Military cooperation in the Sahel: Much to do to protect civilians

With the emergence of the G5 Sahel cooperation and the creation of a distinct military force – the G5 Sahel Joint Force – military cooperation of the EU in the Sahel has gained new weight. The visit of German Foreign Minister, Heiko Maas, to the region last week together with recent high-level meetings of the G5-Sahel General Secretary, Maman Sambo Sidikou, and Burkina Faso’s President, Roch M. Kaboré, with the German Government highlight this development. The EU, including Germany and France, are key partners to support security and development in the Sahel. However, current developments in combat zones demonstrate the risk of the operating forces to further fuel conflict and accelerate human rights abuses.

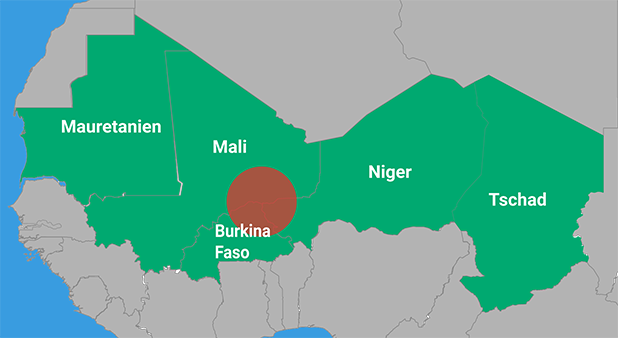

The G5 Sahel Joint Force (G5 Sahel JF) was created by member states of the G5 Sahel group – Mali, Mauretania, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad – in 2017 with the aim to combat terrorism, enhance border control, prevent trafficking and restore state authority as well as to facilitate humanitarian operations and the implementation of development actions. Since then, three operative units of a 5.000 strong regional force are operational in the Liptako-Gourma area, the border area between Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. So far, and albeit the broader aim to enhance development in the Sahel, cooperation of the G5 Sahel member states until today prioritizes a military solution to combat terrorism in the first place.

This has been problematic in various ways, as several elements feed into this very complex, dynamic and high-intensity security environment. A multitude of violent, sometimes extremist, groups are operating in the Sahel, together with a web of transnational criminal networks of arms and drugs trade coupled with a weak presence of state institutions. The identification of targets among the dozens of armed groups in the region and separation from civilians or compliant groups which have signed the Peace Accord remains a delicate issue. Human Rights Watch has documented an increased number of serious human rights abuses of Malian G5 Sahel forces in 2018 committing mistreatments, extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, torture, and arbitrary arrests against men accused of supporting Islamist armed groups. Though not to the extent as in Mali, counterterrorism operations in the northern Sahel administrative region of Burkina Faso in 2017 and 2018 have evoked similar abuses of the military resulting in citizens caught between the fear of security forces and terrorists at the same time.

The EU, and France in particular, has fully supported the initiative from the very beginning. As a key security player in the region it runs three police and military support missions under its Common Security and Defense Policy: EUCAP Sahel Niger, EUCAP Sahel Mali and EUTM Mali. They provide strategic advice and training to the Malian and Nigerien armed forces, police, gendarmerie and National Guard. Followed by the creation of the G5 Sahel JF, the G5 forces and national police were trained in counter terrorism to complement regional aims of the G5 Sahel group. Recently, the EUCAP missions in Mali and Niger have been allowed to provide selective training and capacity building to security actors of other G5 Sahel member states.

Small efforts, major challenges and less promising plans

Both the G5 Sahel countries as well as the EU are aware of the need to build an effective international human rights and humanitarian law compliance framework. 10 Million EUR of a total of 114,7 Mio EUR from the EU’s and member states’ funding channeled through the African Peace Facility is dedicated to this task. Efforts so far have been made in providing basic introductory training to military and police personnel in human rights and the protection of civilians. The G5 Sahel General Secretary has started working on a human rights and international humanitarian law compliance framework for its operations together with the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Further the EUCAP mission in Mali is planning to train national police in order to implement a reporting mechanism of human rights abuses which is supposed to be followed by legal procedures through the judiciary.

