Foodies of the World Unite: World Food Day Reminds us to Politicize Nutrition

16 October is World Food Day. This year, spotlights are guaranteed because the United Nations World Food Program just received the 2020 Nobel Peace Prize. Despite these high levels of attention on food, the political and economic structures driving global production and consumption habits remain in the dark. Food has become a heavily individualized aspect of life. But who likes to eat alone?

The Nobel Peace Prize has at least two possible functions. Usually, it honors someone’s achievements for world peace. But it can also generate attention for a specific topic and thereby contribute to potential achievements in the future. No offense to the work of the honored organization, but this year’s prize is almost certainly of the latter category. The United Nations World Food Program (WFP) is the largest humanitarian organization combatting hunger. In 2019, it provided aid to almost 100 million people in 88 countries. And although it certainly has worthy achievements in its portfolio, these numbers are in themselves an indicator for the failure of providing enough food for everyone. The Millennium Development Goals had already proclaimed to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger. But when they expired in 2015, this goal was far from achieved and needed to be converted into Goal 2 of the new Sustainable Development Goals (“Zero Hunger”). And still, as the UN admits: “The world is not on track to achieve Zero Hunger by 2030. If recent trends continue, the number of people affected by hunger would surpass 840 million by 2030.”

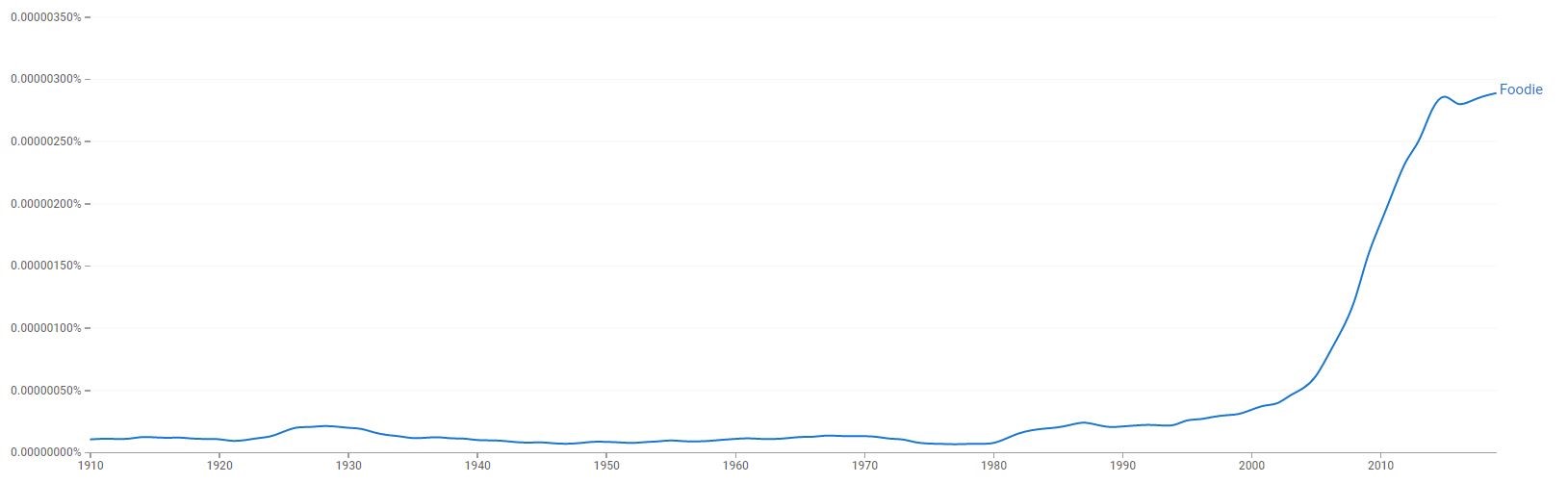

World Food Day is another occasion to highlight this failure. It is observed every year on 16 October in remembrance of the day when the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) of the United Nations was founded in 1945. The FAO is responsible for the policies and the knowledge required to achieve a world without hunger. The WFP was founded much later in 1961 in order to respond to humanitarian emergencies and to deal with concrete food shortages on the ground. In a sense, the need for establishing the WFP shows that the FAO was not successful in delivering on its mandate. World Food Day raises awareness to these issues around food. But have you been online recently? It seems hardly necessary to focus more on food in a world in which the minds of people are preoccupied with nothing but its celebration. Social media has fueled a trend that has since then been dominating the internet from YouTube to Instagram to the New York Times’ popular food reporting: the rise of the foodie. A google n-gram analysis shows that the term „foodie“ has exploded after the millennium, making a special day to raise awareness on food seem superfluous.

