COVID-19 as a Threat to Civic Spaces Around the World

As countries across the globe are desperately trying to control the COVID-19 pandemic, a rapidly increasing number of governments have started to impose severe restrictions on core civic freedoms. Although restrictions are currently necessary to save lives and protect health care from overburdening, these emergency measures must be proportional and strictly limited in time. It is crucial to monitor how restrictions are implemented to prevent governments from using the current crisis to justify new constraints on civic spaces, which have already been shrinking in many places during the last 15 years.

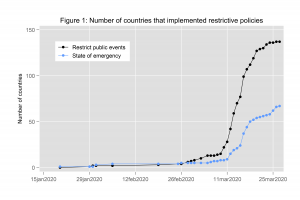

In order to contain the spread of SARS-CoV-2, many countries have entirely suspended freedom of assembly by declaring curfews or similar measures (such as the German “contact ban”). After the Indian government imposed a total lockdown of the country, the Spanish daily El País reported on 25 March 2020 that one third of humanity was now essentially locked up in their homes. As of now, all governments of OECD member states have issued bans on public assemblies and events to various degree and many of them declared a state of emergency, which suspends rights and freedoms guaranteed under a country’s constitution. Figure 1 illustrates the rapid pace with which governments responded to the pandemic with restrictive policies. Within two weeks of March 2020, more than 100 governments banned public events and more than 50 declared a state of emergency.[1]

There is mostly agreement across societies that severe measures that enforce “social distancing” are currently necessary to save the lives of citizens, as otherwise health systems would most certainly collapse. Currently, therefore, also human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch or Amnesty International generally recognize that even drastic restrictions on human rights, including under states of emergency, can be legitimate responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Under international human rights law, which includes “the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health”, governments are in fact obliged to do their best to prevent, treat and control “epidemic, endemic, occupational and other diseases”.

However, as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, the global civil society alliance CIVICUS as well as human rights experts of the United Nations have emphasized, there is a serious risk that governments use emergency measures in order to impose and justify restrictions on civic space that might have mid- to long-term consequences well beyond the current crisis. Measures justified in terms of a human right to health, that is, may unduly and disproportionately restrict civil and political rights to assembly or expression. Unfortunately, we can already observe that pandemics are indeed “fertile breeding grounds for governmental overreach”, as Doug Rutzen and Nikhil Dutta have warned.

Reiterating these warnings, in this blog post, we argue that COVID-19 could indeed give yet another substantial boost to a global trend that has been unfolding since the early 2000s: a wave of restrictions that constrain civil society actors around the globe. In particular, we want to recall the role that another exceptional event with global repercussions had played in the emergence of this wave of civic space restrictions, namely: the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and the subsequent spread of anti-terror measures. This experience suggests that we cannot wait until the pandemic is under control but have to systematically consider potentially lasting consequences of emergency measures and norms right as they are discussed and adopted.

Shrinking Civic Spaces and the Role of 9/11

Since the early 2000s, a growing number of countries across the world have seen the introduction or intensification of all kinds of restrictions that constrain civil society activists and organizations: from administrative barriers that hamper the registration of organizations, to “NGO laws” that delegitimize or limit foreign funding, measures of censorship, surveillance or intimation to the judicial prosecution or physical threatening of civil society organizations and activists.

This phenomenon of shrinking civic spaces is complex and certainly has many sources. Yet, there is little doubt that 9/11 and the subsequent “global war on terror” have played an important role in this story. On the one hand, the US-driven focus on counterterrorism provided governments around the world “with a convenient discourse and justification for tightening their hold over NGOs and their opponents”. On the other hand, international counterterror policies have also directly pushed countries in such a direction. As Thomas Carothers and Saskia Brechenmacher highlighted in a study from 2014, in the wake of 9/11, more than 140 governments “passed new counterterrorism legislation […], often in response to U.S. pressure, UN Security Council resolutions, and the counterterrorism guidelines developed by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF)”. The FATF, established by the G7 in 1989 to combat global money laundering, after 9/11 saw its mandate expanded to terrorist financing. In this context, it adopted Recommendation 8, which identified non-profit organizations as “particularly vulnerable” to be used for the financing of terrorism. In turn, FATF evaluators “endorsed or encouraged” restrictive NGO rules all around the world, from Cambodia and India, Russia and Uzbekistan to Colombia and Paraguay. It took civil society activists until 2016 to get the FATF to revise this contested norm – but, then, “much of the damage was already done”.

