Democracy on the Razor’s Edge: The 2022 Presidential Elections in Brazil

Brazil’s presidential elections are scheduled to take place on October 2, 2022. The confrontation between the extreme-right incumbent president Bolsonaro and the center-left former president Lula Da Silva provides a rare setting. The election places Brazil at a crossroads and will set the stage for either a comprehensive commitment to democracy under Lula or a continuation along the path to authoritarianism under Bolsonaro. Recent polls suggest that the most likely scenario is a win for Lula. Nevertheless, Brazil’s democratic institutions are continuously under attack. Currently, the possibility of the elections being preemptively cancelled or the final results being contested cannot be fully dismissed.

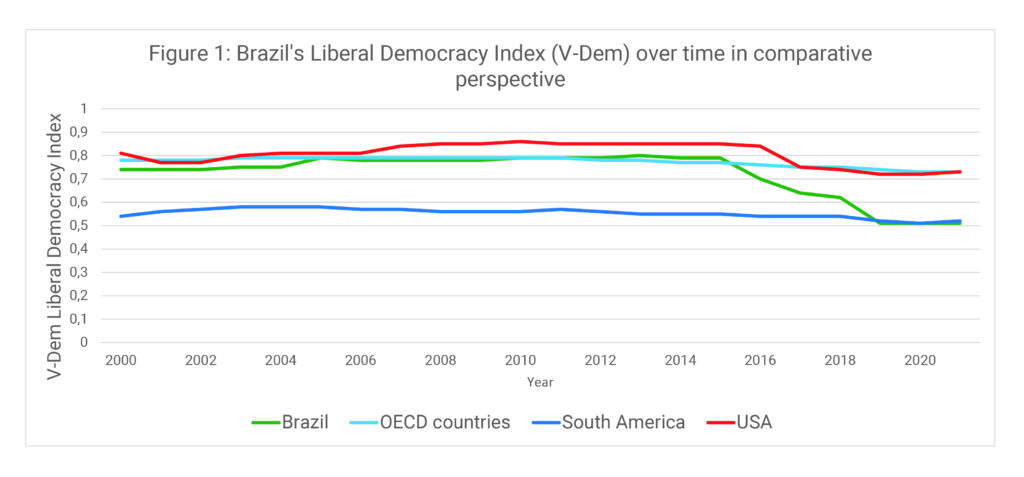

October 2, 2022 will see the first of two rounds of presidential elections take place in Brazil. Over the past few months, the incumbent extreme-right populist Jair Bolsonaro and the center-left Luis Inácio Lula Da Silva (president from 2003–2010) have emerged as the two candidates who will go head to head in the election run-off. Other candidates, such as Ciro Gomes and Simone Tebet, presented themselves as an alternative or “third way”1 to Bolsonaro and Lula, but they are unlikely to wield very much clout in the elections. The polarized election race dramatically illustrates the razor’s edge on which Brazilian democracy is currently standing: In recent years, the country’s rank in the Liberal Democracy Index2 has significantly declined (see Figure 1). Given that a Lula presidency would entail a more reformist and socially oriented government, whereas a second term for Bolsonaro would see Brazil further shift into authoritarian waters, an assessment of the upcoming elections is of crucial importance.

Figure 1: The Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Liberal Democracy Index ranges from low to high (0-1) and captures the level of free and fair elections, freedom of association and expression, the protection of civil liberties and inter-institutional checks and balances. Source: https://www.v-dem.net/data_analysis/CountryGraph/

The Weakening of Democratic Institutions under Bolsonaro

The incumbent in the race is Jair Bolosonaro, a former army captain with seven consecutive terms as a federal deputy. For years, Bolsonaro was seen as a figure of ridicule who regularly appeared in tabloid TV shows because of his antidemocratic and conservative positions and was known for his controversial sexist, misogynist, racist, and homophobic statements. In 2018, he emerged as an underdog in the presidential race, running for a small party without the endorsement of traditional politicians or sound financial backing. In absence of a solid party background, Bolsonaro built up and maintained power through personal ties and networks, not only with nationally and internationally known allies but also via direct interactions with his supporters. Through an extraordinary campaign strategy based heavily on social media networks, he successfully channeled the Brazilian people’s frustration and disillusionment with politics through an antiestablishment, anticorruption, conservative, and polarizing discourse, garnished with the issuance of fake news.3 In 2018, he was elected president with 55 percent of the vote in the second round.

