Duterte’s war against drugs in the Philippines: Continuity and change

Since the election of Rodrigo Duterte to President of the Philippines, the Philippine National Police has waged an unrelenting war against drug crime that cost the lives of thousands of suspects. A spatial and temporal analysis of the past 30 months suggests that violence is slowly receding. While the situation is still highly problematic, a number of positive developments suggest that in an increasing number of provinces police violence is slowly returning to its pre-Duterte levels. While the master-key for ending the killings lies with the central government, provincial governments can do their share to mitigate the deadly repercussions of the Duterte government’s drug war.

On July 1, 2016 Duterte was inaugurated as President of the Philippines. At the very same day he set in motion a campaign against drug crime that resulted in the killing of several thousand suspects by the police in so-called legitimate encounters. Here I want to take a closer look at the development of fatal police violence after two and a half years. I argue that the police killings of suspects came in three distinct waves, that each of these was at a lower level than the preceding one and that this violence has been concentrated in a small number of regions and sub-regional units (provinces and cities). A comparison with pre-Duterte data on police use of deadly force shows that this violence is highly path-dependent. It also becomes visible that in the course of the campaign a shift occurred away from the National Capital Region (NCR) towards directly adjacent regions of the NCR and to a lesser extent to the Visayas in the middle and Mindanao in the South of the Philippines. Finally, I argue that macro trends tend to obscure huge temporal and spatial variation at the provincial level, which suggests that provincial governors can exert significant influence on police behavior and killing-ratios either to the better or the worse.

Three waves of police violence under Duterte

In the news the killing of suspects during the past years of the Duterte presidency is generally viewed in a holistic fashion. Yet, it came in three distinct waves, with the first from July 2016 to January 2017 being the by far most severe with a killing rate of approx. 200 suspects per month, whereas the following waves had a monthly “kill-rate” of approximately 80 (based on data provided by ABS-CBN, which compared to incoherent “official” data by the Philippine National Police (PNP) should underreport actual rates by approx. 30-40 percent). Even though then, the ABS-CBN dataset is incomplete, this only partly impinges on the violence trends over time. Both the ABS-CBN- and the PNP-data show that significantly more suspects were killed by the PNP in the last six months of 2016 than in any of the following years.

In the second half of 2016 ABS-CBN documents 1,452 deaths resulting from police encounters. For 2017 it documents 894 and for 2018 1,051 deaths. Roughly corresponding data from the Philippine National Police suggest 2169 police killings in the second half of 2016, approx. 1800 in 2018 and 1150 in 2018. Whereas in the initial phase to January 2017 the death toll approximated 20 times the number that could be documented by the author for the five years preceding the Duterte presidency (225 killed per year on average), this dropped to 8 times in 2017 and five times compared to the pre-Duterte level in 2018 (based on PNP data).

Spatial variation and path-dependency

Two outstanding features of pre-Duterte and Duterte-period police violence are the huge amount of spatial variation and path-dependency. Of the 98 subnational units (provinces and component parts of the NCR) 36 did not even have one documented case of a police use of deadly force for the decade of 2006 to 2015. 18 of these seem to have continued with this clean slate during the first 30 months of the Duterte anti-crime campaign. On the other hand ABS-CBN documents 14 subnational units with more than 50 killings from July 2016 to December 2018. For the top-scorer, the province of Bulacan (3.3 mill inhabitants), 676 police-killings were recorded, followed by 373 for Manila City (1.8 mill inhabitants) and 303 killings in Quezon City (2.9 mill inhabitants). While the overall magnitude of police violence rose dramatically during the Duterte campaign, the patterns of regional variation were rather similar to pre-Duterte police violence. Those that scored high before Duterte constituted the top-scorers under Duterte, whereas low-violence units reacted only hesitantly to the new course.

