Breaking the vicious circle: Can the new Moldovan president Sandu succeed in balancing relations with the EU and Russia?

For the first time in its history, the Republic of Moldova has voted for an openly pro-Western president. Despite facing domestic and international difficulties, the newly elected Moldovan head of state Maia Sandu could manage to solve dire economic problems at home, while securing the support of both Russia and the European Union. This could have longstanding consequences for both the country itself and for all the other states of the common EU-Russian neighborhood.

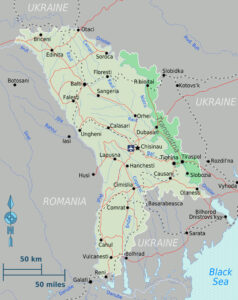

The outcome of the recent presidential elections in the Republic of Moldova was a surprise to many. Maia Sandu, presidential candidate of the Party for Solidarity and Action (PAS), defeated the Socialist incumbent Igor Dodon, taking nearly 58 percent of the vote to Dogon’s 42.25 percent. The country’s first female president has promised to lead the country closer to the European Union and to fight widespread corruption. While her election raises hopes of a more economically well-off Moldova, Sandu also faces serious domestic and international challenges. The Republic of Moldova is one of the poorest countries in Europe and is constantly shaken by corruption scandals.1 According to the World Bank, Moldova has the second lowest GDP in Europe. The country is heavily dependent on remittances from the diaspora both in Russia and the European Union and despite significant international aid, many villages still lack access to electricity, running water, functioning sewage systems, and proper roads. Recent negative trends were compounded by socioeconomic grievances exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, as a result of which the Moldovan economy is expected to suffer even more.2 To cap it all, Moldova is burdened with the most protracted conflict in the post-Soviet space: the frozen conflict in Transnistria.3

The Transnistria conflict

The Transnistria conflict dates back to the end of the Soviet Union and is one of the few remaining “frozen” conflicts in Europe. In 1992, with the support of Russian army, the Russian-speaking territory on the left bank of the Dniester river violently broke away from the newly independent Republic of Moldova. The separatists declared independence, but no country in the world has recognised it. The conflict, which lasted over two months, cost the lives of around 1,000 people. Since the ceasefire in 1992, Transnistria operates as an autonomous region controlled by pro-Russian separatists with the support of Russia. A Moldovan, Russian, Transnistria peacekeeping force was deployed to control the newly established borders. Since then, Transnistria has been supported financially and politically by Russia. Several peace negotiations such as the 5+2 negotiations (OSCE, Russia, Ukraine, Moldova, the Transnistrian region, plus the EU and US as observers) and the Kozak memorandum, which proposed a constitution for a Federal Republic of Moldova, have aimed at a peaceful settlement of the conflict, but with no tangible results.

The Republic is divided between East and West — depending economically and politically on Brussels and Moscow, respectively. Economically, Moldova relies heavily on the European Union, which accounts for 64 percent of the country’s exports. Romania, a country Dodon never visited, is Moldova’s largest trading partner. Russia, on the other hand, which accounts for just 10 percent of Moldovan trade, received over 30 visits from the former president. Moreover, numerous Moldovan companies are on Russia’s embargo list, despite Dodon’s attempts to open the Russian market for them, and the prospects of Moldova entering the Eurasian Economic Union are rather bleak. On a people-to-people level however, Russia remains far more present, as it is still one of the main destinations for Moldovans working abroad.

The ingredients of Sandu’s success

The presidential elections were held on 1 November 2020 with the runoff taking place on 15 November 2020. Three major factors facilitated Maia Sandu’s victory.

First, with the hasty departure of the infamous oligarch and powerbroker Plahotniuc in 2019 following several corruption allegations, the political landscape has become somewhat more diverse. The two most promising candidates both had competitors from within their own camps. Dodon, for example, faced genuine competition from the left-wing political spectrum in the form of Renato Usatîi, the head of the “Our Party”, who accused the ex-president of corruption during the election campaign and who ultimately secured crucial votes from the Dodon camp. Sandu, on the other hand, was challenged by Andrei Nastase, Platform DA, who demanded she withdraw in his favor on several occasions.