Bolsonaro’s presidential term was marked by international isolation, deforestation in Amazonia, poor economic growth, and increased food insecurity. His disastrous handling of the COVID-19 crisis has been characterized by trivialization, scapegoating, and misinformation and has cost more than 680,000 lives.4 Although his government gradually lost support,5 Bolsonaro still maintains a core of vocal, active, and loyal supporters comprising around 15 percent6 of the population. Bolsonaro has kept these supporters on board by creating an atmosphere of constant confrontation and chaos, while arguing that he requires support to counter his obstructive opponents.

Although Bolsonaro’s power is limited by the Constitution, he knows how to increase it de facto. Corruption scandals have also emerged in his government, and he has acted to weaken and co-opt the institutions of accountability and control. In his relationship with the other branches of government, Bolsonaro has constantly sought to destabilize the system of checks and balances. With regard to the Congress, he established a cronyistic alliance with the old politics he had sworn to fight. This quid pro quo relationship7 involves offering significant control over the federal budget to selected members of Congress in exchange for turning a blind eye to the president’s outbursts. Currently, more than 145 different impeachment petitions8 against Bolsonaro are stalled in Congress. He has engaged in heated disputes with state governors9 and established a hostile and dysfunctional climate around topics such as pandemic management and fuel prices, imposing his will and seeking to establish a top-down relationship aimed at concentrating power in the federal executive. The most confrontational relationship, however, is with the Supreme Court; Bolsonaro wages constant attacks against any judges signaling a desire to control his persistent antidemocratic tendencies. At the same time, Bolsonaro has also been questioning the Brazilian electoral system10 and bespeaking its susceptibility to fraud. Such claims are used to incite loyal supporters against institutions and authorities and to maintain a climate of tension and distrust that contaminates the elections.

Another hallmark of Bolsonaro’s presidency is his proximity to the armed forces: Military personnel hold positions in several areas of the executive, some schools have been militarized, and the armed forces seek to increase their influence in the electoral process. At one point 36 percent of Bolsonaro’s ministerial cabinet11 were military personnel. Overall, more military personnel are part of Bolsonaro’s government than under the military regime (1964–1985).12 The number of military personnel in civilian positions in the federal government exceeds 6,000,13 an increase of more than 500 percent compared to the first Lula administration. This militarization is alarming given that the involvement of military personnel in politics constitutes a substantial element of autocratic regimes,14 thus hinting at the path Brazil may embark on under Bolsonaro’s second government.

