Endangered Future: Yezidis in Post-Genocide Iraq and the Need for International Support

As the international memory of ISIS’ genocide against the Yezidi population of Şengal in Northern Iraq recedes, its victims have been left to languish increasingly hopelessly, in refugee camps with little realistic prospect of returning to their homes. Tens of thousands of displaced Yezidis remain dispersed across Northern Iraq, hundreds of kidnapped Yezidi girls and women are unaccounted for and the fates of many of their male relatives unknown. In the short term, there is an urgent need for international protection from further attacks, the recognition of a political status for Şengal and immediate aid for refugee camps to create the conditions for Yezidi genocide survivors to return, resettle and gain a sense of political stability and empowerment.

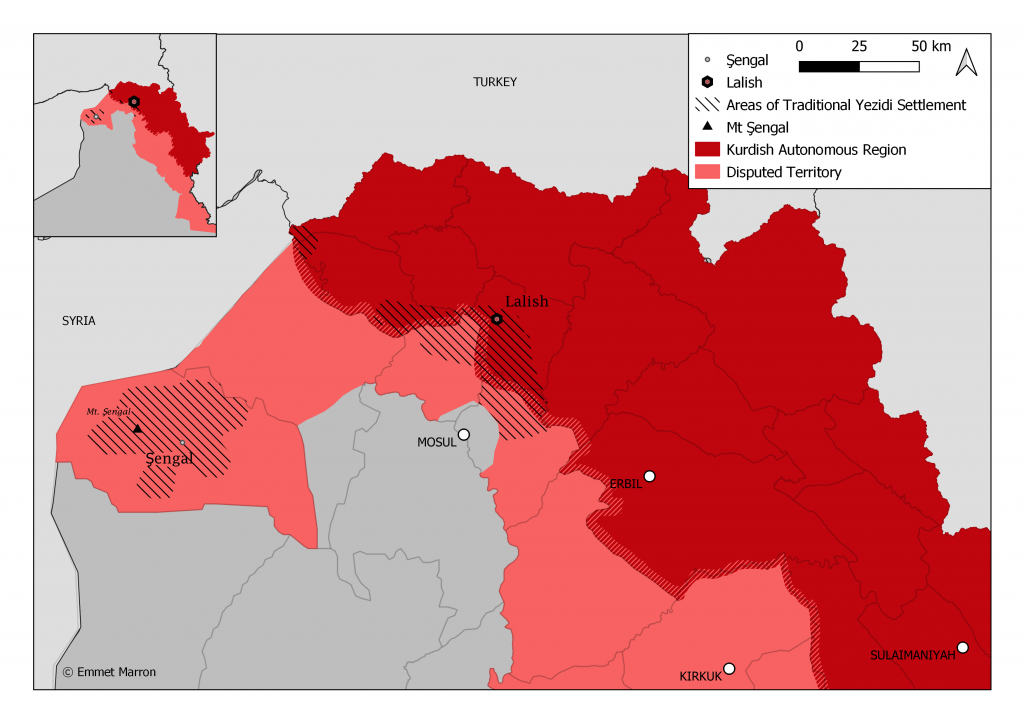

At the peak of ISIS’ military power in August 2014, shortly after it seized the northern Iraqi city of Mosul, its forces swept northwards into the Yezidi territories of Şengal (Sinjar in Arabic). Kurdish Regional Government peshmerga forces presented no military opposition, before fleeing in disarray, leaving the local Yezidi population defenceless. Precise statistics regarding what subsequently occurred remain unclear: it is estimated that around 7,000 men and boys were immediately murdered, 5,000 young women and girls kidnapped, sold as slaves and subjected to mass rape. Surviving children were separated from their mothers, forcibly converted and subjected to ISIS indoctrination. Those that managed to escape the onslaught were forced to seek immediate refuge in inhospitable mountainous areas of Şengal, risking starvation or capture by ISIS forces. Yezidis trapped on Mount Şengal could not be rescued until PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) guerrilla units and Kurdish forces affiliated to the PYD (Democratic Union Party) in Northern Syria repelled ISIS forces and opened a safe corridor. The international community struggled to provide immediate humanitarian assistance to the displaced civilians and could not protect them from further ISIS attacks on the ground. As Şengal lies in the territory legally disputed by the central government in Baghdad and the Kurdish regional autonomous government in Erbil, local authorities on both sides were frozen in inaction, leaving Yezidis without protection in the midst and aftermath of the genocidal attacks.

