From Legal to Illegal Transfers: Regional Implications of Weapon Flows to Libya

The recent denial of access to a Turkish freighter for German soldiers of the European Union Naval Force Mediterranean Operation IRINI is the latest example of the difficulties arising from the UN-imposed arms embargo in Libya. Since 2011, countries such as Turkey, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Jordan, Egypt, Russia and France have continued to transfer large quantities of heavy military equipment to the North African State. But also Small Arms and Light Weapons (SALW) remain a major problem. Changes in the intensity of the Libyan conflict could lead to a growing spread of SALW in the whole region and further complicate the overall security situation at the expense of domestic populations.

Context

During the four decades of Muammar al-Gaddafi’s rule Libya became one of the most heavily armed states in Africa. After his overthrow in 2011, looting of weapons stockpiles led to a spread of arms within the country. Particularly Small Arms and Light Weapons (SALW) proliferated to West African conflict zones and terrorist groups. In addition to the weapons looted from Gaddafi’s stockpiles, further weapons deliveries entered Libya, equipping the two major factions of the ongoing conflict, the UN-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) and the Libyan National Army (LNA). The concurrent support of both – and several smaller and allied – factions mirrors the complicated and internationalized status quo of the conflict. In addition to these power competitions, some commentators have assessed that “Libya also became a kind of testing ground for foreign military equipment.” Although an arms embargo was imposed in 2011, which is meant to be enforced by the 2020 deployed naval mission EUNAVFOR MED operation IRINI (as successor of operation SOPHIA), weapons continue to flow into the North African State. While it is known that Unmanned Arial Vehicles (UAVs), Vehicles and other material have illegally entered Libya, the current status of SALW influxes remains more obscure.

Simultaneously, the security and social situation in the country has deteriorated since April 2019, a trend accompanied by the growing numbers of external fighters in Libya. The ones who suffer the most are the Libyan citizens, who have expressed their frustration and demands for political and socioeconomic change in increasing protest since the summer. After violent clashes intensified in the second quarter of 2020, a ceasefire agreement between GNA and LNA concluded in October has contributed to a fragile relief and offers a glimpse of hope. The resulting “Libyan Political Dialogue Forum” is intended to pave the way for elections on December 24, 2021. However, it is essential that in order to aid this process external forces actually leave the country as planned. So far, foreign fighters and mercenaries as well as GNA and LNA forces do not appear to be withdrawing. Against the background of these volatile dynamics, this text provides a snapshot of the dynamics of arms flows into, within and out of Libya.

