Is the Worst Yet to Come? Consequences of the COVID-19 Crisis and its Management in the Maghreb

Soon after the global outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, concerns were raised about its potential to exacerbate violent extremism and radicalization. Based on the findings of a EuroMeSCo Policy Study and focusing on the Maghreb states, this Spotlight argues that while the pandemic undoubtedly had serious consequences, there is so far no empirical evidence of a direct “COVID effect” on the activities of violent extremists beyond references to the pandemic in propaganda. In light of this, the article makes the case for broadening the debate to also take more indirect aspects such as the states’ crisis management and the emerging socioeconomic consequences into account.

It is commonly argued that the COVID-19 pandemic is a “crisis intensifier” or a “polypandemic”,2 terms that seem to also hold true for Algeria, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia where the pandemic and its consequences are already beginning to exacerbate preexisting grievances. Many assumed that the pandemic would provide fertile ground for radical groups: rooted in the fact that most extremist groups are generally known for their ability to quickly adapt to and exploit new sociopolitical contexts and digital spaces for their own purposes, it was conjectured that the COVID-19 pandemic might promote violent extremism and radicalization worldwide.3

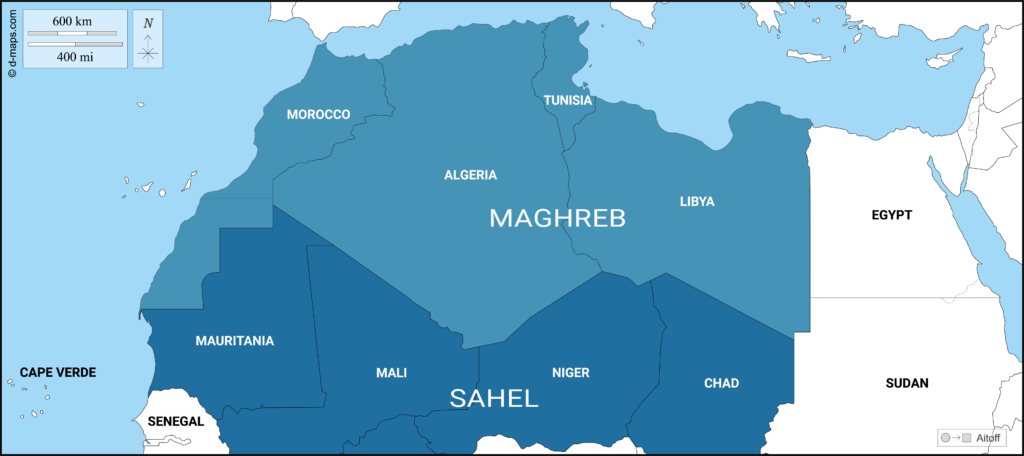

By addressing government responses and policies, as well as the emerging socioeconomic consequences of the pandemic, this Spotlight aims at exploring these dynamics for the Maghreb4 states and calls for temporality to be taken seriously. As part of this analysis, it presents the main findings of a chapter5 within the EuroMeSCo Joint Policy Study “Thriving on Uncertainty: COVID-19-Related Opportunities for Terrorist Groups”, discusses them with regard to more recent dynamics, and provides empirical evidence based on press reports, academic publications, databases, and expert assessments.

Radicalization, Violent Extremism, and the Pandemic in the Maghreb

Soon after the outbreak of the pandemic, both Al-Qaeda and ISIS specifically referred to the virus and the global pandemic in online statements, for instance dubbing it “a soldier of Allah”.6 Due to restrictions in public life, many citizens around the world – including in the Maghreb states – spent much more time at home, presumably on social media, and were thus potentially more exposed to radical content online. Some commentators fear that the resulting self-isolation could “raise the individual vulnerability to extremist narratives”.7 However, while ideologically charged reinterpretations of the virus might represent the most obvious effect of COVID-19 in terms of violent extremism, it has yet to be proven whether it will actually contribute to an increase in the popularity of the respective actors and consequently a rise in radicalization.

