The Political Logic of Violence. The Assassination of Social Leaders in the Context of Authoritarian Local Orders in Colombia

Ever since the conclusion of the peace deal between the Colombian government and FARC guerrilla in late 2016, the number of social leaders murdered has risen sharply – something that even the latest developments surrounding the Covid-19 pandemic have had little bearing on. These acts of violence are frequently attributed to the presence of armed non-state actors and their fight for control over illegal economies. And yet, the situation has an unmistakably political side to it, reflecting the very modus operandi of local authoritarian orders in Colombia. For counterstrategies to be developed, it is crucial to acknowledge the political logic behind the violence.

Lesen Sie dieses PRIF Spotlight auf Deutsch

The exact numbers are disputed, but the trend is clear: since the historical peace agreement between the Colombian government and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) came into effect at the end of 2016, the violence towards social leaders has been on the rise. According to the non-governmental Instituto de Estudios Para el Desarrollo y la Paz (INDEPAZ), the number of social leaders murdered rose from 132 in 2016 to 208 in 2017. In 2018 and 2019, there were 298 and 279 assassinations, respectively, and in the current year (up until 21st October), as many as 237 activists have already been killed.

In Colombia, the term líderes y lideresas sociales encompasses a broad spectrum of non-governmental actors: representatives of local citizens’ committees (Juntas de Acción Comunal), indigenous, Afro-Colombian, and peasant associations, as well as social movements and organizations active in the fields of human rights, land reform, or environmental concerns, among others. The violence is thus directed towards the very people who advocate, particularly at local level, for the concerns and rights of disadvantaged societal groups. The assassinations – and the attacks and threats against social leaders in general – therefore not only go against the fundamental idea of the peace process in itself. In fact, they explicitly undermine the implementation of the 2016 peace accord. In addition to the demobilization and reintegration of the FARC guerrilla, the peace deal expressly paved the way for a series of social and political reforms that seek to build durable peace “from below”, from within the regions affected by the violent conflict themselves, and with the involvement of the local population. It is precisely those who have dedicated themselves to local-level implementation of these reforms that have now become the target of this violence.

The political face of violence towards social leaders

In their attempts to explain the wave of violence towards social leaders, both the government and numerous observers underscore the role played by illegal economies and non-state armed groups. Indeed, in certain marginalized regions, the demobilization of the FARC has led to the expansion of coca cultivation and cocaine production, as well as illegal mining activities. A fragmented spectrum of violent non-state actors is now battling to gain control of the corresponding resources and territory, among them the remaining National Liberation Army guerrillas (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN), diverse splinter FARC factions that evaded demobilization, different successor organizations of the paramilitary groups which were officially disbanded in 2006, and simply criminal organizations. For these groups, local communities and social organizations committed to the protection of land rights or the promotion of alternative development strategies stand in the way of their illegal activities.

According to this analysis, the fundamental problem is the precarious presence of the Colombian state across the breadth and width of the country. Evidently, in parts of the Colombian territory, the state is not in a position to take effective action against the criminal structures and protect its population. Solutions that are put forward are therefore focused on building on existing measures to protect community leaders (body armor, bodyguards etc.), strengthening the presence of government security forces in the affected regions as well as finding more effective ways of combatting illegal structures.

This explanation covers an important part of the phenomenon, and better government protection for social leaders who are under threat is undoubtedly called for. That said, the sole focus on the role played by illegal actors and structures tends to ignore the decidedly political reasons behind the violence towards activists. The perception of violent non-state actors as mere “entrepreneurs” profiting from criminal activities fails to recognize that, in many cases, these groups have close connections with local elites and are an integral part of local socio-political orders. In a recent study published in Spanish, we argue that, at least in part, the acts of violence committed against social leaders can be attributed to the modus operandi of local competitive authoritarian orders. In this sense, the assassination of social leaders can be considered a genuinely political phenomenon, where local elites who see their power threatened by the peace process and the mobilization of (new) socio-political forces respond with targeted violence.