Though this idea might work well on paper, reality seems less promising. First, with the police personnel drawn from the same country as the military, it can be questioned whether this leads to independent reporting in practice. Second, access to the judiciary system in these countries is limited in particular for the rural population. As the example of Mali shows, a very limited access to justice beyond its capital Bamako coupled with current (il-)legal practices of jurisdiction provide reason to assume that this idea will be challenging to effectively prevent and follow-up human rights violations. As a result, the judiciary is the state institution that Malians have least confidence in (after political parties which suffer even greater distrust). Further, the reform of the Malian security sector and its forces is lacking behind since the 2000s. Much needed structural reforms and professionalization of the sector are bypassed in favor of urgent capacity building supported by both the Malian government as well as donors. Unless there is a serious political will to professionalize and outweigh corruption within the army, police and the judiciary system together with a clear commitment to structural reforms in the security sector, tracing human rights violations of the military through national police and the justice system will rather lead to dead-ends – in technical and humanitarian terms.

Double victims of violence and a deteriorating economy

Expanding operations of the G5 Sahel JF as envisioned is likely to result in aggravating risks of human rights abuses as well as in further fueling conflicts in an area marked by violence and driven by a complex interplay of extremist and political forces. A recent local study has revealed that people in the Liptako-Gourma region – the border area between Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger – see themselves as double victims caught between violent extremists and their governments’ restrictive security measures. Further, emergency measures such as the ban on motorbikes and pick-up trucks have restricted access to markets with the effect of an increase of local food prices and a higher risk of security risk in the area.

Focusing on a counter-terrorism approach only is incomplete to tackle the many security concerns in the region and in particular from a local angle. According to the recent white book of Mali’s civil society for peace and security, it is not the ‘hard’ insecurity caused by terrorist groups and targeted by military forces but rather banditry, small criminal action and acts of revenge that feed local security concerns within societies. Coupled with the deteriorating socio-economic situation – resulting from a local economy heavily affected by conflict – and a low confidence in the state, particular in the center of Mali, focusing on a military approach only raises questions about its appropriateness and consequences to tackle the local roots and causes of insecurity.

Better complement military engagement

Rather, a more holistic approach to military cooperation in the Sahel is needed. The EU, as well as the German Government, usually refers to the vast humanitarian and development package provided within the Sahel Alliance’s contributions (a total of 8 billion EUR by EU and member states for the period 2014-2020). However, it remains vague how military, humanitarian and development aid are effectively linked and benefit from each other, in particular within recent conflict zones, notably the Liptako-Gourma region. For the case of Mali, simultaneous capacity building in the area of justice and security (first and foremost in Bamako) and the provision of humanitarian aid (primarily to Northern Mali) do not complement the G5 Sahel JF’s operations today. Although national programs have been set up which aim at the areas the G5 Sahel JF is operating in, it is unlikely that these will complement military action in a meaningful way.

Local studies revealed that if security forces lack the population’s trust, a greater presence of the latter do not provide a sense of security, but rather the opposite. In order to gain much needed confidence within the local population, the G5 Joint Force needs to integrate a convenient community engagement approach in its operational planning. Capacity training and logistical support provided by EU training missions should therefore be complemented by measures that aim at building trustful civil-military relations in conflict zones e.g. by eventually adding a more humanitarian role to current military operations. Therefore, a more comprehensive and interlinked implementation of humanitarian and military assistance programs are needed. A better access and enhanced collaboration with residents in conflict zones not only contribute to build confidence, but also to facilitate the collection of sensitive data on conflict dynamics as well as the identification of insurgents living within communities, and thus ultimately contributes to better and more sustainably embed the protection of civilians within military operations.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)

Latest posts by Simone Schnabel (see all)

- Das Ende vom Lied? Der anstehende Abzug von MINUSMA und was das für die deutsche Zusammenarbeit bedeutet - 3. Juli 2023

- Cohérence politique pour la paix dans l’engagement allemand au Mali et au Niger ? Cinq recommandations d’action pour le gouvernement allemand - 8. September 2022

- Policy Coherence for Peace in Germany’s Engagement in Mali and Niger? Five Recommendations for Action for the German Government - 8. September 2022