The French Paradox: Risks to European Defence Harmonisation and Arms Export Control

In his speech on Europe on 25 April 2024, President E. Macron reiterated France’s commitment to building a credible European strategic autonomy. Indeed, the country has one of the most important technological and industrial defence bases in the European Union. However, its often very nationalistic view of the European Union seems to hinder the harmonisation of a common defence strategy and the establishment of a rigorous arms export control system that guarantees the application of international humanitarian law (IHL).

Proponent of a Europe of nation-states, Charles de Gaulle, the first French president of the Fifth Republic, introduced the concept of strategic national autonomy into French foreign policy. To this day, France remains staunchly committed to this philosophy, which emphasises the importance of retaining the capacity to determine its own priorities and make its own decisions in matters of international and security policy, as well as the institutional, political and material resources necessary to implement them. As the world’s second largest exporter of arms, France sees the arms industry as an essential part of its diplomacy to establish itself as an independent actor on the international stage. While France considers the core of European military defence to reside in its alliance with the United States and NATO, it also aspires to be regarded as the vanguard of a ‘European Defence’ by promoting strategic autonomy at the European level. However, France’s Gaullist vision of the Union raises questions whether the nation can truly be regarded as a driving force behind a harmonized European defence industrial strategy.

Against this backdrop, we examine the reciprocal impact of the revised European defence industrial compass on the long-standing French strategic tradition, as well as the institutional tensions and humanitarian risks it raises.

Revitalising the European Defence Industry

The intensity of the war in Ukraine has revealed the structural deficiencies of the European Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB). Despite an increase in the rate of European production, it remains inadequate to meet the requirements of the member states. Since the commencement of hostilities, over three-quarters of the defence equipment procured by member states has been produced outside of Europe, of this 63% being manufactured in the United States. Furthermore, between 2021 and 2022, only 18% of arms purchases by European states have been conducted in a collaborative manner.

In this context, the European Commission (EC), the EU’s executive arm, is encouraging member states to identify defence projects of common interest and to produce the necessary equipment in Europe. In March 2024, the EC launched the European Defence Industry Strategy (EDIS), first common strategy in the field of defence. It has the objective of increasing the level of cooperative research, development, production, procurement and delivery within the EU. The strategy anticipates that by 2030, at least 50% of member states‘ procurement budgets will be allocated to suppliers based in the EU, and that at least 40% of defence equipment will be procured jointly. To achieve this objective, the strategy’s new legislative initiative, the European Defence Industry Investment Programme (EDIP), will be endowed with €1.5 billion until 2027, notably to provide support for existing financial and regulatory instruments. The EDIP is the subject of negotiations between member states and the European Parliament and is unlikely to enter into force before 2025, as it requires unanimous agreement.