Divided and Disputed Yezidi Territories

A significant challenge to the Yezidi community in Iraq’s recovery is that their traditional homelands are divided between areas east of the river Tigris governed by the Kurdish regional government and the more southerly Şengal area, which lies in Iraq’s disputed territories. These territories are home to a broad array of religious and ethnic minorities, which have been long subject to systematic Arabisation policies before later emerging as a centre of ISIS mobilisation from around 2014. Due to the sanctions that followed a referendum on Kurdish independence in 2017, Kurdish control of the disputed areas, such as Kirkuk and Şengal, was overturned and it was again ruled by Baghdad. Accordingly, Yezidis’ future in Şengal is inextricably intertwined with broader geo-political tensions. Şengal’s Yezidis were dismayed by the failure of the KRG’s (Kurdistan Region of Iraq) peshmerga forces to protect them and by the collaboration of some of their Kurdish neighbours with ISIS forces, reinforcing the age-old perception that Kurdish identity is synonymous with an Islamic Kurdish identity. On the other hand, the fact that so many Yezidis have been given refuge in KRG territories and were rescued by the largely Kurdish forces of the PKK has led many of them to not only acknowledge a dual Kurdish and Yezidi identity but has firmly positioned Yezidis and their needs, in the centre of the discussion of the so-called Kurdish question in the region.

The Yezidi People

Yezidis traditionally have lived across the region that is commonly known as Kurdistan, stretching across Turkey, Iraq and parts of Northern Syria. The population numbers around 550,000. However, historic and ongoing persecution, and forced conversion have forced many to seek exile in the Caucasus and in western Europe, particularly in Germany. With around 150,000 members, Germany is home to the largest Yezidi diaspora community.

The overwhelming majority of Yezidis speak Kurdish as their mother-tongue, with a small majority in Iraq close to Mosul, speaking Arabic due to decades of state enforced Arabisation. As Yezidism lacks a written culture and most of its traditions have been orally transmitted, Yezidis ethnogenesis is highly contested. Derived from a pre-Abrahamic history, it is largely accepted that today’s doctrinal canon originates from a twelfth century Sufi Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir who settled in Lalish in the Kurdish region of Iraq. It is a monotheist religion drawing on Jewish, Christian and other heterogenous Islamic influences present in the region. There is a vigorous internal debate amongst Yezidis, triggered by various political and cultural factors, as to whether Yezidism is not merely a religion but because of the strict practise of endogamy, also an ethno-religious group. Nevertheless, it appears that many Yezidis reconcile their Yezidi faith with a Kurdish ethnic identity. Although, historically in the Ottoman empire, communities were divided and governed according to religious identity, efforts by modern Kurdish nationalist movements seem to have successfully embraced many Yezidis within a non-sectarian Kurdish identity.

Ongoing Consequences of the Genocide

Thousands of displaced Yezidis have endured yet another winter in refugee camps in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRG) and elsewhere. The camps run by the KRG are both underfunded and overcrowded, and the Turkish invasion of Northern Syria led to a renewed influx of around 17,000 refugees from there, thus exacerbating conditions in the KRG camps. Turkey’s invasion has also had a detrimental impact on the security situation in Şengal; renewed activity by an emboldened ISIS in adjoining areas has ensured that many Yezidis are unable to return to their homes. As many thousands of Yezidi menfolk were executed and thousands of women are still in captivity, the labour required to rebuild houses and revive their agricultural lands is simply beyond the capacity of many of the survivors.

Yezidis’ capacity to return is also marred by the mass psychological damage resulting from the genocide. It is estimated that up to 50% of the population is suffering from different forms of traumatic and post-traumatic stress disorders. It has also revived intergenerational memories of the multiple historic genocides against the community. An additional challenge is that ISIS’ genocide techniques were deliberately designed to fracture the Yezidi community. The committal of mass and systematic rape against many Yezidi women has undermined prevailing social norms in the heretofore conservative society where women’s honour was strictly policed. The presence of many children born in this period and the large numbers who survived sexual violence has proved to be an ethical, psychological and practical challenge for the Yezidi community in Iraq. The recriminations of this are felt far beyond those directly affected, also extending to the Yezidi diaspora and elsewhere in Kurdistan.