Two forms of Individualization

According to Wikipedia, a foodie is a person who has an ardent or refined interest in food and who eats food not only out of hunger but due to their interest or hobby and is passionate about food. However, this passion is couched in a highly individualized framework of stylized class representation and self-distinction which lack the intellectual connection of enthused consumers with the economic structure in which their food is being produced, transported and sold. In other words: in their love for food, many foodies remain highly individualistic and ignorant with regard to how their consumption habits impact those individuals who would like to eat food not only due to their interest or hobby but because they are actually hungry.

However, there is a problem even for those consumers who reflect on their habits and actively try to contribute to more equitable food systems by consuming sustainably: it is by far not enough. Despite the huge rise in ecological and organic markets during the last years, the share of organically produced food in Germany, for instance, is still below 5%. And even these organic fruits and vegetables are often produced in circumstances that undermine the human and labor rights of agricultural workers, their production needs far too much water, and they are being transported in unsustainable ways that have a direct impact on the hunger crises in places elsewhere. Although the agricultural and supermarket industry has been promoting an individualized lifestyle of ethical choice which makes some people feel good about their diet (and which certainly has positive impacts on their health and the environment), relegating the responsibility for food systems to the consumer means to outsource it to the weakest part of the chain. This is not only ineffective but reinforces class distinctions and leads to further individualization. People with low wages feel like sustainable food is an unaffordable luxury. At the same time, the ecologically minded upper-class frowns upon the unethical consumer choices of others.

As I have argued elsewhere, the current crisis of hunger, malnutrition and unequal access to food is centrally a crisis of food production, not only consumption. The globalized food system is so complex that it would need a proper form of governance that manages to reconnect food, environment, and human rights, and especially one that covers food from a holistic perspective; i.e. from the aspect of land access and ownership, to seeds and their patents, to the working conditions of agricultural workers, to the sustainability of pesticides, to questions of transport, fair prices, subsidies, distribution and access to food. Therefore, it is welcome that the FAO has chosen the holistic motto “Grow, Nourish, Sustain. Together” for this year’s World Food Day. The keyword “together” is decisive in this context, because no national agency (not to speak of a single consumer) would be able to even trace and understand the supply chains in food, and how they could be regulated. This became apparent during the first weeks of the Covid-19 crisis when supermarkets struggled to meet the rising demand and rationed key products such as vegetables, while, at the same time, farmers were forced to destroy a year’s harvest of vegetables or dump millions of liters of milk because the closure of public institutions curbed demand and caused prices to plummet. Even nationally, most countries have no overarching institution for coordinating food supply chains and showcased a sincere lack of expertise on how to quickly direct the produce to places that need it.

Politicizing Food

Unfortunately, the FAO quickly falls back behind its own slogan when it celebrates World Food Day by designating “food heroes”, individuals who have good ideas on how to waste less food or support communities in need. It seems almost ironic that the UN agency supposedly governing food and agriculture at a global level has nothing to offer but a few individual success stories, matching the isolated foodie with isolated innovators in the field. Yet, the FAO is left with almost no choice.

With an annual budget of $ 2.6 billion (the German medium-sized city Frankfurt am Main has almost double the budget), the FAO is an International Organization starving for authority. With the rights and means delegated to it, the FAO is not capable of actively steering the world market on food. Similarly, the Nobel Peace Prize Laureate WFP goes on a begging tour every year and often fails to acquire even the minimum amount necessary to fulfill its obligations. This is a conscious choice by the governments of member states who decide on an annual basis that people dying of hunger is fine. In frustration, many rural social movements in the global South have changed course and, instead of hoping for a global redistributive mechanism, have started advocating food sovereignty which has protectionist or localist tendencies. More importantly, however, food sovereignty is a quest for politicizing food production and distribution. In contrast to the older concept of food security, it takes food out of the technical realm and highlights that hunger and malnutrition will only be overcome by changing the global supply chains, by getting rid of European food subsidies and by reappraising how the politics of food shall be organized.

These discussions are ongoing. It is commendable that the Nobel Peace Prize and the World Food Day raise awareness for the issue of food. Yet, the necessary changes will only come from a de-individualized, political approach to food. Foodies can keep loving buffalo mozzarella, but they should collectively demand a system in which it is produced, shipped and sold in a way that does not diminish other people’s chances of enjoying food, too. There are ways to do that. In the German context, for instance, there have been a number of demonstrations declaring that “we are fed up” („Wir haben es satt“). You can support your local La Via Campesina chapter, or join FIAN. Or you can start by educating yourself on the international dimension of the agricultural crisis by registering to this webinar series. Because eating together is more fun and struggling for food together is more effective.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)

Felix Anderl

Latest posts by Felix Anderl (see all)

- Why will so many Scientists Boycott the UN Food Systems Summit? - 16. Juni 2021

- Bäuer*innenproteste in Indien und anderswo: Der Aufstand des Landes - 17. Februar 2021

- Foodies of the World Unite: World Food Day Reminds us to Politicize Nutrition - 16. Oktober 2020