Overall, while the rise of ISIS undoubtedly led to an increase in violence and the attractiveness of Jihadist groups, their influence in the Maghreb region has in fact become weaker in recent years.8 This trend also continued during the pandemic, with databases showing that terrorist violence has remained at approximately the same (low) level, which is in line with expert assessments.9 Despite reports of an unsuccessful Jihadist plot in Tunisia – sympathizers were encouraged to cough and sneeze on security forces10 – there is no evidence of radical actors having taken advantage of the pandemic. Yet, the underlying drivers of radicalization remain, making it a worthwhile undertaking to examine the more indirect impacts of the pandemic on future radicalization: specifically, government responses and the pandemic’s socioeconomic consequences.

About the Study

The EuroMeSCo Policy Study “Thriving on Uncertainty: COVID-19-Related Opportunities for Terrorist Groups” was published as part of the EuroMeSCo: Connecting the Dots project, co-funded by the EU and the IEMed. The project contributes to inclusive and evidence-based policymaking by fostering research and recommendations in relation to the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) South priorities, with a focus on economic development, migration, and security. The project aims to connect the dots between diverse stakeholders, as well as between EU Member States, its Southern Neighbours, and across the wider region. It conducts a wide range of research, dialogue, and dissemination activities.

![]()

![]()

COVID-19, Crisis Management in the Maghreb, and Negative Consequences

Like everywhere else in the world, Algeria, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia too have been dealing with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic since spring 2020. It is important to highlight at this juncture that COVID-19 figures should generally be treated with caution, since testing capacity varies significantly from country to country and is certainly “far from universal”, limiting the indicators’ reliability and comparability across countries.11 That said, the figures may at least serve to illustrate some trends.12 Bearing this in mind, while the government imposed several measures to contain the spread of the virus, such as temporarily closing the borders and imposing curfews, recent dynamics in Tunisia give particular reason for concern: not only does this small North African country have the highest infection and death rates in the Maghreb region relative to its population size, but it has also recorded the highest death rate in the whole MENA region,13 with reports about its entire health system being on the brink of collapse.14 The lack of medical infrastructure and healthcare professionals in Tunisia has been an ongoing issue for some years,15 and the pandemic made this problem even more obvious: nationwide, public hospitals are close to full and are facing an alarming shortage of oxygen and intensive care beds.16

As the pandemic escalated over the last year, it was accompanied by several worrying side effects, as it was used by governments as justification for expanding their scope for action and diminishing the rights of civil society throughout the Maghreb region. This first became apparent in the reinforcement of the police and increased surveillance of activists in Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria. Related to this, there have also been worrying reports about restrictions of fundamental freedoms.17 This is particularly evident in the Algerian case: while the emergence of the Hirak movement in 2019 already led to intensified policing, this dynamic reportedly also resulted in a general “criminalization” of dissent,18 with a growing clampdown observed in the context of the recent elections19 as well as the emergence of a new target in the form of lawyers.20 Despite often being seen as an exception in the region, similar dynamics are also observed in Morocco, where repression of journalists, activists, and protesters alike has been on the rise since 2011.21 Moroccan authorities are now said to be “increasingly intolerant of dissent”.22 Moreover, although police brutality has been a problem for years,23 it has represented an ongoing challenge during the pandemic, with protests being held against police violence around Tunisia’s capital, for instance.24 Although these dynamics are obviously not directly caused by the pandemic, but rather reflect an intensification of trends, they link in with findings about a global “shrinking of civic spaces”25 in the context of measures aimed at containing the pandemic.

Interestingly, survey data indicate high levels of public satisfaction with government responses to the pandemic.26 While this is not (yet) reflected in similar levels of trust in the Maghreb governments, it does point to a potentially stabilizing effect of the pandemic, which might allow the governments to externalize the aforementioned negative developments and repression. Overall, interactions with the government and its staff, especially in the form of repression and state violence, are considered to be among the most important drivers of radicalization.27 Even if the future implications remain to be seen, it is already apparent that Maghrebi youths, in particular, are becoming increasingly frustrated, which is potentially and specifically exacerbated by the “lagging and inadequate public services”.28 Consequently, such interaction dynamics seem to be a plausible bridging factor between the pandemic and future radicalization.29

