Populism, executive assertiveness and popular support for strongman-democracy in the Philippines

Populists are supposed to thrive on their ability to mirror, condense and radicalize popular demands ignored by establishment politicians. This sketch on the election-promises and later policies of Philippine strongman Rodrigo Duterte suggests that their success is less dependent on any pre-existing radical popular demands, but on their authenticity as leaders who get things done and realize a government that is perceived to work for the people. The “success” of and widespread approval for Duterte’s deadly anti-crime campaign suggests that Philippine democracy is at a crossroad.

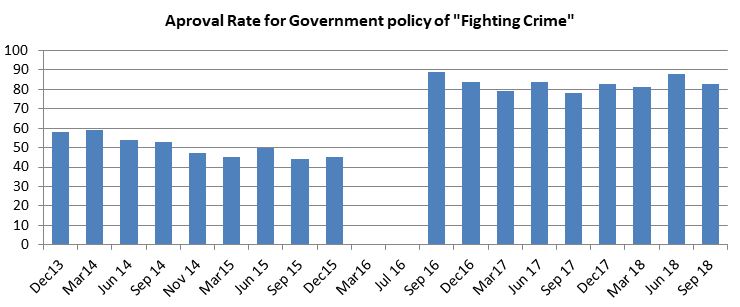

On May 10, 2016, Rodrigo Duterte gained a resounding victory in the elections for the next President of the Philippines. This was generally attributed to his populist appeal, his contrasting himself as a representative of the people against a dominant elite that held Philippine democracy hostage to its political and economic interests. Of equal importance was his image of a politician, who was willing and able to implement his promises against resistance if necessary, a politician that would not succumb to the eternal woes of Philippine democracy: corruption and clientelistic exchange of favors amongst the dominant families. The largest attention, however, caught his repeated promises to eradicate drugs and drug crime from the Philippines within three to six months, if necessary by killing criminals and druglords. After his election, he acted on his promises by instigating an anti-drug campaign in which several thousand suspects were “neutralized” by the police in so-called armed encounters. Even though Duterte was elected by only 39 percent of votes, public support for his campaign has been overwhelming at around 80 percent and more.

Was Duterte elected for President, because he successfully “politicized latent anxieties about crime and social disorder […] to argue […] that progress would have to come at the price of liberal rights?” I argue that this understanding takes for granted what actually needs closer inspection: the temporal order of a pre-existing popular demand for a tough anti-crime policy that is ignored by the establishment-elite and only taken up by a revisionist leader.

First, one should remember that Duterte was elected on an eclectic policy platform that was much broader than the single issue of a deadly war on drugs. Duterte united a host of seemingly rather incompatible political positions, as self-proclaimed Socialist with good contacts to both the Muslim and the Communist rebels, as a critic of the Catholic Church and champion of LGBT rights, and a supporter of federalism with his image of a no-nonsense politician devoted to eradicate crime. This made it possible vote for him “because he is the most progressive presidential candidate that this country has ever had.” His swearing, blaspheme, public threats and vulgar demeanor could be reinterpreted as going against the exclusionary cultural practice of domination through social habits and education. This made it possible to imagine Duterte as an organic intellectual who “aims to win consent to counter-hegemonic ideas and ambitions.” He also promised a policy that shifted from a consumption driven economy to one based on production, with a strong focus on infrastructure aimed at a pro-poor policy and the non-metropolitan regions bringing him the support of prominent development economists as Ernesto Pernia, who became Duterte’s leading crafter of economic policies. Clearly to Filipinos, Duterte was much more than “The Punisher” or “Dirty Harry” from the Philippine South.

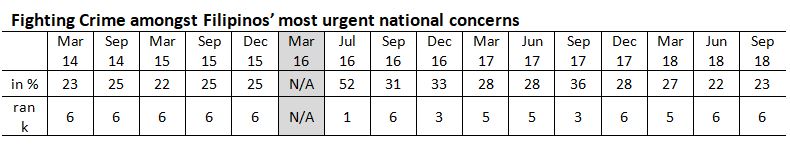

Second, there is hardly any evidence that Duterte’s plea for solving the crime problem by killing criminals mirrored, condense and radicalized pre-existing popular demands. Surveys on public anxieties, on perceptions of and experiences with crime do not validate the assumption of a prior public shift towards punitiveness. The quarterly Pulse Asia surveys on the people’s most urgent national concerns had “fighting criminality” persistently ranked sixth only for the past years up to the presidential campaign, lagging far behind much more pressing concerns like controlling inflation, improving workers’ pay, fighting corruption, reducing poverty and creating jobs.