The regional spread of SALW since 2011

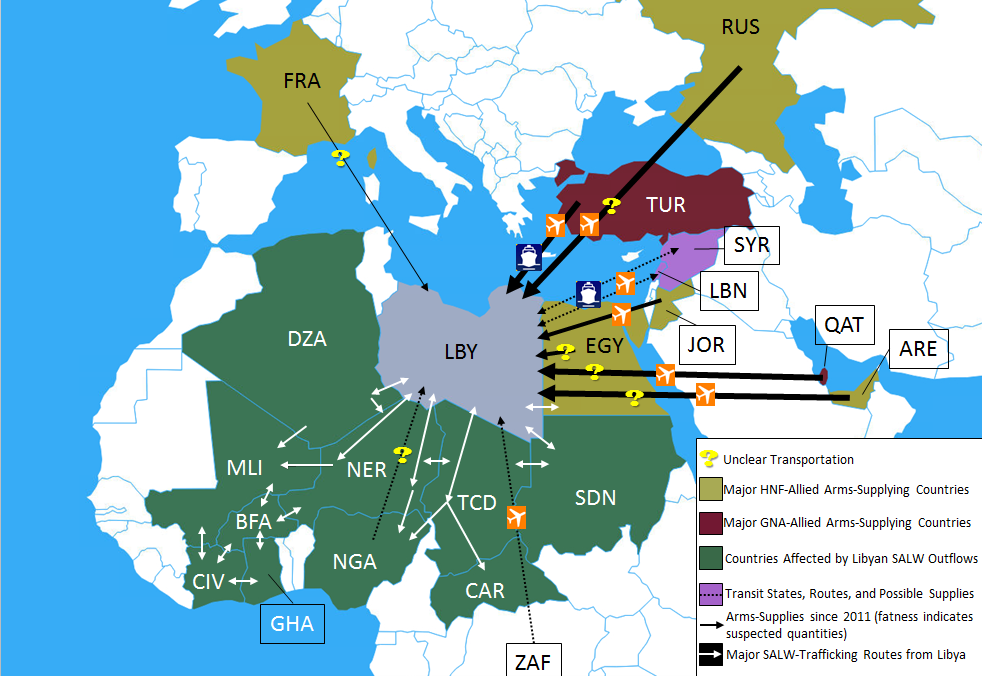

As indicated, the looting of stockpiles during and after the overthrow of Gaddafi led to a growing regional availability of SALW and munitions. It is estimated that these stockpiles contained 250.000-700.000 firearms. This reinforced the already existing dynamics of violence not only in Libya but the whole region. Particularly between 2011 and 2014, transiting through Niger, Chad and to a lesser degree Algeria, weapons of the Gaddafi-era found their way to insurgents and terrorist groups inter alia in Mali, Central African Republic (CAR) and northern Nigeria but also in Darfur, Syria and Lebanon. Even though a previous arms embargo had already been put in place from 1992 to 2003, SALW manufactured in Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, China, France, Germany, Italy, the Russian Federation, Serbia, South Africa, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and others, which potentially entered Libya during that time, have been identified circulating in the North African state. Most of these weapons are self-loading rifles and handguns. However, also mortars, rocket launchers and the like are spreading since 2011. In addition, French, German, Qatari and UAE marked rifles and anti-tank guided weapons and missiles entered Libya between 2011 and 2014. Furthermore, stolen Austrian Glock handguns intended for the European Border Assistance and others used by US forces in Libya have been identified on-site.

However, the regional spread of SALW and munitions originating from Libyan stockpiles has decreased since 2014. This has mainly been attributed to two factors: (1) The number of available weapons in Libya is declining since the local demand for weapons within Libya has increased; (2) The cross-border mission Operation Barkhane of Mali, Niger, Chad, Mauretania, Burkina Faso and France has impaired the major smuggling routes. Nevertheless, military operations have at best been able to combat symptoms and not the underlying conflict structures. Reportedly, many illegally transferred arms are currently finding their way back to Libya. However, this does not mean that the respective dynamics cannot be reversed. For example, a report of the Small Arms Survey indicates that due to a regional – currently lessening – gold rush in the “Chad-Sudan-Libya Triangle” the demand for weapons in northern Chad “remains relatively high”.

Growing demand and markets within Libya

The SALW-flow dynamics reversed to Libya when forces of the UN-recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) started an extensive military offensive against Islamist groups in May 2014. This marked the starting point of the co-called Second Libyan Civil War. Although the conflict is characterized by a multitude of fighting factions, it is generally split along two major blocs, the GNA and the Libyan National Army (LNA) under the lead of General Chalifa Haftar. The war has induced the growing demand for SALW primarily for two reasons: First, the increasing intensity of fighting boosted the request for weapons for all factions involved in the conflict. Second, the overthrow of Gaddafi has led to a growing number of firearms in civilian possession. Hence, the autocratic enforcement of internal stability and the monopoly on the use of force has been replaced by an opaque and fragile security environment. This has led to an evolving “gun culture” also within unaffiliated civilian domains. Libyans increasingly acquire weapons “to defend their homes and businesses, and for personal protection outside the home” but also for reasons of prestige.

The market for these SALW and munitions is mainly centered in bigger cities and readily accessible social media groups (mainly Facebook). In the latter case, firearms are offered quite openly. Dealers seem to be private persons and non-state armed groups alike that replenish their budget. Apart from the primarily offered self-loading rifles and handguns, heavier weapons, military equipment and munitions are also available. Likewise, due to their cheapness and their easy convertibility to lethal weapons, there is evidence of a considerable demand for Turkish fabricated blank-firing weapons.

Influx of new weapons

Recently, the cases of heavy weapons entering Libya became particularly prominent. While the GNA is chiefly support by Turkey and Qatar, the LNA enjoys support from UAE, Jordan, Egypt, Russia and France. This support is underscored by militaries and paramilitaries fighting on both sides. For example, Turkey has sent approximately 2.000 fighters from Syria to the North African state. Also, the Russian paramilitary Wagner Group is operating in Libya, and has been accused of laying landmines and improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in populated areas. Additionally, Chadian and Sudanese armed groups have been fighting for various factions as intermediaries or local allies. These factions could at some point return and intensify conflicts in Darfur and Northern Chad.

