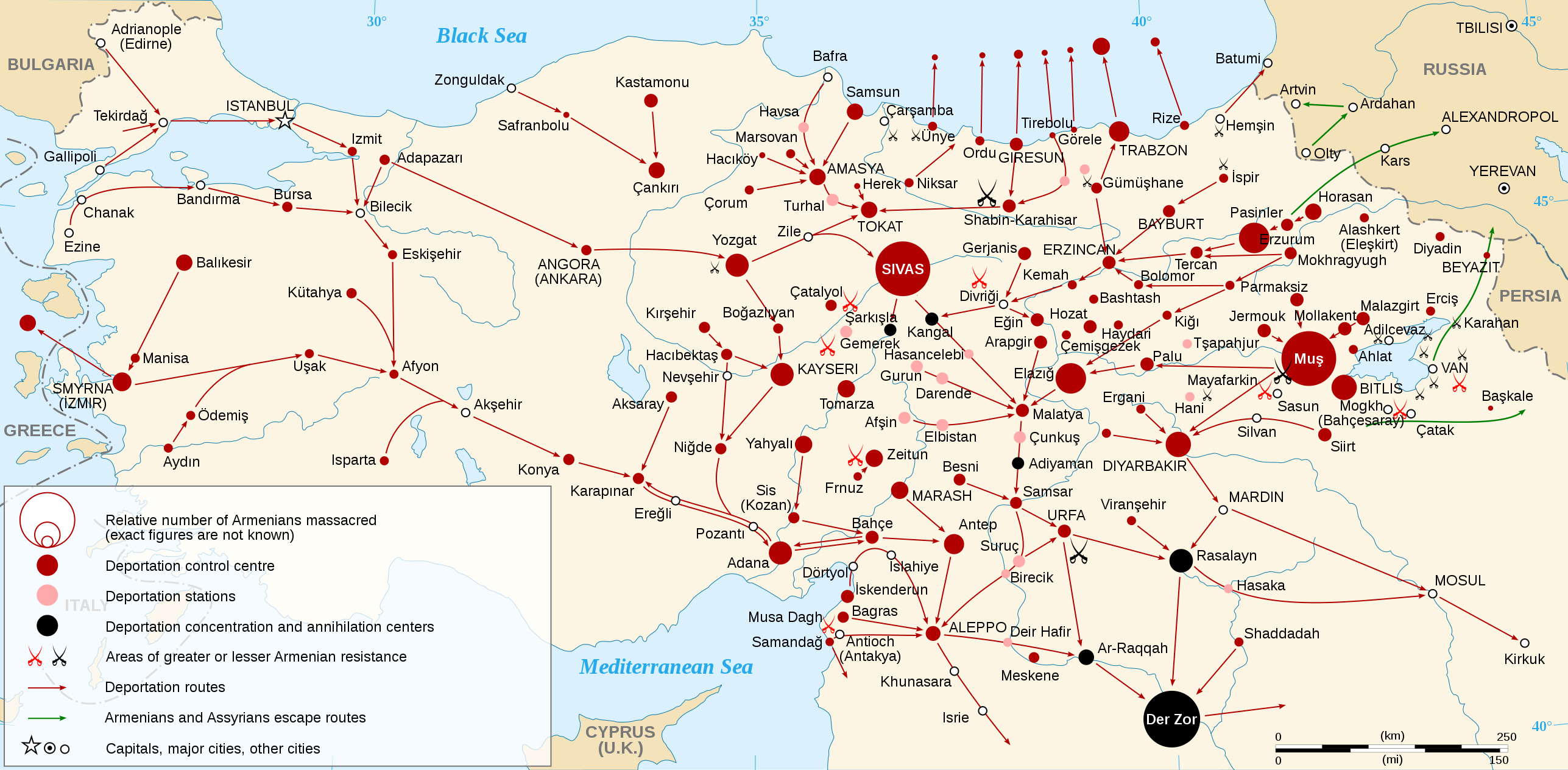

Early in the 20th century, in 1915, during World War I, the declining Ottoman Empire carried out an extended campaign of genocide against Ottoman Armenians. From massacres to death marches, 1.5 million of the Armenian population were exterminated. Since 1923, a formative time for the Republic of Turkey, the 1915 genocide has been denied formally by the Turks.

Only between the years 2016–2019 have parliaments in the US, the Netherlands and Germany recognized the Armenian genocide. Their new stance reflects three main factors: first, the progressive weakening of NATO – specifically, the crumbling relations between Turkey and its three allies named above; second, the process of introspection and eventual acknowledgement of their own role in the perpetuation of Turkey’s denial; and third, that acknowledgment of the Armenian genocide by three NATO allies reflected the growing scrutiny of Erdoğan’s policies, especially toward the Kurds.

Still, the decades of Turkish denial unfolded to a most recent round of violent conflict in the Caucasus region. In September–October 2020 the violent conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, a territory in the Caucasus, re-escalated between Armenia, Azerbaijan and Turkey. This conflict had already emerged in 1988 when the Soviet Union disintegrated at the end of the Cold War. While Soviet Armenia and Azerbaijan fought for their independence, they also developed a border dispute over the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh.

