Arms Transfers in the Gulf of Aden. Shining the Spotlight on Regional Dynamics

Since the outbreak of the war in Yemen in 2015, the state has seen a growing influx in the supply of weapons. These weapons are both legally and illegally provided by regional and international powers to all major factions of the conflict. While arms transfers and their effects on the conflict in Yemen have received considerable attention, a lesser known fact is that weapons are increasingly circulating between Yemen, Somalia and Djibouti – the three states adjoining the Gulf of Aden. Against this background, this text shines the spotlight on weapons flows dynamics in a highly militarized region.

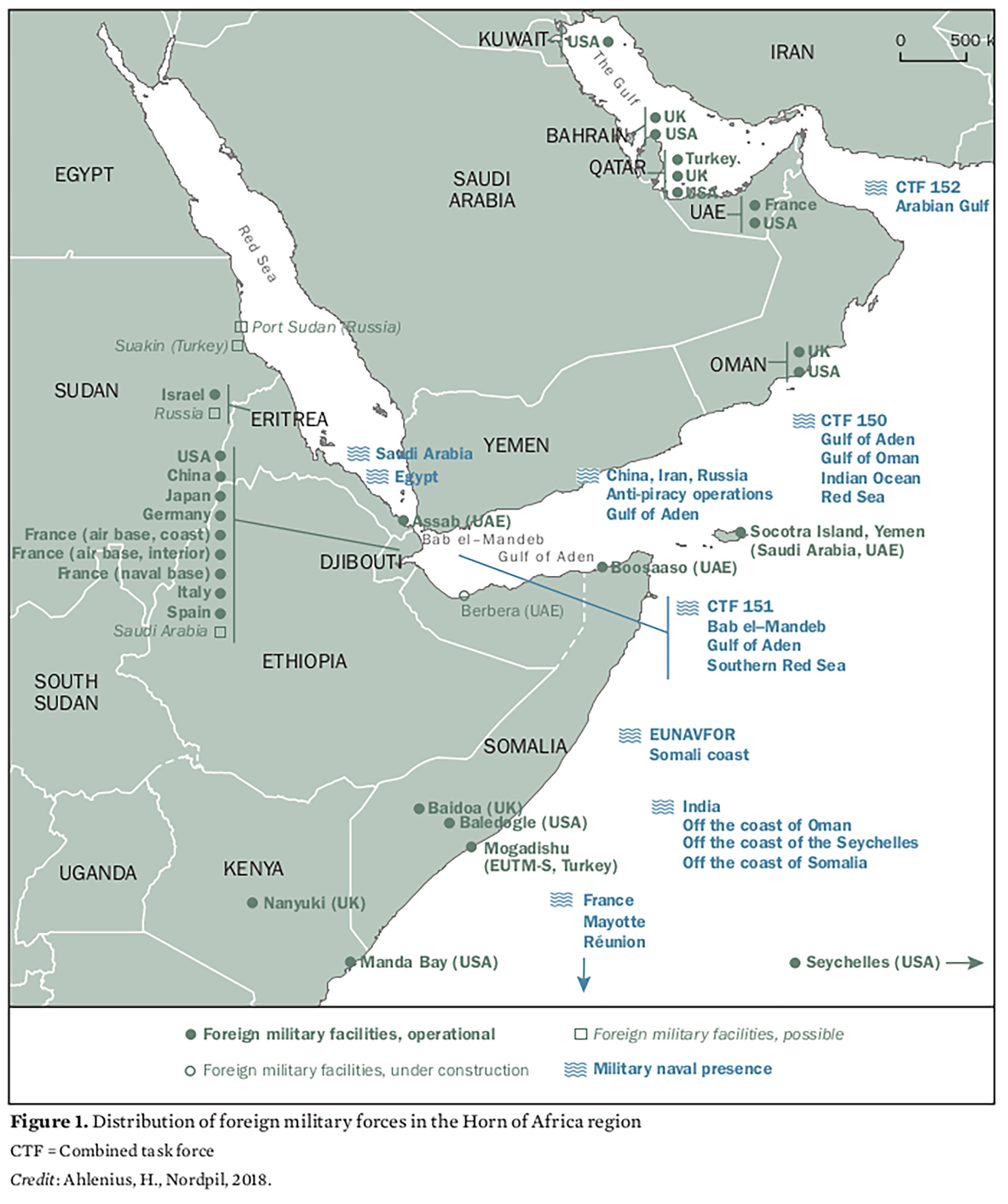

The Gulf of Aden is one of the world’s most frequented shipping lanes: 33,000 ships and seven percent of the global oil supply[1] pass through its waters each year. Not least because of its trade-crucial location, the Gulf has seen growing militarization. A regional and international scramble for influence contributes to this trend, resulting in the increasing construction of military facilities and accordingly to the deployment of naval forces (see Figure 1). While the international military presence has nearly halted the looting of ships by the infamous Somalian pirates, this has had no pacifying effect on the dire and intricate conflicts within Somalia and Yemen. The international military presence serves as an expression of tensions (see Box), rather than a basis for equitable regional peace. This is also apparent if one looks at arms transfers between the three states surrounding the Gulf: Djibouti, Somalia and Yemen. As will be analyzed below and provided they are willing, these transfers show the challenges to regional and international actors in curbing international weapons flows – be they licit, semi-legal or illicit.

Arms Transfers to Yemen

Even before the outbreak of the war, Yemen already had the second highest per capita possession of firearms globally.[2] The escalation of violence since 2015 has been accompanied by an influx of ever more weapons. The providers of these weapons to Yemeni actors can be divided mainly into two groups. On the one hand, forces supportive of the Yemeni government are primarily supplied with arms from so-called coalition[3] states. Arms transfers to these factions remain inadequately monitored, as there is no arms embargo imposed on these states (except for Sudan), nor on the Yemeni government. As a result, and tacitly accepted by the international community, the quantities and types of weapon systems provided by coalition states remain obscure.

Coalition forces assert that their actions are in line with UN Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 2216 demanding the restoration of the Yemeni government of Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi. However, the resolution remains highly disputed. The UN, as well as experts on international law,[4] have concluded that all major parties to the war in Yemen are in violation of international humanitarian law through such actions as “the indiscriminate bombing of civilian targets”[5] by coalition forces. The US, UK and France, however, remain the major arms-exporters to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Germany, too, has delivered vast amounts of weapons to coalition states.[6] This circumvents such international arms trade obligations as the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) and the EU Common Position on Arms Export Controls that “prohibit arms transfers from the moment there is a significant risk that they could be used to commit or facilitate grave breaches [of international law]”.[7] However, change seems possible as the new US President Joe Biden recently announced the halting of arms deliveries to Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

