Whose Charter? How civil society makes (no) use of the African Democracy Charter

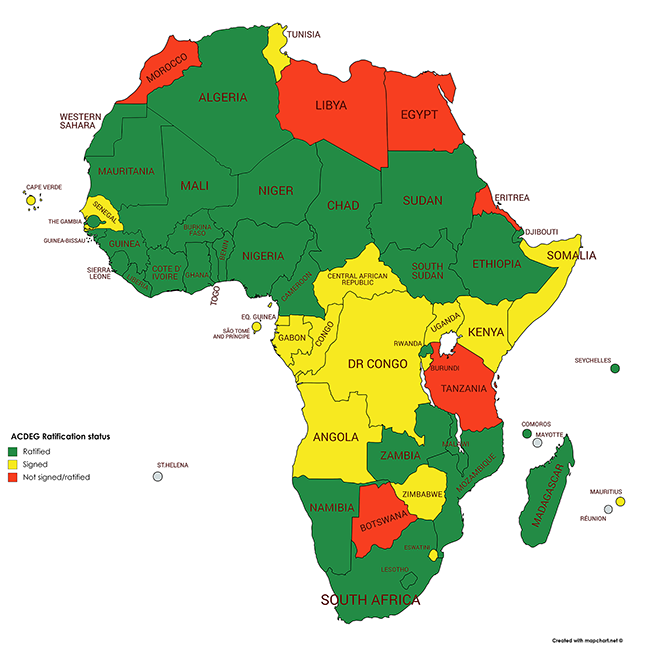

In August 2018, the Peace and Security Council of the African Union (AU) met in order to review the organization’s main legal instrument for the promotion and defense of democratic governance in Africa: the African Charter on Democracy, Elections, and Governance, in short: the AU Charter. Eleven years after its adoption in 2007 and six years after it entered into force in 2012, it was time to ask whether the Charter had made any difference. Yet when assessing the Charter’s effects, policy-makers and analysts too often focus on numbers of ratifications, or the extent to which African states have translated the Charter’s provisions into national law. In this PRIF Spotlight I apply a more micro-perspective and shed light on two instances of political crises – Madagascar in 2009 and Burkina Faso in 2014 – in which the Charter could have been used by national civil society in the struggle for better democratic governance. Such reflections on the everyday use of the AU Charter are rare – yet they provide important knowledge about whether and for whom the Charter can actually make a difference and what policy-makers should do about it. My insights are based on field research and interviews conducted in both countries in 2014 and 2017, respectively.

Hesitant encounters: the Charter in Madagascar

In 2009, the island state of Madagascar was plunged into a political crisis when weeks of public protest in the capital Antananarivo forced President Marc Ravalomanana out of office. The protests were triggered by what was perceived as unjustified enrichment of the political elite, fears over the increasing marketization of land and other natural resources, a lack of confidence in representative institutions, and a general sense of social morale being in a deep crisis. Responding to Ravalomanana’s ouster, the AU and the sub-regional body Southern African Development Community (SADC) intervened in order to restore ‘constitutional order’ through a mediated power-sharing arrangement and elections, a process that lasted for almost five years.

In 2009, Madagascar had neither signed nor ratified the AU Charter. In fact, as with the AU in general, regional norms were little known among the political elite and absent from the wider public debate. So unsurprisingly, the Charter did not play a role in the mobilization of the anti-Ravalomanana protests.

However, with the presence of the AU and SADC, regional norms were gradually introduced into the public debate in Madagascar. Towards the end of the almost five years of transition to constitutional order, a few civil society organizations sought to mobilize public support so that the government, which was to be elected, would finally sign and ratify the AU Charter. One of them was Liberty32, a civic youth organization established in 2010 that aims at promoting democratic norms, youth activism and development. The activists prepared leaflets in Malagasy that summarized the Charter’s main provisions and distributed them across the country. With stands on the weekend in the inner city of Antananarivo, they also sought to collect signatures for a petition demanding that the newly inaugurated President sign the AU Charter. All this took place without any direct contact with or support from the AU, which had opened its liaison office in Antananarivo during the crisis. Yet altogether, the Charter was still a minor item on the activists’ agenda. On the one hand, the turbulent transition to constitutional order had left several issues unaddressed – from reconciliation to socio-economic justice – something which civil society organizations sought to bring to the attention of the new government. As a result, activists gave these issues a much higher priority than the AU Charter, as they had a more immediate effect on the everyday life of many Malagasies. On the other hand, efforts by activists to pressure the new government to ratify the Charter received little societal support: the political elite as well as the wider public remained skeptical about what African regional norms could actually do for them. A frequent and very symbolic response the activists received from passers-by was that the latter refused to sign the petition: they feared that once signed, the Charter – and its anti-coup provision in particular – might take away the right of Malagasies to oust their government if they wanted to get rid of it. Thus, instead of being an instrument in defense of people’s rights, the Charter was perceived as an external constriction to best be avoided.

Still little used: the Charter in Burkina Faso

In Burkina Faso, long-time President Blaise Compaoré was forced into exile in October 2014 following public protests against his attempt to change the constitution and prolong his stay in power. Burkina Faso had signed and ratified the AU Charter in 2010. Unlike in Madagascar, references to the Charter thus played a more important role during the public mobilization of 2014. Yet, altogether, the Charter was and remains largely unknown, even among the country’s political elite.