Second, Moldova’s compatriots abroad overwhelmingly supported Sandu, with more than 90 percent of their votes going to her in the runoff stage of the election. The diaspora vote constituted around 15 percent of the total vote count. The incumbent Dodon originally tried to level the playing field by opening up more polling stations abroad, especially in Russia where up to 700,000 Moldovan expats live and work, but ultimately this strategy did him more harm than good. After his disastrous diaspora results in the first round (approx. 80 percent for Sandu), Dodon labelled them a “parallel electorate”, which predictably was not well received by swing voters abroad and ended up being the final blow to his reputation. In the runoff, Sandu managed to secure over 260,000 additional votes, both at home and abroad, while Dodon failed to mobilize his supporters for the second round (only around 14,000 Moldovans living in Russia took part in the runoff, for instance, which corresponds to around two percent of all those who were eligible to vote there).

Third, Sandu managed to unite the entire opposition behind her in the most decisive moment. Despite facing a dirty defamation campaign, she unexpectedly won the first election round with 36 percent, which aroused hope and enthusiasm for a potential change. Thereafter, all six eliminated candidates openly supported Sandu during the runoff, including Renato Usatîi who had come third in the first round with 16.9 percent of the vote.

Domestic turbulences and political deadlock

There are high expectations of Maia Sandu when it comes to progressing reform. However, her success in addressing domestic socioeconomic challenges will depend on a political majority in parliament. Unlike many other post-Soviet states, Moldova’s president has rather limited power and is constitutionally balanced by the parliament. However, the current parliament is marked by political turbulence: no party has an absolute majority, coalitions are in flux, and MPs frequently change political party affiliation. This situation prevents the development of a stable environment for sustainable reform and leads to the parliament and the president taking turns in torpedoing each other’s agendas. One of the most scandalous cases in this regard is the judicial reform, which has been blocked by various parties for more than five years now.4

Political party transformation in the Parliament of Moldova

Political party transformation in the Parliament of Moldova: Moldova is a parliamentary republic, which, for a long time, could be best described as a “captured state” where both that state and its institutions were controlled by an oligarch system. Since Plahotniuc’s departure as leader of the PDM (Democratic Party of Moldova) and subsequent ouster of the Sandu government by a motion of no confidence initiated by a pro-Russian coalition in November 2019, the pro-Russian Socialist Party of Moldova (PSRM)-PDM coalition has led the government with 51 of the 101 seats in parliament but is one seat short of an absolute majority. PAS (15 seats), Pro Moldova (14 seats), Platform DA (11 seats), Sor Party (9 seats), and some individual members are represented in the parliament but the pro-European oriented parties PAS and Platform DA fall short of a majority. Most recently, between the two presidential election rounds, Pentru Moldova was created as a new parliamentary platform with members from ProMoldova and the Sor Party.

To break this deadlock, Maia Sandu has already set the process in motion for snap parliamentary elections in the first half of 2021, a move nearly all presidential candidates campaigned for. At the end of December, she already asked the Constitutional Court to dissolve parliament, a request submitted by PAS members of parliament. The situation was ultimately resolved with the voluntary resignation of Prime Minister Ion Chicu whose government stepped down on 23 December 2020, a day before Sandu took office.5

Now, with the path clear for snap elections, Sandu has an excellent chance of implementing the necessary reforms, as long as she gets the required parliamentary majority. But even if that attempt succeeds, the high expectations from all sides will be a heavy burden, making the implementation of the promised changes a challenging task.

Neither East nor West

Although the president’s executive powers lie primarily in the field of foreign policy, Sandu’s foreign policy competencies may in fact still be instrumental in bringing about socioeconomic improvements in the country, especially if she manages to instrumentalize them in the fight against corruption.

Outgoing president Dodon did his best to promote ties with Russia at the expense of relations with all other partners, most prominently Ukraine and Romania. Ultimately, however, he did not manage to develop relations with any of these countries, which significantly hindered the country’s economic development. So, if Sandu aims to eradicate poverty and stimulate Moldova’s economy, she needs the support of all international players, both in the East and West. The fact that she paid official inaugural visits to Ukraine and Romania after having also met with Russian politicians and stakeholders even before officially taking office indicates that she is aware of this delicate balance. Whether Moscow and Brussels are ready to experiment with Moldova remains to be seen, however.

The Kremlin might find it problematic that, during her election campaign, Sandu was quite clear and consistent regarding her orientation towards the West, and the European Union in particular. Among other things, she has called for the withdrawal of the Operational Group of Russian Forces (402 soldiers in total) in Transnistria who purportedly remain there for peacekeeping purposes and to provide security for the Cobasna arms depot. Sandu has called for all munitions to be transported back to Russia, a statement that was ill received in Moscow, with Sergey Lavrov calling it “irresponsible”6.