Lula and the Promise of the Past

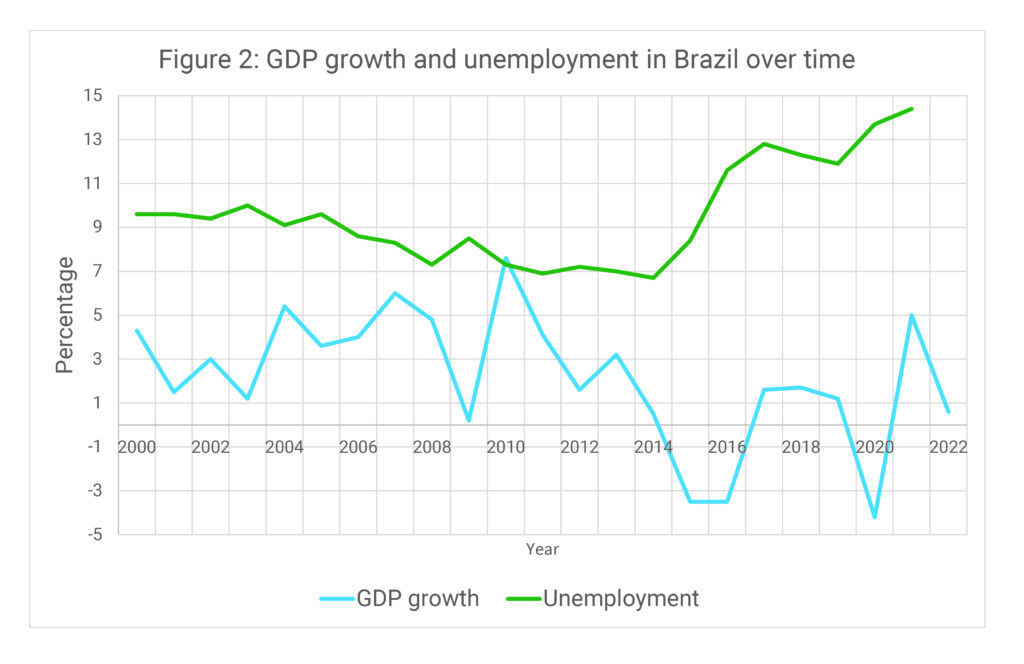

Lula, front-runner and founder of the Workers‘ Party (PT), represents an iconic figure of the Latin American left. Characteristic of Lula’s first two presidential terms were progressive reforms such as Fome Zero and Bolsa Familia, which helped lift millions of people out of poverty. Over the course of his time in office, Lula managed, inter alia, to considerably reduce unemployment and precarious employment (see Figure 2).15 Besides these achievements, he also engaged in a foreign policy promoting Brazil’s global influence and institutional embedding in the region. Lula ended his era with an approval rating of more than 80 percent making him Brazil’s most popular president. However, members of his government also faced corruption charges, which involved overbilling and payments to secure favorable votes in Congress. Subsequently, the impeachment of his successor Dilma Rousseff in 2016 precipitated a crisis for the PT and Lula, and opened up a window of opportunity for Bolsonaro’s anti-system discourse of disillusionment and institutional contestation.

Figure 2: GDP growth in Brazil (percentage change compared to the previous period), source: OECD.Stat https://stats.oecd.org/viewhtml.aspx?datasetcode=EO111_INTERNET&lang=en# and unemployment in Brazil (total, in percentage of total labor force), source: The World Bank Data: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS?end=2021&locations=BR&start=2000

Lula’s corruption charges, which resulted in his imprisonment in 2019, were annulled in 2021 after members of the judiciary were called into question and found to be biased. Since then, Lula has sought to secure his political rehabilitation through a discourse of hope, pacification, and unity. In contrast to Bolsonaro, Lula is able to rely on his background in the PT party. He enjoys the citizens’ trust as he can refer to the socioeconomic successes achieved during his past terms of office. By selecting Geraldo Alckmin, a center-right politician with a more conservative profile, as a candidate for the office of vice president, Lula is seeking to demonstrate his moderate approach.

Lula’s government agenda for the presidency in 2023–202616 reaffirms the role of the state as an instigator of economic and social development, including, inter alia, the continuation of cash transfer programs and a review of the labor law in order to foster social protection schemes. In terms of economic policy, Lula seeks a revision of the tax system coupled with wealth tax, as well as the cancellation of the cap on state spending. Besides this, he opposes the privatization of state enterprises, and his program calls for strengthened environmental protection, thus countering environmental crimes.

Election Scenarios

The preelection polls showed a relatively stable scenario with Lula clearly ahead of Bolsonaro. According to the Estadão poll aggregator17 on September 15, 44 percent of the population intend to vote for Lula, against 33 percent for Bolsonaro; the other candidates account for about 12 percent combined. In the second round, most of the votes tend to migrate to Lula, who would win 51 percent against the 38 percent support for Bolsonaro. However, Brazil’s future may not only be shaped by the actual election results. As recent developments indicate, alternative scenarios are conceivable, four of which will be outlined in the following.

First, before the elections actually take place, Bolsonaro may attempt to postpone them.18 Given that the first round also involves the election of federal deputies, governors, and senators seeking to retain their offices, it could be surmised that Bolsonaro will play the contestation card in the second round,19 which is scheduled for October 30, 2022. However, this scenario seems rather improbable because it would require an extraordinary event or social turmoil as a pretext to establish a state of exception.