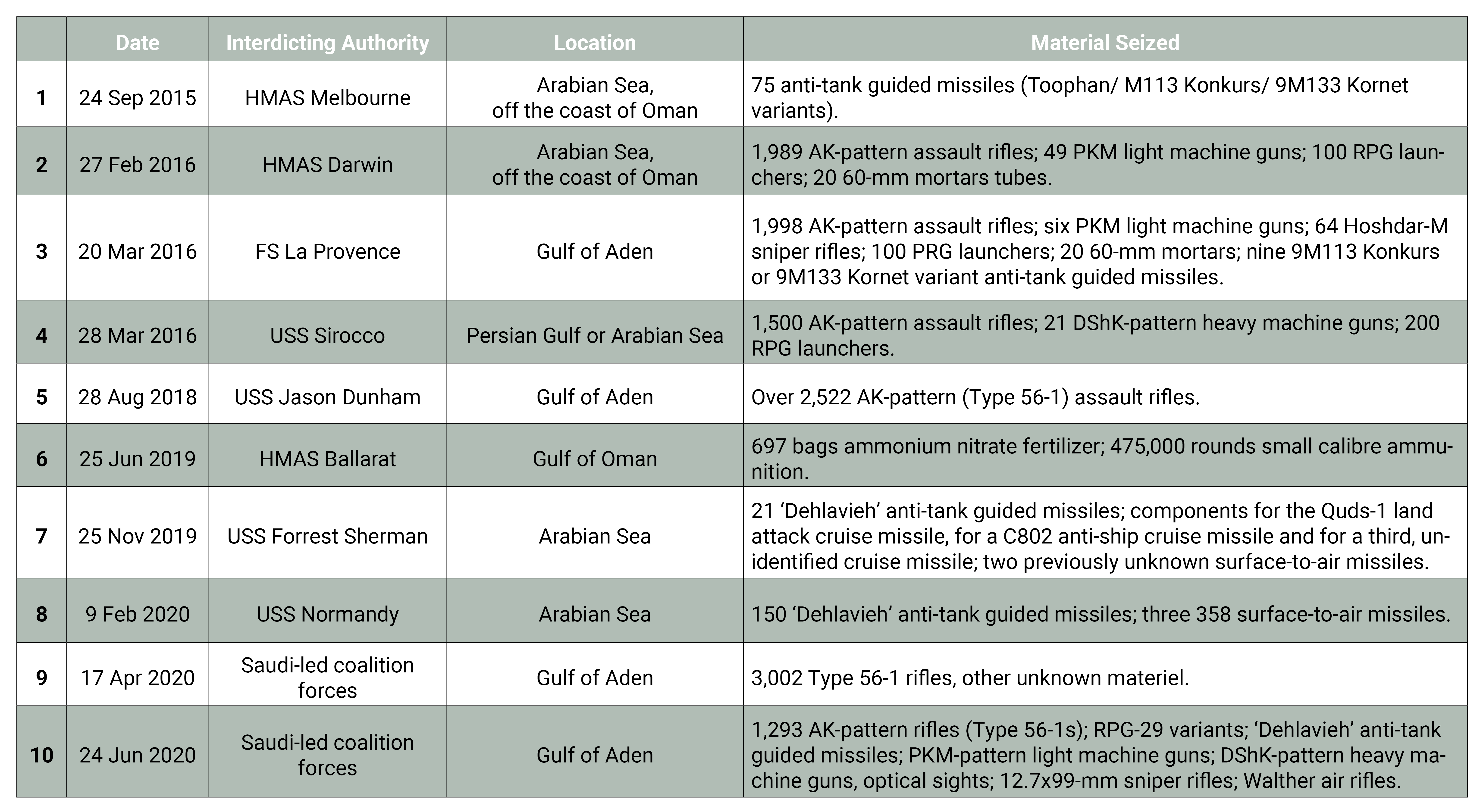

The opposing Houthi rebels, on the other hand, are subject to an UN imposed arms embargo, though official seizures by military vessels patrolling the Gulf of Aden prove they continue to receive sophisticated weapons that share “technical characteristics similar to arms manufactured in […] Iran.”[8] Furthermore, large quantities of Chinese manufactured rifles and ammunition – most probably also provided by Iran – have entered Yemen (for major official seizures see Table 1).

Arms transfers to Houthis are regularly carried out with medium scale private vessels (dhows). These transfers face interdiction by the coalition sea blockade that has fostered the severe humanitarian crisis in Yemen so present in international headlines. Arms transfers have reached Houthi rebels via an overland route, as well. Parts for armed drones and modern types of missiles are evidently reaching Yemen via Oman. It remains unclear whether the officially neutral Omani border patrols lack the capacity to curb the smuggling, or are bribed.[9] As will be elaborated below, ports in Djibouti and Somalia are used to ship weapons to Yemen, but flows in the opposite direction can also be observed.

The Construction of Military Facilities

Djibouti is a prime example for the militarization of the Gulf of Aden. The small state hosts military facilities of the US, China, Japan and several European countries, respectively underlining their influence aspirations. Likewise, regional powers are increasingly planning and constructing naval and cargo ports, as well as army bases, in the broader region. The United Arab Emirates (UAE), Turkey and Saudi Arabia, particularly, are upscaling their foothold (see Figure 1).

In addition to the Gulf monarchies’ longstanding lines of conflict with Israel as well as Iran, this trend mirrors the increasing rift between Qatar and Turkey on one side, and Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain on the other. Rents and infrastructural investments are used by these states to bind elites and to expand their political and strategic influence in the Horn of Africa. However, this strategy also encounters mistrust in, for example, Kenya and Ethiopia.

The Yemen-Somalia Connection