At the same time, Dodon’s election defeat will not be a serious loss for Moscow. With the departure of the president, Russia might even be able to increase its waning influence in the country under the guise of “system renewal”. This is epitomized by Russia’s pragmatic approach towards the president-elect, whom President Putin promptly congratulated after the results were announced. Already after the first election round, Russia declared its readiness to cooperate with whoever wins the election,7 despite politically (and financially) backing Dodon’s campaign. Russian officials did little to mobilize Moldovan voters in either Russia or Transnistria,8 both traditional pro-Dodon electorates. This might indicate an emergence of a more balanced approach on Russia’s side towards its own neighborhood, which the European Union should recognize and take advantage of.

To do that, however, the West will have to reconsider its wait-and-see approach if it wants to use this opening to make amends with Russia in the common neighborhood. Even though high-ranking politicians like Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel congratulated Sandu and encouraged her “to continue with urgent reforms”, it is far from clear what the Europeans are planning to do with the victory of an openly pro-Western politician in Moldova. The EU had a discouraging experience with Moldova after signing the Association Agreement in 2014, when the country actually voted for a pro-Russian president despite being provided with visa-free access to the Schengen area and benefiting from EU financial assistance programs under the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA). The decline in the rule of law and good governance, the widespread corruption and unpredictable political environment resulted in Brussels recalibrating its assistance to Moldova in 2018. After the change in government in 2019, the EU redirected funds towards more “apolitical” projects, such as general human development, social cohesion and civil society programs.9 This might indicate that European decision-makers have become more pragmatic on the speed of democratic reforms in the country.

Aside from the mechanisms of the decade-old Eastern Partnership, the West rather lacks ideas how to promote its stance in the common neighborhood without provoking Russia at the same time. Given the continuous tensions in relations with Moscow, Western stakeholders should ensure that when they take advantage of Moldova’s new political landscape, they only do so in close cooperation with Russia to avoid aggravating those tensions. Taking into account the Kremlin’s overall negative perception of Eastern Partnership activities in the region as well as its general reluctance to make the first step towards the EU, Moscow is very unlikely to initiate any common initiatives with Brussels. If Europeans are interested in improving the situation on the ground they will therefore have to come up with a genuine proposal, which, among other things should include more realistic conditions for Russian withdrawal from Transnistria. Further, it might encompass funding for projects focusing on the integration of the regions’ economy, politics and society, while keeping close ties with Russia at the same time.

Outlook

Maia Sandu took office on 24 December 2020. A rapid achievement of a much-needed breakthrough in Moldova is not in sight, but the coming months will determine the future path of the country. While it seems very likely that Moldova’s relationship with the West will strengthen again, relations with Moscow will continue to be the essential ingredient for the success of Moldovan domestic and foreign policy efforts. The new president will have to pull off multiple balancing acts by winning the parliamentary elections in an extremely unpredictable environment, on the one hand, and by uniting the international forces in solving the protracted conflict in Transnistria, on the other. Moscow could well play ball if it sees that Sandu is not attempting to make a clean break from Russia and the EU is not actively encouraging such moves. Brussels might also seize the moment and revive its support for Moldova by encouraging the implementation of socioeconomic reforms by providing technical and legal support for the new administration but taking into consideration possible backlash from Russia, especially on trade.

The most important prerequisite for this balancing act is the socioeconomic revival of Moldova, as it has to become attractive for its own citizens (including those in Transnistria) to remain in the country. Yet this is hard to imagine without the international support of both the European Union and Russia, which ultimately, creates a vicious circle. It is up to Maia Sandu to decide where to start, but she should not attempt to play these two big players off against each other. If, however, Sandu recognizes the emerging opportunity and manages to successfully use it to simultaneously solve problems on both sides of this equation, the long-term positive consequences of her achievement, both for the country and the region, will be profound.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)

Mikhail Polianskii

Latest posts by Mikhail Polianskii (see all)

Rebecca Wagner

Latest posts by Rebecca Wagner (see all)

- Securing the Vote: How the US Elections Have Become More Resilient to Threats to Election Integrity - 23. September 2024

- Die Republik Kirgistan im Prozess der Autokratisierung: Steinmeiers Reise nach Zentralasien im Kontext nationaler Prozesse und der deutschen Sicherheitsstrategie - 22. Juni 2023

- Die Parlamentswahlen in Kirgistan: Ein weiteres wichtiges Puzzlestück im erneuten Autokratisierungsprozess? - 25. November 2021