In the second scenario, in which the elections take place as foreseen and Lula emerges victorious, Bolsonaro may claim election fraud and refuse to hand over the presidential sash. The ideological and discursive proximity of Bolsonaro and Donald Trump raises the concern that Brazil will face a democratic crisis as in the US, manifested in Trump’s rejection of his electoral defeat and the attack on the U.S. Capitol in January 2021. In Trump-like fashion, Bolsonaro has stated several times that “only God will oust me”,20 suggesting that he is paving the way for a coup. However, it has been argued that any action from the armed forces is rather unlikely,21 and Bolsonaro has been said to lack the support22 required to carry out a conventional coup. Still, the military will be reluctant to cede the positions and power gained through its symbiosis with Bolsonaro. Instead of staging a coup, Bolsonaro is more likely to engage in fueling the agitation23 of the public. In an artificially created climate of mistrust, turmoil, and violence, his institutional and systemic contestation will gain traction more easily. Signaling a desire for confrontation, one of Bolsonaro’s sons has called on gun owners to volunteer for his father’s campaign.24 The increasing proneness to violence among voters,25 including toward the presidential candidates,26 threatens to go beyond rhetoric in the weeks to come.

In the third scenario, a peaceful handover of power from Bolsonaro to Lula takes place, which may be regarded as the most desirable outcome overall. Lula will still be confronted with the challenges of governing an economically and institutionally weakened country in the face of strong distrust among a significant part of the population. He will struggle to deal with a Congress accustomed to trading support for large parts of the budget. All indicators point toward Lula heading a more centrist government to guarantee a coalition, given that the country, which is now more polarized, is less supportive of a leftist agenda than in the past. Although Lula has been welcomed by many, resentment about the PT’s past performance, especially the corruption scandals, still prevails. In the meantime, Bolsonaro and his many allies can be expected to work toward a comeback in the 2026 elections, as the far right has undeniably become an established political actor.

The fourth scenario is Bolsonaro’s reelection. The likelihood of a second term for Bolsonaro largely hinges on his capacity to maintain both the mobilization of his supporters and the institutional backing by the armed forces and further pro-Bolsonaro groups such as the evangelicals. Given the absence of substantial alternatives, Bolsonaro may win the votes of those who are against Lula, believing the long-established narrative that the latter will introduce a communist regime à la Venezuela. Bolsonaro’s reelection would imply the continuation of instability and institutional insecurity, with more advances over the legislative and judiciary powers and a propensity toward arbitrariness with the endorsement of the voters. He has never hidden his coup tendencies, his attacks on democratic legality, and his opposition toward the institutional system. Currently, there is no indication that his second mandate would involve a more moderate approach. Instead, Bolsonaro is expected to keep encroaching on and undermining institutions as well as to seek absolute power for the executive. For instance, he may try to control the Supreme Court through compulsory retirement of elderly judges and by expanding the number of judges he can appoint, thus ensuring a majority.

Conclusion

The 2022 presidential elections are pivotal for the resilience of Brazil’s democracy, where several contrasting scenarios are still possible and the events unfolding in the coming weeks will have long-term repercussions and fundamental institutional impact. Any attempts by Bolsonaro and his allies to either prevent the elections ex ante or reject the results ex post would result in extreme instability and unprecedented social upheaval, with a serious risk of political violence. Whoever wins will need to deal with a country that has been institutionally weakened by successive attacks and politically fractured over the course of the last decade. The downward spiral that Brazilian democracy has experienced in the last few years facilitated and culminated in the current situation, which is proving so critical for the country’s future. Compensation for or repair of the damage inflicted on the democratic system will largely hinge on political will.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)

Ariadne Natal

Latest posts by Ariadne Natal (see all)

- Breaking the Cycle or Maintaining Police Lethality: The Challenge for Brazil under Lula’s Government - 31. Oktober 2024

- Democracy on the Razor’s Edge: The 2022 Presidential Elections in Brazil - 19. September 2022

- Bolsonaro gunning at Brazilian democracy - 3. September 2021

Download (pdf):

Download (pdf):