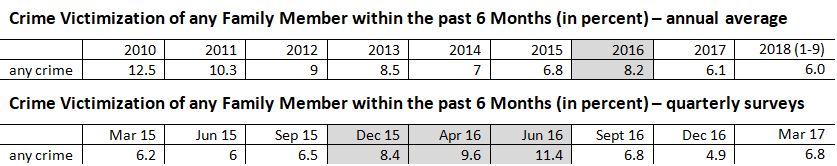

An analysis of Filipinos’ experience with crime victimization brings similar results. Reported crime victimization of family members declined from 2010 to 2015. Reported crime victimizations rates only rose during the months of the Duterte campaign, when the topic was hot on account of Duterte’s elevation of drug crime to a national security problem and his promise to solve it within six months.

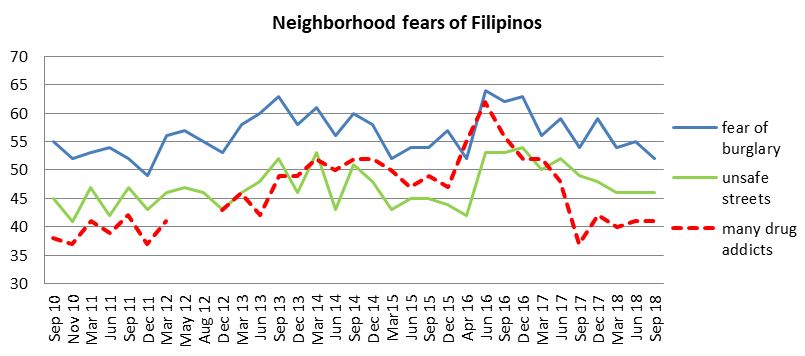

The analysis of neighborhood fears should signal most strongly any shifts in popular demands for a harsher strategy of crime-control. Evidence is mixed, with fear of burglary and fear of unsafe streets being rather stable over the past five years, whereas fear of “many drug addicts” clearly rising. However, this trend seemed to have been broken in 2015, when all three types of neighborhood fears receded. As with the other neighborhood fears, fear of drug addicts escalated dramatically only during the election campaign and not before.

In total, this suggests that the punitive shift of the Philippine public is largely a short-term product of a campaign and vast media coverage of the Duterte’s tough talk on crime as a national security threat. Following elections, crime as a national concern, crime victimization and fears receded to pre-election levels with the single exception of fear of drug addicts that dropped to its lowest level since 2012. Taken together with the high approval rates for Duterte’s anti-crime campaign this signals that in the public eye Duterte’s campaing was generally perceived as achieving its aim.

Even though available data suggests that the public shift towards punitiveness may be a product of the Duterte campaign, this shift has enduring consequences. The enduring and broad support for Duterte’s ‘shoot first, ask questions later’ policy of crime control signals that he has successfully established a new paradigm of crime fighting that focuses on tough crime control at the expense of due process orientation.

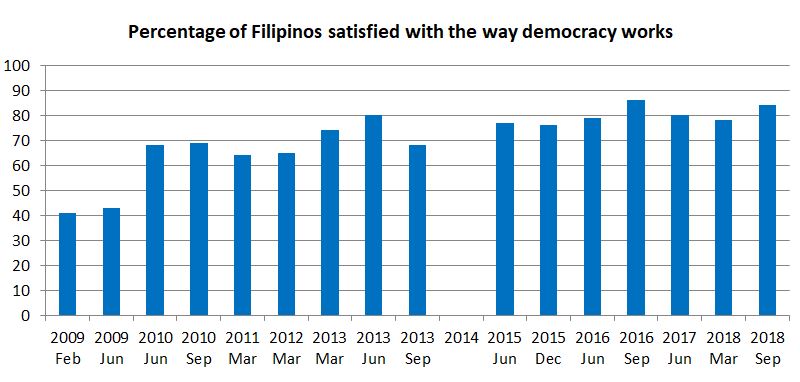

Clearly, to Filipinos their current government is doing a good job in fighting drug-crime. Further, despite the current administration’s illiberal policies the percentage of Filipinos satisfied with the way democracy works in the Philippines is at a similar or higher level than during the current President’s predecessor’s term.