Germany as an Exception to the Underwhelming International Reaction to the Genocide

While the international community largely failed to mobilise in the aftermath of the genocide, Germany was an exception. The German state is familiar with the challenges faced by Yezidis, it recognised them as a persecuted group (Gruppenverfolgung) in the 1980s and subsequently became a reception country for Yezidis fleeing the conflict between the Turkish state and Kurdish insurgent groups. The Yezidi diaspora community, often with the support of locally based Kurdish diaspora associations in Germany played a significant role in informing the public and raising political awareness. The government of Baden-Württemberg, in cooperation with internationally renowned psychologist and Yezidi expert, Professor Jan Kizilhan, introduced a special visa agreement for Yezidi women and children who had been captured by ISIS. The project began in early 2015 with 1,100 survivors of severe torture and rape, before its scope was subsequently extended to include transcultural training for German doctors, therapists, social workers and interpreters involved in the post-traumatic treatment of Yezidi women and children. While these efforts had more of an urgent short-term character, post-genocide survival is determined by long-term solutions that facilitate (1) the return of Yezidi refugees to their traditional homelands and (2) survivors’ psychological healing.

Currently 300,000 Yezidis live in approx. 20 refugee camps in Iraqi Kurdistan. These numbers grew with the arrival of thousands more refugees after the Turkish invasion of northern Syria in 2019. Although Yezidis are renowned for preserving their distinct traditions in an extremely hostile regional environment for centuries; in an interview with the authors, Professor Kizilhan explained that it is proving difficult for Yezidis to preserve their cultural and religious practices in refugee camps that have become spaces of “cultural deformation”. Given that six years after the genocide, the majority of the Yezidi community continues to live either in refugee camps in the region or in Europe, the ongoing threat of cultural extinction of an ancient religion and people is of fundamental concern.

Demand for Further Support from the International Community

The international community can contribute to a long-term solution for Yezidi survivors of genocide by promoting a political solution that allows Yezidi refugees in Iraq and Europe to return to their traditional homeland. In the medium term, the Yezidi community in the KRG ruled areas require a legal clarification regarding their political status and powers vis-á-vis Erbil, however the situation of Şengal’s Yezidis is more urgent due to their recent traumatisation and precarious living conditions in refugee camps.

An immediate short-term priority should be the assignation by the Iraqi government of a specific legal status for the Şengal region, such as a province or autonomy within the constitutional framework of the Iraqi federal system. This would grant the Yezidi population political recognition, empower it with local self-governance and facilitate participation in the political decision-making processes pertaining to the community. Given that the Yezidis have become a territorially disaggregated community and are in urgent need of secure spaces of cultural and political autonomy, the question of whether this autonomy should be under the control of the Iraqi central or Kurdish regional government can be addressed at a later stage. It could potentially be resolved along with the fate of Yezidis elsewhere in Iraqi Kurdistan, in parallel with the constitutionally mandated referendum (Article 140), initially planned for 2007, designed to determine the political future of Iraq’s disputed territories.

More than five years after ISIS’ onslaught, the lack of any substantial measures, by the Iraqi and Kurdish regional governments as well as by international organisations and regional powers, to facilitate a return of genocide survivors is detrimental to the likelihood of any long-term resolution of Sengal’s trauma. The situation demands an urgent political solution to enable the return of refugees and return is dependent on the question of security. Accordingly, in light of the failure of the Iraqi central government to provide it, there is a necessity for a guarantee of security in Şengal by the international community to allow returning Yezidis to rebuild their homes and resettle without the fear of attack. Professor Kizilhan emphasises that the challenge of a post-genocide solution for survivors, rests upon the efforts of the international community to create and protect a space where Yezidis can survive without the threat of losing their identity. To give a concrete example of the importance of returning to Şengal, he outlined that one of the great challenges in the therapy process was the triggering effect of the Arabic language. According to him, most survivors see the perpetrators’ presence symbolised in the Arabic language. Internationally guaranteed forms of self-governance for survivors of genocide would, therefore, allow refugees to return and rebuild their homelands as safe spaces of existence, as well as being of critical support to the process of post-traumatic therapy and healing. Finally, the building and support of locally governed institutions to provide psychological treatment for Yezidi survivors of genocide and war is but a first step, and it must be followed by the promotion of a political solution that follows the same empowering principle of “helping them to help themselves”. This would foster the conditions that could mitigate the consequences of genocide, such as intergenerational post-traumatic disorders and cultural extinction due to permanent and dispersed displacement from their traditional homelands.

Link: Further Readings

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)

Latest posts by Francis Patrick O'Connor (see all)

- Endangered Future: Yezidis in Post-Genocide Iraq and the Need for International Support - 12. Mai 2020

- Turkey’s Invasion of Northern Syria Has Begun - 10. Oktober 2019

- Far-right terrorism: Academically neglected and understudied - 18. März 2019

Download (pdf):

Download (pdf):