Talking Past Each Other? Twenty Years of German-Russian Schlangenbad Talks

The 1990s were marked by high expectations concerning the future of German-Russian or – more generally – Western-Russian relations. With the signing of the NATO-Russia Founding Act in 1997, the Cold War seemed to be definitively over. These developments constituted a positive context for the first meeting of the German-Russian Schlangenbad Talks that took place in 1998. Yet the next twenty years witnessed multiple crises and growing alienation between the two countries. A closer look at the Schlangenbad debates provides a differentiated picture of past discussions, thus allowing for a critical evaluation of the persistent inconsistencies and divergences as a lesson for the future.

The Schlangenbad Talks, jointly organized by the Moscow Office of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung and PRIF, are an annual gathering of high-ranking representatives from German and Russian politics, academia, journalism, business and military. Since its inception in the late 1990s it has served as a reliable trend indicator of the bilateral relations. This post draws on the analysis of all available protocols (1999-2016) conducted on the occasion of the twentieth anniversary Schlangenbad meeting. The full text was published by the Department of Central and Eastern Europe of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

High Hopes and Deep Disappointments: The (Un)Changing Mutual Perceptions

The last two decades of German-Russian debates reveal a story of unfulfilled hopes and growing mutual frustrations, which could best be traced through a recapitulation of the self- and mutual perceptions.

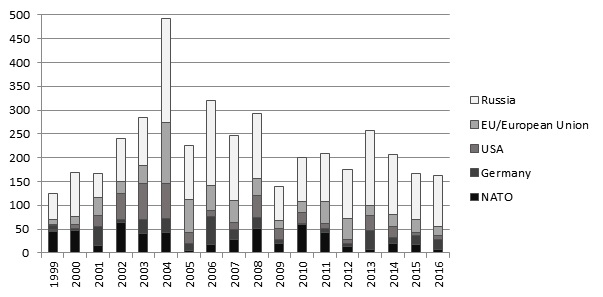

A brief quantitative analysis of the Schlangenbad protocols reveals a striking peculiarity: namely a disproportionate over-concentration on “Russia”, which appeared to eclipse all other themes. Indeed, Russia’s authoritarian drift – which arguably started even before Vladimir Putin came to power in 2000 – became subject to ever intensifying scrutiny on the German side. Despite early warning signals, such as the 2000-2003 NTV case, or the abolition of direct gubernatorial elections in 2004, what appeared to matter more for the German side was the belief that Russia was on its way towards democracy. This delusion cannot solely be attributed to Western naivety or self-righteous arrogance, since this goal was repeatedly confirmed (and is still being episodically reincarnated) in Vladimir Putin’s own rhetoric. Yet the undeniable anti-democratic trend produced growing discomfort over building a strategic partnership with an increasingly authoritarian Russia. One way of overcoming this discomfort involved a deal of wishful thinking – whether based on the willingness to give Russia the benefit of the doubt, or reflecting a true conviction that despite certain drawbacks Russia’s political system was indeed developing in the “right” direction (as laid out in the Charter of Paris). Another approach consisted in outspoken criticism – often voiced (intentionally or unintentionally) in a patronizing manner. Although the German side insisted that such criticism was an integral element of true partnership (a moral duty even), the other side increasingly viewed it as ill-meant hypocrisy, stereotype-induced animosity and an instrument of exerting external pressure. In the early Schlangenbad years, this criticism was mostly met with dismissal. Later Russian participants began stressing the inapplicability of Western political models for the very “specific” Russian case – until Russia’s European orientation has been put into question altogether in the aftermath of the conflict in Ukraine.

At the same time, the impression that Russia and its internal problems enjoyed a disproportionate amount of (mostly negative) attention is not entirely correct – since the sum of references to the cumulative “West” was at least on par with mentions of Russia. It is indeed striking that “Germany” did not seem to be featured as a prominent theme at a conference primarily dedicated to German-Russian relations. However, the diffused focus on the West is not surprising. Throughout the years, German participants were stressing the country’s deep embeddedness in European and transatlantic structures – at times speaking on behalf of the EU or NATO. For the Russian side this often signified an attempt at shamefully hiding one’s own power (or alternatively lack thereof) behind multilateral institutions. The Russian participants themselves did not heed Germany much attention, at times referring to an amorphous collective West: as a homogeneous and unified entity and at other times stressing the inherent lack of common purpose within NATO or disintegrations tendencies within the EU.