Long before October 2014, civil society organizations and the political opposition had started to mobilize against Compaoré’s attempts to change the constitution and had sought to gain support from the AU and the sub-regional body Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). In early 2014, the umbrella organization Front Résistance Citoyenne, for instance, which united more than 20 civil society organizations, initiated a diplomatic campaign to attract the attention of AU, ECOWAS, and other international actors. On February 20, in a letter written to then Chairperson of the AU Commission, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, the organization warned that changing the constitution in favor of the incumbent regime would have “disastrous consequences” for the state of democracy, rule of law and social peace in Burkina. They demanded that Dlamini-Zuma “use all her influence” and “contribute on the basis of Article 23 of the African Charter (…) to avert a ‘constitutional coup’ that endangers the principles of democratic alternation through constitutional manipulations.” The same letter was sent to ECOWAS, the EU, UN, the governments of Burkina’s neighbors, and the main international donors. But none of them ever responded. Another letter, sent a few weeks later, also remained unanswered. If and by whom the letter has ever been read remains unknown.

While the Charter thus played a key role in the mobilization of regional and international support, the mobilization of the Burkinabe public in turn drew on other allies: posters with quotations from former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan and then US President Barack Obama – both warning against constitutional manipulations – decorated the streets of Ouagadougou and other larger cities of Burkina Faso. For the Burkinabe civil society, they seemed to be more powerful and more convincing allies than regional legal texts that are little known anyway.

However, the protagonists of the protests later made sure that the Transitional Charter – which served as a roadmap for the post-Compaoré transition – entailed a reference to the AU Charter. With this, they deliberately wanted to emphasize the importance of regional norms, although it remains a hot topic among Burkina’s jurisprudence whether and to what extent regional and continental norms actually supersede national (and constitutional) law.

In sum, as in Madagascar, although the crisis of 2014 served to popularize the Charter in Burkina, it continues to be little known and only a few civil society organizations proactively engage in using and disseminating the Charter. It remains a means in the hands of a very small group of people, often – like the majority of those active in the Front Résistance Citoyenne – in fact lawyers. For them, it seems to be only self-evident to refer to regional and continental doctrines in defense of the rule of law and in search of better governance. Yet the mere fact that in their mobilizations geared towards the broader Burkinabe public regional norms played almost no role at all also underlines the limits of the Charter’s current value as a means for claiming democratic rights and criticizing undemocratic governments.

Civil society and the Charter: Too little known, too little supported

In combination, the two cases highlight common challenges and limits non-state actors face in utilizing the Charter to defend and promote (better) democratic governance. Firstly, they both underline how little the Charter is known at all. This lack of knowledge extends to parts of the political elite. More importantly, however, it applies to both active civil society organizations and the wider public.

Secondly, both cases also underline the limited support local civil society organizations received from the AU once they had started to refer to the Charter. In both cases, the local AU representations did not engage in dialogue with the activists nor did they proactively promote and disseminate the Charter. Moreover, both Malagasy and Burkinabe civil society organizations did not know whom to turn to at the AU Headquarters. Getting in contact with the AU therefore depended to a large extent on informal knowledge and prior experiences of organization members.

Needed: Popularization and active promotion

If the Charter is really supposed to “promote the universal values and principles of democracy”, its popularization among those whose rights it is meant to defend is vital. Calls for ratification and translation into national law – as the AU Peace and Security Council recently did – will not suffice. That Burkinabe civil society was able to make the Charter a guiding document for the transitional period was only possible because the government had actually signed it; a privilege Malagasies did not have. Yet while signing is certainly the key, it is not a panacea. In fact, signature and ratification processes are not necessarily recognized publicly, as the experience of Burkina Faso shows. Thus, signature/ratification as such does not guarantee that the Charter is known and applied. Two strategies are crucial for remedying this state of affairs. Firstly, popularizing the Charter is of key importance in order to tackle the striking knowledge deficit concerning the Charter’s provisions. This could be done through regular radio broadcasting, school curricula, ratification memorial days or creative arts. Experience shows that all this should be linked to specific local/national experiences that demonstrate the Charter’s value in a concrete setting (e.g. around the time of elections). Crucially, popularization efforts should not be directed merely at formal civil society organizations. Rather, public debates are needed on the existence, use and value of the Charter that are not already tied to someone’s claim to represent and speak for ‘the people.’ In addition, popularizing the Charter is not the AU’s task alone, but needs to be pursued simultaneously by various non-state, state and international actors committed to working for better governance and democratic rights. Secondly, the Charter also needs to be actively promoted, especially by AU liaison officers working ‘on the ground’ whose mission mandates should include support and training for civil society organizations in all issue areas covered by the Charter. Without popularization and active promotion, the Charter will not have the intended effect. While democratic politics in many African states are currently experiencing a new dynamism, the AU and its donors should not miss the opportunity to make use of their already existing instruments to support this development.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)

Latest posts by Antonia Witt (see all)

- Cohérence politique pour la paix dans l’engagement allemand au Mali et au Niger ? Cinq recommandations d’action pour le gouvernement allemand - 8. September 2022

- Policy Coherence for Peace in Germany’s Engagement in Mali and Niger? Five Recommendations for Action for the German Government - 8. September 2022

- Friedenspolitische Kohärenz im deutschen Engagement in Mali und Niger? Fünf Handlungsempfehlungen für die Bundesregierung - 8. September 2022