On the brink of escalation: indigenous groups mobilize against the government in Colombia

Since March 2019, indigenous people in the South-Western part of Colombia mobilize. Systematic neglect by the government and security fears have contributed to widespread grievances among marginalized groups in the country, explaining the radicalization of the Minga in the last weeks: It quickly became a broad movement with road blocks at the crucial Panamericana road with more than 20.000 people involved and violent confrontations with security forces. Given the specific setting with social mobilization in the midst of an ongoing conflict with armed groups, the Minga is on the brink of violent escalation. But it also offers a window of opportunity to pressure the government to further reforms.

Colombia is currently experiencing a wave of social movement by different indigenous groups. On 8th March, one of the countries‘ biggest indigenous organizations, the CRIC (Consejo Regional Indigena del Cauca) announced the start of a so-called Minga: As such, the Minga is a traditional instrument largely practiced by the Latin-American native population to find solutions of common concern for the whole community. It has evolved into an instrument of resistance against (neoliberal) social and economic policies of the Colombian government over the courses of the last 20 years, mobilizing sometimes up to 60.000 people. However, it has also proven to be an opportunity to negotiate and agree on policy priorities – which is actually the primary goal of the indigenous groups. The CRIC criticized the government for the lack of implementation of the 2016 peace accord and non-compliance with previous agreements with indigenous people:

„In this Social Minga for the defense of Life, Territory, Democracy, Justice and Peace, we cover the more urgent needs from the country and try to look for solutions to the legitimate demands from diverse social sectors.“ [Original Quote from CRIC, translation by authors]

Stigmatization and radicalization

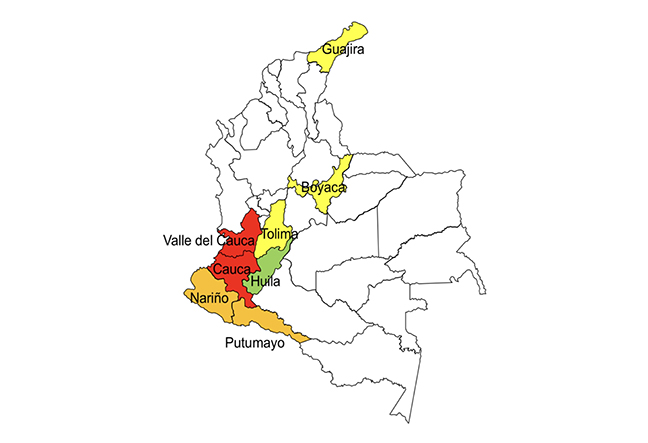

Conservative President Ivan Duque, who took office in August 2018 as fierce opponent of the peace process, initially rejected the invitation of the CRIC to join the Minga, classifying it as illegitimate violent protest. As a result, indigenous groups from other parts of the country have joined the movement, feeling stigmatized and ignored by the government (see map). In order to put pressure on the government, they blocked crucial roads linking the North and the South of Colombia, among them the Panamericana, resulting in considerable economic loss.

Illegal armed groups got involved, spurring violent incidents and leading to accusations from both protesters and the government to have been infiltrated by them. Heavy-handed reactions by security forces combined with stigmatization radicalized the Minga this year. After four weeks of blockade Duque finally traveled to the territory for negotiations on 9th April. Yet both sides could not agree on a meeting space, claiming either respect for security protocols or traditional customs as conditio sine qua non. All indigenous organizations involved have now called for a national strike on 25th April.

In late 2018 similar widespread protests by student organizations were finally calmed down by President Duque’s commitment to increase the planned budget for education. However, the conditions for a quick compromise are somewhat different, for two reasons: Firstly, demands by the indigenous groups are broader and require more substantial efforts by the government. And secondly, Duque made a considerable policy shift in the meantime to a more hard-right stance to please radical wings in his party, the Democratic Center.

Mobilizing grievances and spillover effects

Conditions discussed in social sciences for so-called „mobilizing grievances“ are currently in place: Perceived widespread injustice matches with a high level of unity behind mobilizing structures and a political opportunity. The indigenous groups in Colombia are relatively well organized and are despite different factions and ethnic heterogeneity coherent interest groups that can easily mobilize their communities – even more since basic needs are at stake for them: The respect for their customs with regard to land and compliance with previous laws touches on core identity issues.