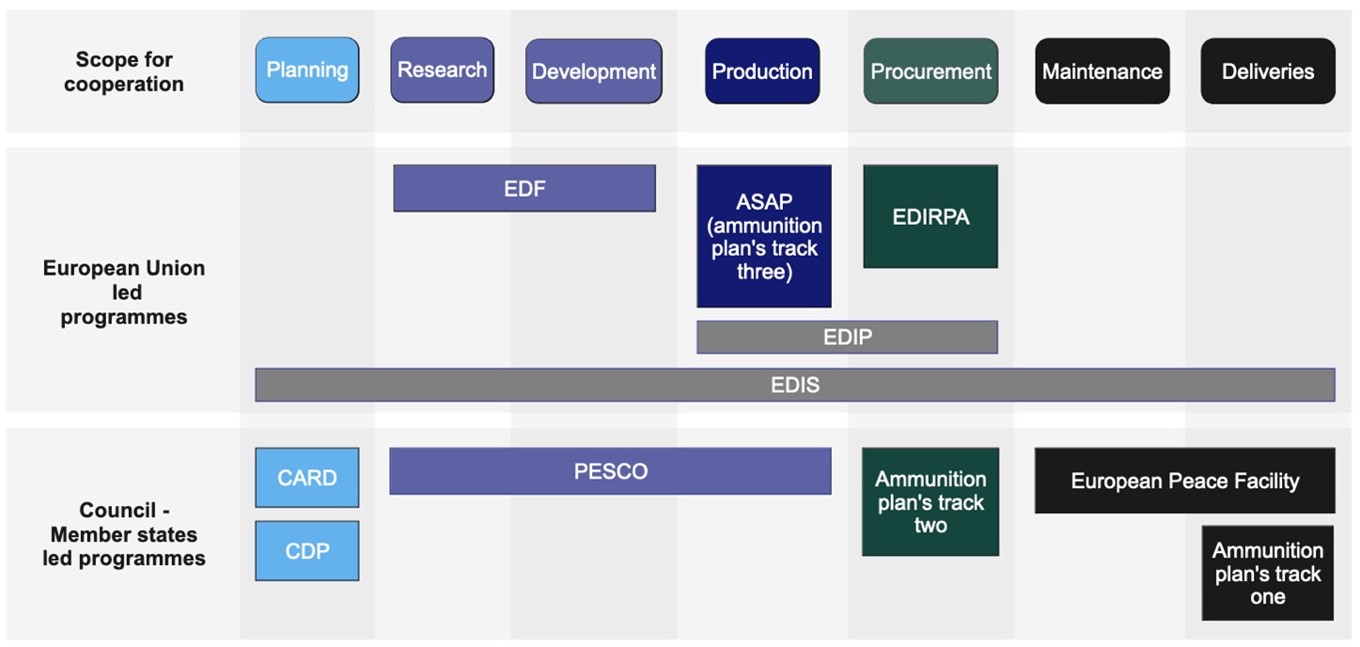

In the context of the European Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), the European Union (EU), already deployed a range of instruments for defence industry cooperation, through various EU institutions.

On the one hand, there are tools that are managed inter-governmentally, directly by the member states. The Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD) facilitates the synchronisation of national defence planning cycles, while the Capability Development Plan (CDP) defines priorities. The Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), initially intended to concern only a small group of EU member states, now enables member states to manage over 68 defence projects in the field of research, development and production. In the area of arm deliveries, the EU provides the framework for the European Peace Facility (EPF), an off-budget fund that allows EU countries to transfer military support to third countries. The European Council, comprised of the heads of state or government of each member state, the European External Action Service (EEAS), EU’s diplomatic service and the European Defence Agency (EDA), a specialised agency comprising experts, are involved in the implementation process of these programmes.

On the other hand, there are instruments that are directly led by the European Union, via the European Commission (EC). The European Defence Fund (EDF) provides financial assistance to member states for research and development. In the wake of the Russian aggression in Ukraine, the Act on Support for Ammunition Production (ASAP) has been implemented in order to enhance the capacity for the production of ammunition. The Common Procurement Act (EDIRPA) facilitates the acquisition of the most urgently needed defence products. Given the complexity of negotiating these programmes, an Ammunition plan was implemented in February 2023 to address Ukraine’s pressing needs: it encompassed accelerated production (ASAP), parallel supply with EDIRPA, and delivery through the EPF. The new European defence industrial compass seeks to harmonise all these different programmes.

France is particularly affected by this new common strategy, as a large part of its defence industry has been integrated into trans-European industry. Compared to other European countries, the French defence industry is of vital importance to French industry as a whole. A significant proportion of the production undertaken by the Airbus Group, Europe’s largest arms manufacturer, is carried out in France. A multitude of smaller French companies also manufacture components for integration into military systems produced by other major French companies, including Nexter and Safran. In 2014, the defence industry employed 500,000 people directly and generated 1,200,000 indirect jobs in Europe, more than a quarter of them in France.

French Ambivalences in Shaping EU Defence Cooperation Policies

France’s position on the European defence industry is influenced by complex tensions between various European companies, member states and institutions. Rather than being the result of a desire for collective action, the integration of the European defence industry appears to be the result of member states‘ perceptions of how they can use the EU to serve the long-term national interests of their companies. In France, this nationalistic approach is particularly strong.

The French government and its representatives are in agreement with the European Commission’s (EC) desire to construct a geopolitical Europe, namely a Europe unified in its foreign and security policy. In 2016, France and Germany capitalised on the Brexit context to reactivate the idea of a Europe of defence. Today, France advocates for the reinforcement of the European Defence Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB). In the field of research and development, France played a pivotal role in the establishment of the European Defence Fund (EDF) and actively encouraged its companies to participate. In 2021, France was the second largest beneficiary country, with 126 companies participating.