Shrinking Civic Spaces in the Current Corona Crisis

Current responses to the COVID-19 pandemic show that the corona crisis is already triggering a dynamic that resembles the effects of 9/11: Some governments appear to be using the pandemic as an opportunity and a justification to impose restrictions that quite obviously serve political purposes. To give but a few particularly noteworthy examples:[2]

The Hungarian government substantially extended its executive power amid the Corona epidemic. On 20 March 2020, the government submitted a bill to the parliament to extend the “state of danger” that had been authorized by government decree on 11 March. The new bill is explicitly entitled “Protection against the Coronavirus”. It essentially allows the government to rule indefinitely by decree and without oversight by the parliament. Additionally, the bill defines the distribution and publication of fake news, rumors, and agitation of the public that interfere with the protective measures of the government as crime punishable with up to five years of prison. Moreover, interference with quarantine and isolation orders are also punishable with prison sentences. Although the bill was rejected by the parliament in the first reading, it was passed in the second reading on March 30 in a procedure that did not require support from opposition MPs.

More generally, we currently witness restrictions of the freedom of speech and extension of surveillance measures in various countries, following the playbook of China’s measures of suppressing information and repressing journalists and whistleblowers. In Thailand, citizens and journalists that criticized the government’s handling of the epidemic faced lawsuits and intimidation from government authorities. Cambodian authorities engage in detention of citizens, especially opposition activists who expressed concern about the coronavirus and criticized the government’s response to it. Similarly, in Malaysia citizens are detained for spreading “fake news” on the coronavirus.

Many governments also currently try to copy China’s tracking efforts of the pandemic, which required citizens to install software applications on their phones that allowed substantial monitoring and surveillance. The governments of Israel and Ecuador already authorized the use of geolocated mobile phone data to track the movement of individuals. Other countries such as Germany, Poland, and the UK are currently planning or debating similar measures of surveillance.

Conclusions

International human rights norms offer useful principles, which should guide governmental responses to the COVID-19 pandemic (see here and here). In addition to being lawful, necessary, proportional and non-discriminatory, governmental restrictions that are imposed as emergency measures have to be strictly limited in duration. This means that all exceptional measures should be adopted for a short-term only and with a clearly defined end, so that they automatically lapse “unless an affirmative action is taken to keep the measures in place”.

Once the Pandora’s Box of unconstrained executive power has been opened it can be difficult to close. Therefore, it is of crucial importance to monitor how restrictions are implemented and retain parliamentary oversight and judicial control. As we are talking here about civic space restrictions, civil society organizations should also be systematically consulted, at the latest when it comes to reviewing and revising current emergency measures.

As the example of the spread of counterterrorism norms after 9/11 shows, these principles are not only relevant when it comes to evaluating emergency measures at the national level of individual countries. Governments and civil society organizations should similarly pay close attention to the ways in which the World Health Organization, the United Nations or the G20 respond to the COVID-19 pandemic by potentially adapting or amending international norms. In this regard, FATF’s Recommendation 8 offers an important experience that should not be repeated.

[1] The data for this figure comes from the COVID-19 Government Measures Dataset by ACAPS. We measured for each country the date when the first restriction of public events occurred and when the state of emergency was declared. Note that the data-collection is ongoing and has not been subject to intensive review. Accordingly, some policies are likely not recorded yet and the exact date of implementation may be inaccurate.

[2] For further information, see also the COVID-19 country reports on the Verfassungsblog.

For more Information on the restriction of Civic Space and the fight against it, you can read the PRIF Report 01/2019 by Jana Baldus et al. „Preventing Civic Space Restrictions. An Exploratory Study of Successful Resistance Against NGO Laws“.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)

Felix Bethke

Latest posts by Felix Bethke (see all)

- Fading Memories of Hope and Empowerment? Why Remembrance of the Peaceful Revolution in Germany Matters and Needs to be Strengthened - 12. Dezember 2025

- Verblassende Erinnerungen der Hoffnung – Warum das Gedenken an die Friedliche Revolution gestärkt werden muss - 8. Dezember 2025

- Back in Business or Never Out? Military Coups and Political Militarization in Sub-Sahara Africa - 28. Dezember 2023

Latest posts by Jonas Wolff (see all)

- Entre la fachada y la perspectiva política: “Regime Change” en el debate sobre la intervención de EE. UU. en Venezuela - 28. Januar 2026

- Between Window Dressing and Political Perspective: Regime Change in the Controversy over the US Intervention in Venezuela - 22. Januar 2026

- Zwischen Feigenblatt und politischer Perspektive: Regime Change in der Kontroverse um die US-Intervention in Venezuela - 19. Januar 2026