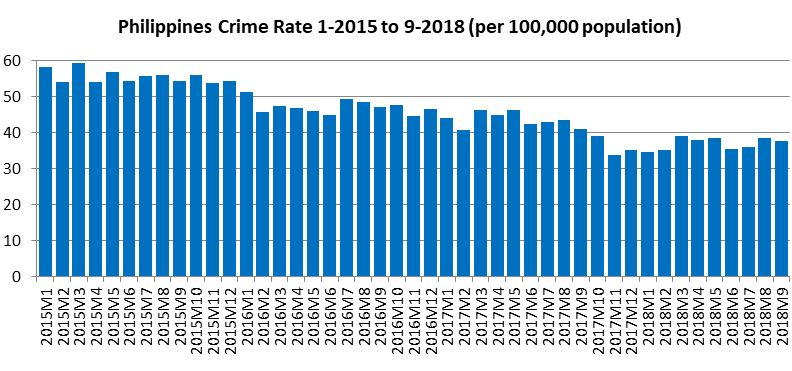

The extraordinarily high approval rates as well as the almost complete lack of concern about the illiberal turn of Philippine democracy signal that the current administration succeeded in convincing a large percentage of those Filipinos who did not vote for Duterte that his way of doing politics is in the Filipinos’ best interest. This perception of a successful anti-crime strategy is underscored by a continuous drop in crime.

Even critical media report that all types of crime dropped significantly in 2017 and then again in 2018 with local police in all regions regularly reporting significant reductions be it in provincial capitals like Bacolod, in self-governing cities like Davao, in provinces like Bohol, or in the National Capital Region. As the downward trend of crime clearly preceded the Duterte presidency, the attribution to the deadly campaign of the Duterte administration is clearly premature. This, however, is completely neglected in the multitude of success messages that are regularly reported in the Philippine press.

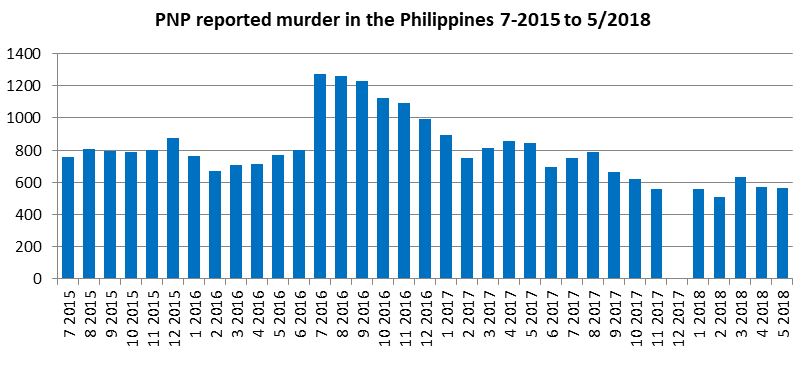

Compared to the perceived “success” the costs – a murder rate that rose dramatically during Duterte’s first year in office – easily pales when viewed from the perspective of the ordinary citizen who has much more to grapple with physical injury, theft and robbery than with the comparatively rare cases of murder and might therefore be willing to pay the price. Duterte’s strategy seems even more convincing as in the meantime the murder rate has dropped to a low not seen during the past years.

The above analysis showed that a punitive popular demand can be created by radical populists, who know the ropes of the modern media democracy. During the past years in office the Duterte administration managed to present its strategy of repressive crime control as successful. It convinced the majority of those who did not vote for Duterte that killing criminals is indeed a viable option for enhancing public security, despite the costs that have to a large extent to be borne by members of marginal communities.

This is clearly bad news for Philippine democracy and beyond, as Duterte’s perceived “success” in repressing crime provides one important pillar of domestic legitimacy for a regime that scraps much of the essentials of democratic governance. Given the overwhelming turncoatism of the Philippine political elite chances for a convincing alternative to Duterte’s “democratic” strongman-rule are dim.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)