However, France is adamant that the direction of the defence industry should remain shared between the EC, the European Defence Agency (EDA) and the member states. The country has historically been sceptical of the EC’s approach to defence matters, questioning its capacity and tendency to regulate the market in an overly liberalised manner according to the internal market competition rules. Regarding EDF, the tendering method is not universally accepted by French companies. They contend that the EC is ill-equipped to select the most crucial projects and to financially support them over several years. A preference for non-competition would entail that member states co-fund French projects and purchase the end products. While smaller European countries favour financing small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), France prefers to directly finance projects from its major national companies.

With regard to production and supply, France expressed opposition to the prioritisation of certain urgent munitions that were included in the European Commission’s initial draft of the Act in Support of Ammunition Production (ASAP). Similarly, the EU encountered significant challenges in persuading France to participate in a joint purchase of weapons for Ukraine via the Common Procurement Act (EDIRPA). Today, the nation has already demonstrated its reservations about the new European Defence Industrial Programme (EDIP). The country is in favour of a larger financial envelope. However, it refuses to allow European funds to be used for the benefit of foreign companies, especially in the United States.

More generally, France has consistently prioritised European Defence Agency (EDA) initiatives over EC initiatives. This intergovernmental agency affords France greater control over decisions. Consequently, France is more involved in PESCO, which adheres to the principle of differentiated European defence integration and would like to bring it closer to the European Defence Fund (EDF).

The Humanitarian Risks of France’s Reluctance to Control Arms Exports

The production of large quantities of military equipment in the European defence industry raises further concerns, including the issue of exporting arms to third countries which are not members of EU, NATO or other partner states. While European initiatives have recently concentrated on arms exports to Ukraine, industrialists have lobbied for increased export opportunities to other third countries to sustain industrial capacities, reduce costs and improve competitiveness. In light of the shift towards a buyer’s market in the arms industry, states importing arms have gained leverage in negotiating contracts. This presents the risk of an arms system that is less internationally controllable, with arms and technology transfers that may be used in conflictual regions for internal repression or international aggression. While not always the case, arms exports to these regions become problematic when there is a systematic violation of International Humanitarian Law (IHL), with civilians as the first victims.

While the export of arms within the EU remains the responsibility of member states, the Union has enhanced cooperation and information exchange through various regulatory instruments, notably the 2008 Common Position. In 2014, European states also ratified the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT). Article 6 of the treaty stipulates that a State Party shall not authorize any transfer of arms if it has knowledge that the arms would be used to commit IHL violations. A consensus within the European Council may facilitate the implementation of embargoes with the objective of stopping arms exports to specific third countries. However, these regulatory frameworks are contingent upon their transposition into national law and are impeded by political divergences between states. In the context of Yemen’s conflict, a number of northern countries (the Netherlands, Finland and Norway) have made commitments to cease supplying arms to the Saudi-led coalition, which has been responsible for IHL violations. These commitments have proven challenging to fulfil, largely due to existing industrial contracts and joint arms projects with countries that do not endorse embargoes, such as the United Kingdom and France. Yet, the recently adopted European defence strategy avoids any commitment to export controls, although it does recognize the inherent risks involved. While the EC is in favour of consolidating disparate national export regimes, some French companies are already opposed to additional EU regulations.

France attaches considerable significance to the role of arms exports in its foreign policy, given the pivotal role these exports play in its national economy. Its objective is to increase exports within the EU by promoting the ‘Buy European’ policy. Nevertheless, Europe accounts for a relatively modest proportion of French arms exports. In 2022, Europe will account for only 23% of French exports, a figure that places it behind the Middle East. France’s economic dependence on a diverse range of third countries, in the absence of a coherent strategic policy, also gives rise to security risks for France and the EU.