The United States, which were featured more prominently in the debates than Germany and the EU, have represented an invisible, but ever present “elephant in the room” during Russian-German debates. On the Russian side, the US was at times used as a sort of lightning rod – for discharging accumulated frustrations about the dysfunctional Western-Russian relations or as a contrast to the allegedly well-functioning German-Russian cooperation. The views of the German side revealed more nuances. Despite episodic criticism of US actions (especially in relation to the 2003 Iraq War) – which the German side did not feel reluctant to voice – the need for partnership and cooperation with the US as well as their role as Europe’s main security guarantor have never been questioned.

Twenty Years of Western-Russian Relations – Twenty Years of Crisis?

The underlying trend toward mutual alienation was reinforced by multiple eruptive crises. The Western intervention in Yugoslavia in 1999, the US-led war in Iraq in 2003, rounds of enlargement of both NATO and the EU, or the Russian military intervention in Georgia in summer 2008: debates on these topics exposed not only the persisting lack of trust between Russia and the West, but also the continuing clash of competing interests. Emotional reactions like proclamations of a “new Cold War” – which can be frequently found in media coverage and other publications these days – have not first started with the Ukraine crisis of 2014. In Schlangenbad they were voiced as early as 1999 when a Russian participant stated that after the Kosovo intervention there could be no return to status quo ante between Russia and the West.

Somewhat surprisingly, years of sharp rhetorical confrontation were often followed by rapprochement and dialogue oriented towards cooperation and mutual understanding. The Schlangenbad debates following the 2008 Russian-Georgian War serve as a striking example: Already at the next conference in 2009 the conflict was all but forgotten and the newly announced US-Russian “reset” was at the center of attention. This quick move from crisis to rapprochement was made possible by the high hopes placed upon the newly elected presidents Dmitri Medvedev and Barack Obama, who were to interrupt the negative trend in US-Russian relations, which had started long before the Russian intervention in Georgia. The normalization of relations between two great powers, one could cynically note, was regarded as more important than a “minor” military confrontation at the outskirts of Europe.

Both Russian and German participants in Schlangenbad also repeatedly attempted to put potential sources of confrontation aside and focus on the positive aspects of relations: shared interests and mutual benefits arising from cooperation. Trade, scientific, cultural and education exchange, energy security and non-proliferation were often cited as fruitful fields of overlapping interests, where practical day-to-day cooperation was expected to function regardless of political and diplomatic troubles. However, identifying common goals and strategies often proved more difficult than expected. Thus, discussions in Schlangenbad about a coordinated strategy to fight the “common enemy” of radical Islamist terrorism in Syria amounted rather to an exchange of mutual accusations than to any feasible results. While the German side repeatedly accused Russia of deliberately attacking the “moderated opposition” in Syria, Russian participants criticized the West for supporting terrorists. These difficulties in finding modes of cooperation even in isolated fields suggest that without a comprehensive discussion about the roots of the conflicts rapprochement could only remain short-term and superficial.

No business as usual, but business that needs to be done

The analysis of the past twenty years of discussions in Schlangenbad has captured the ever-intensifying crises as well as the underlying alienation on both sides. It could be argued that the relations followed a downward trend that eventually culminated in the events in Eastern Ukraine and Crimea in 2014. This time, the long unresolved controversies and conflicting positions could no longer be ignored, sugarcoated by optimistic rhetoric or patched up by new formats and forums of cooperation. For the first time since the end of the Cold War there seems to be no common vision of the future in German-Russian relations. Germany needs Russia at least in certain fields of vital interests, yet opportunities for cooperation are limited by Germany’s normative self-understanding. Meanwhile the Russian political elites and society seem to have lost the consensus on whether Russia is a European country interested in restoring relations with the West.

The twentieth meeting of the Schlangenbad Talks has offered a sobering view on the prospects of relations. In view of the current confrontation, a return to business as usual has been described as not only unlikely, but also undesirable for both sides. In the absence of better alternatives, dialogue is still business that needs to be done.

All available textual protocols (in German and in Russian) can be found on the official website of the Schlangenbad Talks.

Schlangenbad conference reports have been published in Zeitschrift für Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik (in German): 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)

Latest posts by Evgeniya Bakalova (see all)

Latest posts by Vera Rogova (see all)

- Zäsur ohne Konsequenz: Die deutsche Russlandpolitik und das Ende der Ära Merkel - 23. September 2021

- This time, Russia сould not care less - 21. Oktober 2020

- Lost in Transition? Putin’s Strategy for 2024 - 30. Januar 2020