Weapons from Yemen, be they initially supplied to Houthis or forces supporting the Yemeni government, are increasingly finding their way to East Africa. This is particularly true for Somalia. The number of confiscated weapons transfers between the two countries’ coasts has grown in recent years, although it is not clear whether this is due to expanding trade or tighter controls.[10] Nevertheless, international naval forces intercept only a fraction of the illicitly traded arms.

Commercial and social ties between Somali and Yemeni nationals have a long history. Aside from the mostly legitimate trade, illegal cargo is commonly smuggled by private dealers between Yemen’s southern coast and the Bosaso district of Puntland (Somalia). Interviews conducted by the author with regional experts point out that expanding arms trafficking networks are partly connected with radical Islamist militias, showing overlap with former pirate groups. Moreover, the role of the Puntland authorities is ambivalent. While the state’s maritime police have seized weapons after receiving tips from international military forces, it is probably purchasing illegal arms from Yemeni dealers itself.[11] Arms traffickers move relatively freely in this area. As a result, an adjustment of the mandate of the anti-piracy mission of the EU Naval Force in Somalia (Operation Atalanta) aimed at the containment of such illicit maritime activities is currently being discussed.[12]

The Yemen to Somalia arms trade is particularly lucrative as rifles can be sold at three times the market price in the Horn of Africa state. The arms deliveries generally remain in Somalia, but seizures show that small amounts of these weapons also find their way to neighboring states.[13] However, a systematic trend is not (yet) observable.[14] Conversely, Puntland is likely used by Iran as a hub for arms deliveries to the Houthi rebels in Yemen.[15]

However substantial, iIllicitly transferred arms from Yemen are only a part of the weaponry utilized in Somalia. Many weapons in possession of domestic militias are older remnants, or have been captured or diverted from the Somalia National Army (SNA) and the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM). Although the SNA has denied the UN access to its stockpiles, the Somalian forces have licitly received vast numbers of weapons and ammunition[16] since the partial lifting of an existing arms embargo in 2013. Equipping the SNA should, therefore, be more critically assessed and monitored.