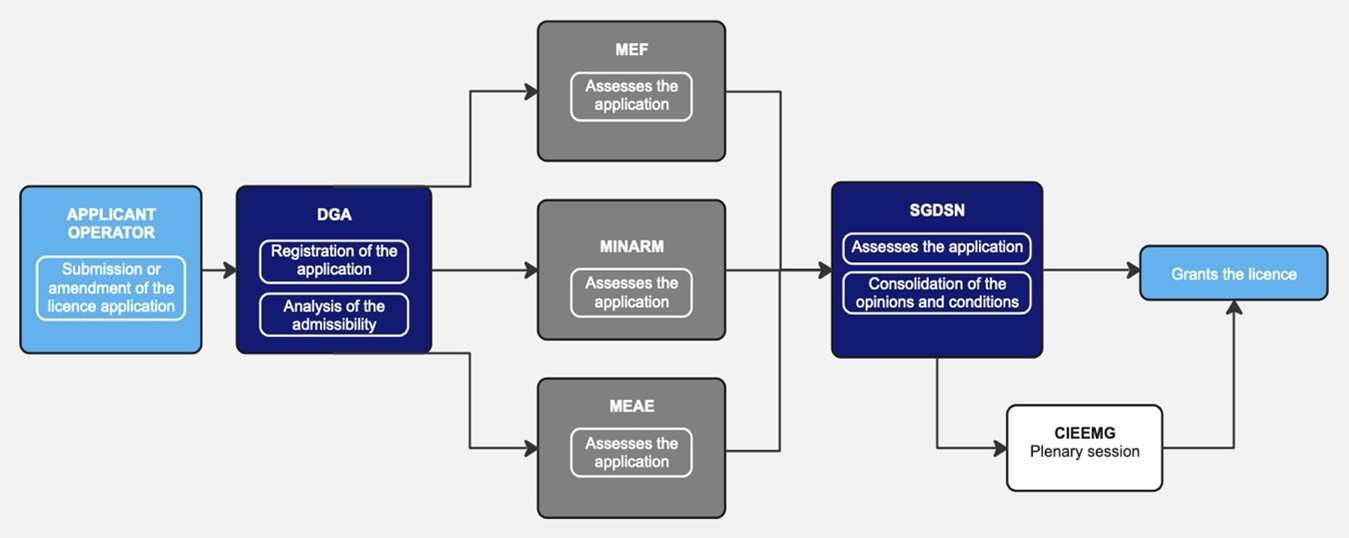

In France, arms trading is prohibited unless authorised by the government. Any French company wishing to export war material must apply for an export licence from the Direction Générale de l’Armement (DGA) before entering into negotiations with the buyer. The DGA then forwards the application to the Commission interministérielle pour l’étude des exportations de matériels de guerre (CIEEMG). This commission is under the authority of the Prime Minister. The decision to grant a licence is based on a case-by-case assessment carried out by the four voting members of the CIEEMG: the Ministry of European and Foreign Affairs (MEAE), the Ministry of the Economy (MEF), the Ministry of the Armed Forces (MINARM) and the General Secretariat for Defence and National Security (SGDSN). The Commission’s assessment is based on criteria defined at international and European level, in particular the EU Common Position and the ATT. In addition, the Comité ministériel de contrôle a posteriori (CMCAP) ensures that the licences issued are complied with.

France has the capacity to produce a range of high-tech military goods. However, due to its reliance on exports, authorities tend to expand their export policy in conflict regions while imposing fewer conditions. A number of non-governmental organisations (NGOs), investigative media outlets and members of parliament have expressed concerns about France’s compliance with international law, citing a lack of transparency, rigour and control in its export procedures. Although the ATT has been ratified by law, the established criteria for arms exports have not been transposed into national law or an implementing administrative act. Nor have the Common Position criteria been implemented. Judicial control is also impeded by the assumption that arms licences are government acts relating to external security, that cannot be challenged in court. Despite the government’s assertions regarding the annual publication of a report on arms exports to the Parliament, public debate is all the more hampered by the classification of executive discussions as confidential in the area of national defence. Thus, in contrast to other European parliamentary regimes, the executive branch of the Fifth Republic retains exclusive authority over arms exports, with minimal institutional oversight.

Conclusion

France, major player in the European defence industry, appears as an ambivalent partner, hesitant to cede as much authority to the Union as might be expected while also reluctant to strengthen arms export controls.

Yet, as the arms industry expands and conflicts in Europe’s neighbourhood persist, the necessity for a common European policy becomes urgent. While France may need to reconsider its national strategy and legislation, the European Commission must demonstrate its ability to unite member states around a coherent, harmonized European Defence Industry Programme with a stronger arms exports policy to effectively apply International Humanitarian Law at the European level.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)

Bleuenn Guillouard

Latest posts by Bleuenn Guillouard (see all)

Latest posts by Simone Wisotzki (see all)

- 25 Years of UNSCR 1325 on Women, Peace and Security (WPS): Birthday Party or Funeral? - 17. Juli 2025

- 25 Years of Women, Peace and Security: Between Promises, Backlash, and Feminist Reimagining - 15. Juli 2025

- Europe’s Defence Dilemma: Rising Militarization Amidst Industrial Fragmentation and Weak Export Controls - 2. April 2025