Violent non-state actors, the state, and the formation of local orders

By now, it is widely acknowledged that spaces where the state has a precarious or selective presence are not “ungoverned”. In the context of the Colombian conflict, for instance, a phenomenon that has been extensively documented is how guerrilla organizations and paramilitary groups establish local orders which combine measures of social control with the provision of public goods and services. The relationship to the state varies in these situations. In some cases the state is completely replaced by alternative local authorities; in others there is evidence of a (de facto) division of labor. Sometimes, there is in fact direct cooperation between the violent non-state actors and state institutions and representatives on the local level.

A similar situation can be observed with regard to criminal organizations. Gangs and other organizations involved in drug trafficking and other illegal activities also undertake some of the key tasks of governing local communities, frequently cultivating multifaceted, at times cooperative relations with state actors. At local level, relations between political and criminal actors go beyond the typical “protection” and “impunity” known on illegal markets, with local politicians forming alliances or agreements with criminal groups that they then use to control the population and exercise violence against their political rivals.

Local competitive authoritarianism as a cause of violence

The problem which, in today’s Colombia, is described as the “precarious presence” of the state in the peripheral regions of the country stems from the way in which this state took shape historically. In essence, the central government, or the national elites, delegated the social and political control over marginalized regions to local elites. When it comes to control of these territories, something which goes hand in hand with access to a wide range of resources (land, state finances, illegal resources), non-state armed actors frequently play a pivotal role even today. In some cases, local elites created these non-state armed groups, in others, the violent actors work closely with the elites or have become local elites themselves. In all of these scenarios, however, the use of force by criminal groups at least partially serves the purpose of establishing and maintaining local or regional orders.

As a result, many of Colombia’s municipalities are characterized by a type of political regime which, drawing on Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way’s study on Competitive Authoritarianism, can be described as subnational competitive authoritarianism. Formally speaking, politics in these municipalities adheres to democratic rules – in Colombia, these are established at the national level and cannot be changed by local elites. Thus, there are civil society actors advocating all kinds of claims and grievances, and elections are held in which opposition groups, including social leaders, participate. In reality, however, political competition and thus access to political power is systematically restricted, in particular through informal control mechanisms such as clientelism, co-optation, and, indeed, violence towards political rivals and social challengers – the latter being “outsourced” to non-state armed groups.

The implementation of the 2016 peace accord threatens these local power structures. First, the agreement includes a series of measures (e.g. limited land reform, participatory development planning) which jeopardize the power base and income sources of local elites. Second, the peace process and the promised reforms gave new impetus to the mobilization of a wide range of groups of the population, which in itself poses a threat to local power structures. In this sense, the wave of violence against social leaders since 2016 reflects attempts by local elites to preserve local competitive authoritarian orders in the context of the peace process.

In order to systematically identify the causes of violence towards social leaders, we have statistically analyzed the occurrence and intensity (frequency) of activist assassinations in Colombia’s approximately 1,100 municipalities since 2016. The results, which can only be briefly summarized in this Spotlight, confirm our interpretation, which emphasizes the relationship between illegal structures and political dynamics. Thus, in keeping with the conventional interpretation of violence as an expression of criminal structures and weak state presence, we find that those municipalities with a strong drug economy (indicator: coca cultivation areas) and those where the demobilization of FARC left a power vacuum (indicator: FARC violent presence 2010-2016) have particularly high levels of violence. At the same time, however, a series of indicators substantiate the political logic behind the violence (see figure).