Djibouti, the New Trafficking Hub?

As in Somalia and Yemen, the Gulf of Aden state of Djibouti is significantly affected by regional arms flow dynamics – and by developments in its northern neighbor, Eritrea. Formerly, it was Eritrea that was often accused of being the focal point of regional weapons smuggling. For example, Iran used its Assab naval station in Eritrea to ship military equipment to Hezbollah, Hamas and the Houthis through the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea.

This trend has shifted in recent years. Following the 2018 peace agreement between Ethiopia and Eritrea, the latter is striving to shake off its negative international reputation. Iran’s influence in Eritrea has been replaced by the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Israel. Although denied by representatives of Djibouti, recent research shows that the small state is increasingly filling the gap left by Eritrea to become the regional hub for arms transfers.[17] For instance, reports indicate that Djibouti is now used as an intermediary for arms smuggled from Yemen to Somalia. According to eyewitness accounts, China uses its port in Doraleh (Djibouti) for illegal arms shipments to East Africa and Yemen.[18] In 2018, freights were detected consisting of multiple rocket launchers, anti-tank missiles, “and large quantities of Chinese […] ammunition.”[19] Although not inevitably provided by China, Chinese arms and ammunition are increasingly being found in East African conflict zones. Turkey and the UAE also illegally deliver weapons in the region through several entry points.[20] It has to be pointed out, however, that the majority of arms transfers to Africa continue to come from Western states and Russia.[21]

Allegations that the Djiboutian government accepts the illicit trade to balance its debt with China and to receive payments for personal gain are plausible. Nonetheless, international pressure on Djibouti remains low. The fact that major global powers – three of which have veto power in the UNSC – maintain military facilities in the small state (see Box) provides it with a strong negotiating position, and limits opportunities to curb the flow of arms.

Conclusion and Analysis

The Gulf of Aden is one of the most vibrant shipping routes in the world, though its largest surrounding states, Yemen and Somalia, benefit little from this trade and continue to host two of the globe’s direst and intricately violent conflicts. Legal and illegal arms transfers in the region fuel violence and mistrust at the expense of war-torn populations. In such an adverse environment, combined with local conflict particularities, attempts for a peaceful settlement of these conflicts are left with next to no chances to thrive.

At the UN level, arms embargoes have so far been the tool of choice to counter weapons circulation. They face several problems, however. Among them is the fact that arms embargoes in the region struggle against the low detection rate of arms deliveries. Countering the trade with the enforcement of naval controls, however, should be carried out by actors not directly involved in regional conflicts, and should be carefully tailored to local needs to prevent the destruction of legitimate livelihoods.

Although such technical solutions could possibly combat symptoms, the main problem lies at the political level. As long as embargo breaches remain chiefly without consequences, proliferation dynamics in the Gulf of Aden and elsewhere will not be curbed. To this end, European states should step out of their comfort zone to not only focus on what others do wrong, but on what they can do better themselves.

While assigning responsibility to international ‘bad boys’ is important, such a strategy does not do justice to more complex problems such as the regional interrelations of conflicts and arms diversions identified above. These could be more strategically addressed. For example, coalition forces continue to receive vast amounts of modern weapons systems from Western states while widely committing war crimes. In this context, European states regularly stretch legal interpretations of export authorizations to their fullest extent, and beyond. Governments that like to see themselves as spearheading multilateralism should set a good example by taking care to avoid the impression that international regulations can be observed in selective ways. The current halting of weapons deliveries by the USA and others states to Saudi Arabia and the UAE gives reason for hope.

The author is part of a cooperation program between the German Federal Foreign Office (GFFO) and PRIF. The views expressed in the text are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the position of the GFFO.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)

Matthias Schwarz

Latest posts by Matthias Schwarz (see all)

- Have the Tables Turned? What to Expect from Kenya’s New “Hustler” President William Ruto - 8. November 2022

- Arms Transfers in the Gulf of Aden. Shining the Spotlight on Regional Dynamics - 24. März 2021

- From Legal to Illegal Transfers: Regional Implications of Weapon Flows to Libya - 10. Dezember 2020