Indigenous groups also suffered from the widespread security vacuum after the peace agreement with the FARC and the systematic killings of their leaders. They feel constantly threatened by right-wing paramilitary groups and criminal gangs, unprotected by the government. The demands of the indigenous groups are thus far-reaching, ranging from better protection to decision-making rights regarding the use of their territory, respect for their cultural autonomy up to the fulfillment of compromises of the Peace Agreements. They touch on deep rooted grievances and thus resonate widely in the territories outside the major cities.

Their mobilization thus quickly had spillover effects to other marginalized social groups, most importantly afro-Colombian communities and peasants. Other actors declared solidarity – for example student organizations, departments of anthropology of all Colombian Universities and more than 30 parliamentarians openly rallied behind the indigenous demands. A petition to the president was signed by more than 1.200 social organizations.

Duque’s position: A fragile mixture of isolation and securitization

The political power position of the president himself reflects a fragile mixture of increased radicalization and isolation. On the one hand, Duque has positioned himself now in the far-right, bowing in to radical wings of his party. He has systematically slowed down the implementation of the peace agreement right from taking office in August 2018 up to openly rejecting core elements of it. In addition, public order has been further securitized, by a higher intensity of violent confrontations between non-state state armed groups and the state. Illegal armed actors are still widely present in South-Western Colombia and have not only attacked social leaders directly. They may hijack the Minga to attack the state security forces – and vice versa.

On the other hand, Duque’s policy shift has further isolated him: In parliament, a coalition of more moderate forces recently formed a voting coalition in favor of some contested elements of the peace agreement and openly opposed Duque’s position with a huge majority. His approval ratings among the general population are considerably low [see the 2018 PRIF Spotlight on Colombia Under the Duque Government].

Escalation or Agreement?

Confrontation and radicalization make escalation a realistic scenario. The failed meeting on April 9th reflects not only irreconcilable positions on both sides in the substance but significant contestation with regard to the organizational terms of further dialogue, further shrinking the space for negotiations. Even though it is not clear how broad popular support really is given the fact that Colombia is a country with strong social and economic cleavages, the indigenous groups can count on considerable backing and have not much to lose, as this statement from CRIC from 10th April clearly signals:

„We are going back to our territories, we are going to hold a directive meeting, afterwards we will come back in a new mobilization much bigger than this one […]“ (translation by authors).

Moreover, the perception is widely shared among vulnerable and marginalized groups that the government’s intention is to pay lip service and to portray itself as conciliatory in the media without an interest to reach substantial compromise. Duque has travelled to the regions to meet with local authorities and entrepreneurs to mitigate the economic effects of the blockade, framing the mobilization in line with this as anti-progressive:

„These days, when many speak about striking (parar, also ’stop‘ in Spanish), I want to tell that Colombia does not stop; we do not stop dreaming of a better country, do not stop dreaming of more investment, do not stop dreaming of more entrepreneurs. Do not let anything or anybody take away from us the optimism and lead us into the road of polarization that ruined other countries in the continent…“[1].

Yet: despite the confrontational stance on both sides, a window of opportunity for agreement still exists. Duque is in need of political support in order to secure his political survival and his own political goals. Indigenous groups, social organizations and opposition parties might thus create a winning coalition to force Duque into political commitments – a more positive though less realistic scenario.

[1] Original tweet: „En estos días, cuando muchos hablan de parar, quiero decirles que Colombia no para; no paremos de soñar con un mejor país, no paremos de soñar con más inversión, no paremos de soñar con más emprendedores, no dejemos que nada y nadie nos arrebate el optimismo y nos quiera conducir por el camino de la polarización que arruinó a otros países del continente … „Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)

Latest posts by Solveig Richter (see all)

- USAID Facing its End? Likely Consequences for International Democracy Promotion - 7. Februar 2025

- A punto de escalar: grupos indígenas se movilizan en contra del gobierno en Colombia - 18. April 2019

- On the brink of escalation: indigenous groups mobilize against the government in Colombia - 17. April 2019

Johana Botia Diaz