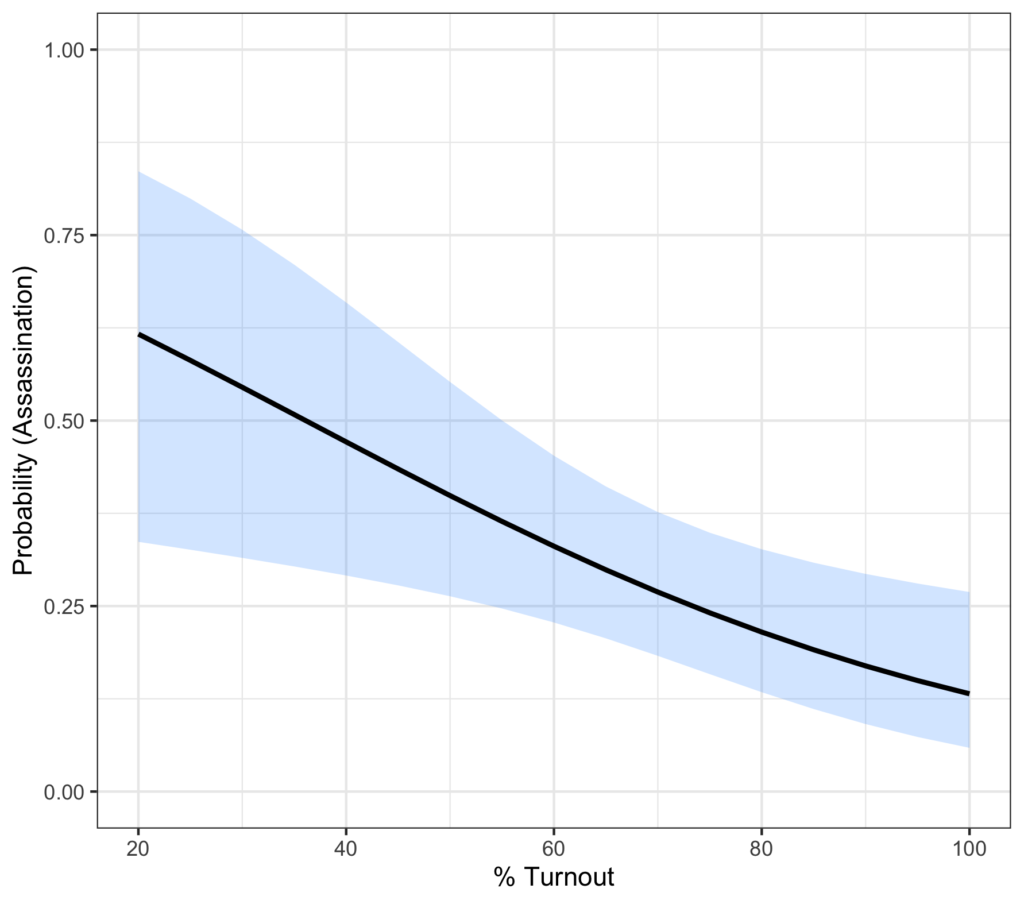

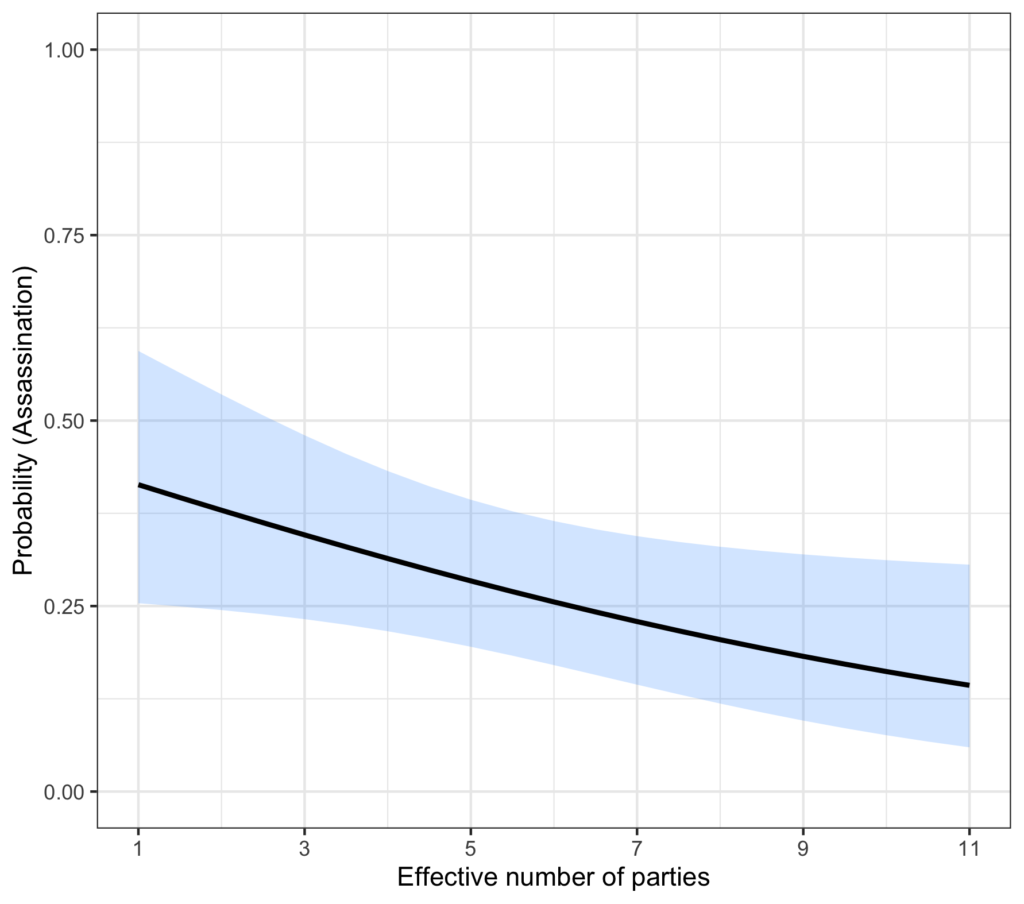

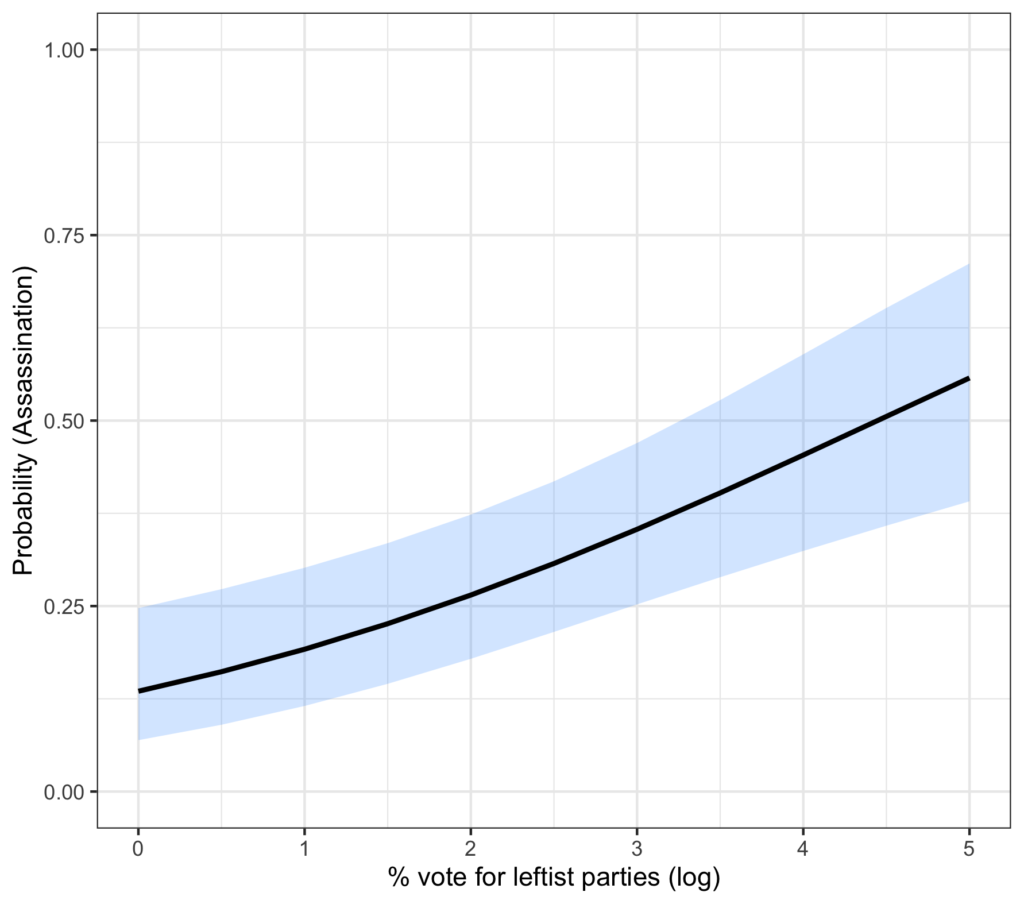

The three graphs illustrate the statistical correlation between the probability of an activist being assassinated in a given municipality and electoral turnout, the effective number of political parties, and the strength of left-wing parties at the local level. Information on the variables and the details of the quantitative analysis can be found in the full study.

On average, municipalities with low electoral turnout prove to be particularly violent – a variable that is influenced by numerous factors, but which in the Colombian context can be read as suggesting de facto restrictions on political participation. The municipalities that are particularly affected by assassinations are, secondly, those where the effective number of parties competing for power is small – in Colombia’s severely fragmented system of political parties this is evidence of restricted competition. Thirdly, an increasing share of the vote going to left-wing parties is also accompanied by more violence towards social leaders. Given the importance of social leaders for the local presence of leftist parties, we interpret their relative power in elections as an indication of the existence of social