The shift away from the National Capital Region

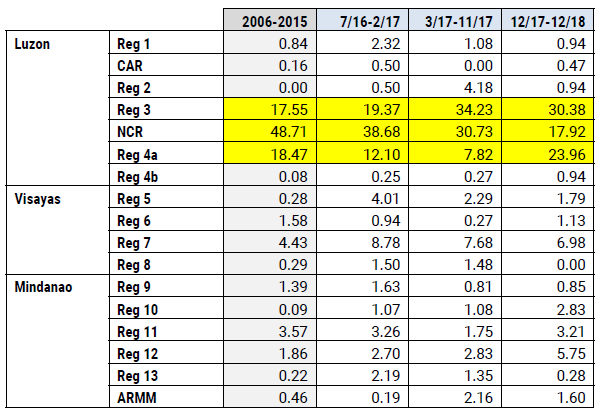

One of the most stunning effects of the national campaign against drugs is a decisive shift of police violence away from the NCR into those regions directly adjacent and, to a lesser degree, a shift from Luzon to the Visayas and Mindanao. Whereas for the decade before Duterte police killing of suspects in the NCR accounted for 49 percent of the total, this already fell to 39 percent during the first wave of killings (7/2016-2/2017), only to fall further to 31 and 18 percent during the following waves up to December 2018. In contrast the share of Region 3 directly adjacent to the north of the NCR doubled from 17 percent of all killings before Duterte to more than 30 percent in the 2017 and 2018 waves of police violence. While most of the violence still happens in Luzon, its share has been reduced by approximately 10 percent during the Duterte campaign.

Suspects killed by the PNP in the various regions in percent of total suspects killed in the Philippines

Variation in the severity of the problem of police killing of suspects becomes visible if one relates the numbers of suspects killed to the regional population. The figure below that compares pre-Duterte and Duterte patterns illustrates the concentration of pre-Duterte deadly police violence in the NCR and to a lesser extent in adjacent Region 3 as well as the shift from the NCR to Region 3 during the 30 months from July 2016 to December 2018. Before Duterte none of the other regions had a share in police-killings that approximated or exceeded its share in national population. While this still holds true for all but one (Region 7) of the regions, the Duterte campaign brought about an overall rise in the vast majority of regions traditionally characterized by rather low shares of police-violence throughout the Philippines.

The provincial level

As before also under Duterte, it is the provincial level that provides the clearest picture of police use of deadly force. In almost all regions with higher levels of deadly police violence, this can be attributed to one or two provinces (or component cities in the NCR) only. For example, of the overall total of 885 killings reported by ABS-CBN in Region 3 for July 2016 to December 2018 a full 676 happened in the province of Bulacan, followed by 87, 57 and 29 in the next three provinces. In the NCR more than two thirds of the police violence occurs in Manila and Quezon City, even though those two only comprise approx. 36 percent of the population. Provincial level analysis also allows to show that in a number of local government units current levels of police violence have already been reduced to pre-Duterte or even lower levels during the last phase of the anti-drug campaign. This has been the case in Las Pinas, Malabon, Mandaluyong, Marikina, Muntinlupa, Navotas, San Juan, all in the NCR, as well as in the provinces of Aurora, Masbate,Aklan, Capiz, Southern Leyte, Leyte, Northern Samar, Samar, Compostela Valley, Davao Oriental, Agusan del Sur, Surigao del Norte, Sulu and Tawi-Tawi. In the NCR’s city of Manila, the ratio of suspects killed per million inhabitants has been reduced from 13 times to 2 times, in Caloocan it dropped from 25 times to 2.4 times the average of the pre-Duterte decade.

Cautious optimism for the future?

This short sketch of temporal and spatial patterns of fatal police violence establishes an ambivalent picture. On the positive side, deadly police violence is clearly receding. However, the last wave still is at a level far higher than police deadly use of force during the decade preceding the Duterte presidency. The most positive result is that despite overall high levels, police violence in the National Capital region is declining at a faster pace than in the rest of the country.

While the police as a hierarchical multi-level institution functions as a transmission belt for central stimuli, the huge amount of variation on the provincial level signals that police use of deadly force can be influenced by other political actors at the subnational level. Central directives and variation in local levels of drug crime provide only a partial explanation for temporal and spatial variation. Equally important are local chief executives’ attitudes on local crime and its control as well as the incentives for or against violence emanating provided by them. In the coming months and years theirs will be a crucial role for countering the dynamics for more police use of deadly force activated by the Duterte campaign against drugs that has just been given a new boost by the President vowing “I still have three years. […] I will really finish the war against drugs in three years’ time.”

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)