The “Elephant in the Room”: Mounting Socioeconomic Crises

For years now, the Maghreb states have been struggling with severe socioeconomic challenges, In light of this, it is hardly surprising that the clampdown on daily life resulting from COVID-19-related restrictions has hit the Maghreb states particularly hard. Recent estimates already predict a general decline in macroeconomic indicators and demonstrate rising national debt,30 sinking annual growth,31 as well as worsening unemployment rates,32 fueling ongoing debates over infrastructure measures, wages, and overall inflation. This is also evident at the individual level, with opinion polls indicating increased fears of income loss and food insecurity, as well as general economic pessimism.33 While these indicators may provide an overview of the general situation in the region, they certainly do not factor in all the empirical evidence, which points, for instance, to high levels of individual and unreported debt.34 The same holds true regarding the pandemic’s consequences for those working in the informal economy, on which there are naturally no reliable figures. Consequently, the full scope of the pandemic’s socioeconomic consequences can only be assumed.35

Given that socioeconomic grievances act as potential drivers of radicalization,36 it does not seem far-fetched to suggest that radical actors could possibly benefit from the severe socioeconomic crises emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic in the coming years, which could help them in recruiting, mobilizing and gaining legitimacy. In interviews conducted in the context of this study, the pandemic’s socioeconomic consequences have therefore been dubbed the “elephant in the room” as the biggest challenge and most legitimate question regarding the pandemic’s assumed influence on violent extremism and future radicalization. At the same time, it is currently still one of the most difficult issues to assess.

Conclusion and Possible Ways Forward

In sum, there is very little evidence of a direct link between violent extremism and COVID-19 that goes beyond reinterpretation and appropriation for the extremist actors’ own purposes. For the time being, widespread concerns about the pandemic promoting terrorist violence or radicalization in the Maghreb region have not come to fruition. Hence, while the COVID-19 pandemic has certainly proven to be transformative in many ways and has brought dramatic consequences in its wake, it has not promoted new developments, but rather exacerbated preexisting challenges. Researchers and policymakers alike should thus pay close attention to ongoing dynamics and potential mechanisms that might only take full effect in the coming months and years: since the pandemic’s full impact might be yet to come, it is important that we take time seriously37 rather than focus solely on short-term implications.

Consequently, continued commitment to preventing and countering extremism, fostering sustainable economic growth, and taking a stand against human rights violations is decisive. Besides cooperation and exchange of information on equal terms as well as fighting extremists’ online and offline recruitment attempts, European policy efforts must thus involve a continuous willingness to provide sustained economic support and investment. Moreover, recent developments in Tunisia illustrate the urgent need to help contain the pandemic, for instance by sending medical supplies and by considering equitable vaccine distribution as a way to defuse pandemic-related crises. More generally, it is essential to recognize and strengthen the role of young people as agents of change. Granting young people more responsibility, providing them with more opportunities, and ensuring their inclusion in politics and policymaking could, in turn, help reduce widespread frustration – which, on the whole, might be the most effective way of curbing radicalization tendencies.

Notice: The above text as well as the EuroMeSCo Policy Study mentioned were written before the events in Tunisia in July 2021 and therefore do not address any developments arising from them.

Download (pdf): Süß, Clara-Auguste: Is the worst yet to come? Consequences of the COVID-19 crisis and its management in the Maghreb, PRIF Spotlight 11/2021, Frankfurt/M.

Download (pdf): Süß, Clara-Auguste: Is the worst yet to come? Consequences of the COVID-19 crisis and its management in the Maghreb, PRIF Spotlight 11/2021, Frankfurt/M.

Reihen

Ähnliche Beiträge

Schlagwörter

Autor*in(nen)

Clara-Auguste Süß

Latest posts by Clara-Auguste Süß (see all)

- Is the Worst Yet to Come? Consequences of the COVID-19 Crisis and its Management in the Maghreb - 29. Juli 2021

- Who are these “Islamists” everyone talks about?! Why academic struggles over words matter - 3. Dezember 2020

- Macron’s plan for fighting Islamist radicalization – and what Germany and other European countries should and shouldn’t learn from it - 12. Oktober 2020