The ghosts of the 1915 genocide keep haunting this conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh. Turkey and Azerbaijan not only share borders but have also become a mutual enemy of the Armenians since the late 1980s. While Turkey has been denying the Armenian genocide in international forums, Azerbaijan, for its own conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, lobbied at any possible forum to support Turkey’s denial. When the most recent round of the conflict flared up in September 2020, Turkey offered unprecedented support to Azerbaijan and supplied arms as well as recruited Syrian jihadists to fight Armenia.

Different Cultures of Remembrances of the Holocaust and the Armenian Genocide

Clearly, the memory cultures of the Holocaust and the Armenian genocide are dynamic and have an impact on the present, and do not only commemorate the past. These memories drive current positions of the perpetrators, victims, and third-party countries. While working on my research project at PRIF about Armenian genocide and Holocaust commemoration in the Cold War, my interest lies in the comparison of the commemoration of Holocaust vs. Armenian genocide, derived from scholarly research that, in many instances, shows how the singularity of the Holocaust implies that recognition of the Armenian genocide would possibly diminish the suffering inflicted on Jewish victims.

The past and the present of both these events provide us with a timely yet historical context to answer the following question: What drives these divergent trends in Holocaust and Armenian genocide memory?

The Global Lesson of the Holocaust

The end of the Cold War and the turn to the unipolar world had an impact on the view of the Holocaust as a global memory that is not only ‘unique’ but also a symbolic lesson on human rights and the protection of minorities.

The first steps towards the ‘internationalization of Holocaust memory’ began with a conference on the Holocaust held in Stockholm in January 2000, attended by representatives of 46 governments. This conference marked the breakthrough in the task of establishing a transnational organization as an international norm of Holocaust education (the International Forum on the Holocaust) and also led to the declaration of January 27 as International Holocaust Remembrance Day (which will be marked this month) – the date which marks the liberation of Auschwitz.

The conference on the Holocaust held in Stockholm concluded that “The Holocaust (Shoah) fundamentally challenged the foundations of civilization. The unprecedented character of the Holocaust will always hold universal meaning”.

More recently, the pandemic crisis provides us with another lens through which to view the differences between Holocaust and Armenian genocide commemoration: International Holocaust Remembrance Day on 27 January 2021 will be commemorated mostly online because of the pandemic crisis. Although the pandemic imposed social-distancing policies, it has boosted the digitalization of Holocaust memory which has been increasing significantly since early 2020.

By contrast, there is no comparable culture of commemoration of the Armenian genocide in Western culture in general and concerning the digitalization of memory culture specifically since the start of the pandemic. In fact, as noted previously, that genocide has been subjected to a vigorous campaign of denial led by the Republic of Turkey and by a marked reluctance of worldwide governments and parliaments to formally recognize its existence.

The Armenians are still lagging far behind with attempts to pass an Armenian genocide bill in parliaments worldwide.

Commemoration as a Zero-sum Game?

One important way to answer the questions posted above would be to consider how the singularity of the Holocaust implies that recognition of the Armenian genocide would possibly diminish the suffering inflicted on Jewish victims.

For example, when the memories of black slavery and European colonialism clash with the memories of the Holocaust in contemporary multicultural societies it drives competitive memory – as a zero-sum struggle over scarce resources.

An example which could help to understand these dynamics even better: Time and time again, when the Armenian genocide bill has come to motion in in the Israeli Parliament, the main concern has been to refrain from compromizing a deeply rooted element of Israeli-Jewish identity associated with the most tragic event in Jewish history: the memory of the Holocaust as ‘unique’. The Israeli Parliament may fear that recognition of the Armenian genocide and marking its annual international commemoration day on April 24, could pave the way for future legislation of a national Memorial Day that could ‘compete’ with Yom HaShoah (the Israeli national day of commemoration) also marked in Israel in late April every year.

Recognition of the Armenian Genocide Emphasizes the Global Lesson of the Holocaust

Recognition of the Armenian genocide would mean emphasizing the global lesson of the Holocaust: that the Holocaust is a symbol of the abuse of minority rights and dehumanization of any religious, ethnic group. Specifically, placing such an emphasis on recognition of the Armenian genocide would also help strengthen international norms such as the UN’s Responsibility to Protect (R2P) and bodies such as the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Ultimately, recognition of the Armenian genocide could also help to reduce competition among victims’ groups in immigrant as well as multicultural societies – specifically the assertion that the Holocaust is ‘unique’ in human history – and to underpin the universal lesson of the Holocaust by affirming protection of minority rights.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)

Eldad Ben Aharon

Latest posts by Eldad Ben Aharon (see all)

- The Politics of Silence in Turkey: The Armenian Genocide on Its 110th Anniversary and a Memory Under Siege - 22. April 2025

- Outlook on German-Israeli Relations: German Staatsraison and Netanyahu‘s Coalition Contentious ‚Judicial Reform‘ - 6. Juli 2023

- Why Israel Backs Azerbaijan in Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: It’s Not About Armenia - 29. März 2023

Download (pdf):

Download (pdf):