forces that challenge the dominant elites. Thus, statistically, social leaders are particularly likely to be killed in those municipalities where political power is concentrated and political competition is highly restricted, and/or in which the relative strength of left-wing parties signals at least a potential threat to local elites.

Political implications

If we understand the assassination of social leaders in Colombia as an essentially apolitical problem rooted in criminal structures, the call for “more government” and “more state” would be the solution. However, to the extent that the modus operandi of local political orders is a key factor explaining the violence directed against social leaders, measures have to factor in this decidedly political dimension if they are to have lasting effects. In addition to physically protecting social leaders, then, efforts are needed that aim at democratizing local spaces. In the end, this calls for far-reaching reforms of the political system at the subnational level, which –in the spirit of the 2016 peace agreement – broadens political participation in Colombia’s marginalized regions and drives out the established power structures that link local elites with non-state violent actors.

This PRIF Spotlight is based on a joint research project by the authors, which has been generously supported by the Instituto Colombo-Alemán para la Paz (CAPAZ) and the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung in Colombia (FESCOL). It summarizes the findings of the study “La lógica política de los asesinatos de líderes sociales: Autoritarismo competitivo local y violencia en el posacuerdo” (The political logic behind the assassination of social leaders: Local competitive authoritarianism and violence since the peace accord), which has been published by FESCOL. Free download at: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/la-seguridad/16811.pdf

References and further readings

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)

Juan Albarracín

Latest posts by Juan Albarracín (see all)

Juan Pablo Milanese

Latest posts by Juan Pablo Milanese (see all)

Inge Helena Valencia

Latest posts by Inge Helena Valencia (see all)

Latest posts by Jonas Wolff (see all)

- Freie Fahrt für harte Hand? Ecuadors militärischer Kampf gegen das Verbrechen geht in die zweite Runde - 26. Mai 2025

- Gewalteskalation im Kontext der kolumbianischen Bemühungen um Frieden: Ursachen und Auswirkungen der humanitären Krise in Catatumbo - 4. März 2025

- USAID Facing its End? Likely Consequences for International Democracy Promotion - 7. Februar 2025