Besides the (para-)military involvement on the ground, supporting parties continue to bypass the persistent arms embargo by smuggling weapon systems to Libya. The recent refusal of a Turkish freighter to be intercepted by a German frigate (accompanied by subsequent protest by the Turkish defense Ministry) underlines this. The major share of weapons provided to the GNA are said to come from Turkey and Qatar while the LNA mainly obtains new arms from the UAE, Jordan, Egypt and Russia. Neither Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj (GNA) nor General Haftar (LNA) conceal this illegal support. The majority of known weapon deliveries to Libya since 2019 are military vehicles, UAVs, offshore patrol vessels and other ships, surveillance and jamming systems and supplementary material. Libya is therefore seen by some commentators as a “testing ground” for novel military equipment.

This becomes particularly apparent with regard to armed drones. While the GNA has been supplied with Turkish Bayraktar TB2 combat drones, Haftar’s forces are known to possess Chinese Wing Loong II UAVs which were most-probably provided by the United Arab Emirates. The “capabilities of each UCAV [unmanned combat aerial vehicle] system shows that LNA currently has a significant tactical advantage”. To fight the drones, Russian-built high-altitude air defense systems – potentially provided by Egypt – have currently been located in eastern Libya.

Being difficult to detect via satellite and drone imagery, the current influx of SALW to Libya is even easier to conceal. In December 2018, two inspections uncovered the intended delivery of 23.000 blank firing pistols of Turkish production. Between January and March 2020 at least four ships carrying military equipment from Turkey entered the ports of Tripoli and Misrata. Furthermore, shoulder-launched anti-tank rocket systems, which are solely produced by Jordan since 2013 and French anti-tank guided missiles systems have been used by the LNA. In addition, considerable numbers of Belgian rifles “are believed to have entered Libya in recent years” which were originally provided to Qatar and the UAE. Moreover, novel Sudanese, Russian and Chinese ammunition as well as ammunition from the German Rheinmetall branch Denel in South Africa have been detected in Libya. Furthermore, the United States alleges that Russia – besides providing MiG jet fighter aircrafts – has been flying Wagner fighters and military equipment to Libya.

Outlook

After 2011 Libya has not only lapsed into war but has also become a site of regional power competition. In addition to the already circulating weapons looted from national stockpiles, the major fighting factions persistently and illegally receive military equipment from external powers. Meanwhile the course of the conflict remains tense. The humanitarian situation is dramatic and the number of victims and displaced persons is high. The recently concluded ceasefire is a first step in the right direction. However, a de novo escalation cannot be ruled out.

The events in Libya bear the potential of destabilizing the entire region. Although desirable, a decline in the intensity of the war in Libya might reverse arms flows (particularly SALW) into nearby states. Existing smuggling routes via Niger and Chad to West Africa could regain significance. But also states like the CAR are endangered by a growing influx of weapons. This holds similarly true for Sudan and Chad which face the additional risk that returning combatants from Libya will reinforce the already existing volatility back home. Furthermore, the war in Libya has – besides other reasons – led to an advanced military buildup of its neighboring states Algeria and Egypt. To enclose regional conflict dimensions, the understanding the involvement of Libya’s neighbors is paramount. However, support has to be assessed very carefully since blind or misdirected action can evidently exacerbate problems. Hence, holistic and long-term approaches that are reconciled with other political and policy domains besides the economic inclusion of civilians should be pursued.

Equally important is that identified embargo-violators should – as is currently the case – not be provided with European weapon systems. The diversion of arms is a well-known problem. In this context, international obligations like the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) and the EU Common position on Arms Export controls should be strictly observed. For example, ATT Article 6 (1) states that “if the transfer would violate its obligations under measures adopted by the United Nations Security Council”, no export authorization shall be granted. 10 percent of the weapons offered on Libyan online markets still originate from the North African campaign of World War II. The longevity of SALW, which can only sparsely be compensated by weapons destruction, should always be considered when exporting arms.

The author is part of a cooperation program between the German Federal Foreign Office (GFFO) and PRIF. The views expressed in the text are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the position of the GFFO.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)

Matthias Schwarz

Latest posts by Matthias Schwarz (see all)

- Have the Tables Turned? What to Expect from Kenya’s New “Hustler” President William Ruto - 8. November 2022

- Arms Transfers in the Gulf of Aden. Shining the Spotlight on Regional Dynamics - 24. März 2021

- From Legal to Illegal Transfers: Regional Implications of Weapon Flows to Libya - 10. Dezember 2020