After the fifth round of the UN-led Constitutional Committee for Syria in January 2021, the UN Special Envoy for Syria, Geir Pederson, eventually announced that they failed to draft a new charter for the Syrian constitution. Further UN-led negotiations were postponed after the Russian-led meeting in Sochi which took place on February 16 and 17. This blog presents the latest developments of the parallel processes of peace talks for Syria, arguing that the United States’ uncertainty in the region is leading to more success of the Russian-led Astana format. This comes not only at the cost of UN-led engagement in Syria but also risks the lives of the population in Idlib as regional counter-terrorism plans are a central issue in the current peace talks.

Since the constitutive meeting in October 2019 in Geneva, the Syrian Constitutional Committee, a United Nations (UN)-facilitated assembly with the aim to reconcile between Syrian conflict parties and to reach a new constitution for Syria, held two rounds before the Covid-19 pandemic hindered their sessions. Both meetings were adhered to structuring the representative bodies and legislative procedures of the negotiations. However, two further sessions in 2020 as well as the last one in 2021, reached nothing but disagreement. Putting pressure on the Russian delegates to assure more cooperation from the Syrian government’s side, UN Special Envoy Pederson noticed that the international community might seek other alternatives if the process was not proceeded. European UN representatives held the Syrian government accountable for the failure of the negotiations. Russia announced another round of the so-called „Astana format“ to “push the peace talks forward“. This parallel negotiations, initiated by Russia together with Iran and Turkey, represent a different concept of peace-making with different means and ends than the UN-led process.

The Parallel Process

In December 2015, as an outcome of the Vienna peace talks and US-Russian Understandings, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 2254 calling for a ceasefire and launching a political process to find a negotiated solution for Syria. The Vienna meetings included European countries, Syria’s neighboring countries, Gulf countries, Russia and the United States with the aim of convincing Syria’s government and rebels to establish a comprehensive negotiation process. Contested by Saudi Arabia, the U.S. also welcomed Iran to participate in the talks in 2015.

Russia, Iran and Turkey also invoked Resolution 2254 as the legal basis for the political process required to solve the Syrian conflict at their first round of Astana talks in January 2017. Initiating the Astana format aimed to sideline further regional powers from the UN-led negotiations, particularly Saudi Arabia and Qatar, who were backing rebel groups in Syria. While the Vienna talks did not produce outcomes on the ground, the Astana talks led to some agreements such as the introduction of de-escalation zones in Idlib, Homs, Eastern Ghouta and Southern Syria.

The Constitutional Committee was formed after a series of negotiations in Geneva in 2018/2019 with the aim to solve the disagreements among different Syrian opposition platforms on the one hand and between the Syrian opposition and government on the other. It constitutes of 150 Syrian delegates who are composed as follows: while 50 delegates represent the government, another 50 represent the opposition and the remaining 50 are coming from civil society delegates invited by the UN. The announcement of the opposition’s 50 delegates was highly controversial and an outcome of additional agreements as the Syrian opposition is split up between three major groups, each of them backed up by another regional power (the so-called “Riyadh-”, “Cairo-” and “Moscow platforms”). The demographic distribution of all 150 delegates highlights not only the underrepresentation of Kurds but also their rather political than technical nature (i.e. specialists in law). This might explain, at least to some degree, the disagreements and latest failure to find a compromise for further negotiations on the Syrian constitution.

The „Astana-15“ meeting, which took place in February 2021 in Sochi, was held with the participation of delegations of the so-called “guarantor countries” Turkey, Russia and Iran besides the Syrian government’s and the opposition’s delegations. Also, UN Special Envoy Pedersen participated in the meetings, along with observers from Iraq, Lebanon, Jordan and Kazakhstan. Russia invited the U.S. to this meeting, too, but the latter rejected the invitation. The two-days meetings discussed the current political and military situation in Syria, stressed the necessity of cooperation of all actors involved in the Constitutional Committee, but most importantly, addressed the future of Idlib. To this day, Idlib is not under control of the Syrian government but controlled by the rebel group HTS which is announced to be the next major tackling point of the Russian-led “coercive peace” approach in Syria.

Russian Coercive Peace and United States’ Long War

The Russian approach towards coercive peace can be traced back to the late 1990s and the conflict in Chechnya where Russia was engaged in ending peace talks with rebels and pursuing a counterinsurgency campaign, accompanied by political moves to promote Russian-loyal Chechens. The Russian military victory against Chechen rebels was consolidated by providing support to Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov.

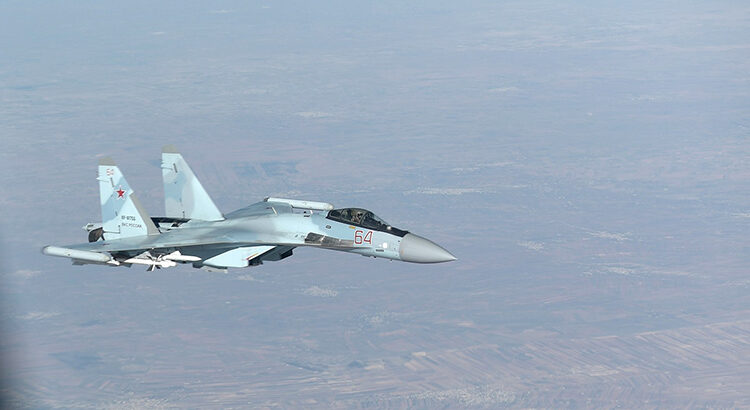

Central to the notion of coercive peace is a hard understanding of state sovereignty – which also needs to be seen in opposition to previous western interventions in the Middle-East and emerging international norms such as the Responsibility To Protect. In fact, Russia has followed this policy of illiberal or coercive peace in Syria, Sudan, Libya, Afghanistan and Central African Republic. In contrast to the concept of liberal institutional peace, Russia’s aim in those interventions is to achieve a negative peace (i.e. the absence of heavy violence) and to install stable governments, without addressing the deeper reasons of the conflict or even a democratization agenda. Obviously, political interests are the main driver for this kind of conflict mediation which is not an exclusive case for the Russian mediation in Syria. The major tactics of this policy in Syria are to use military dominance to enforce local ceasefires or de-escalation zones and to persuade opposition parties to negotiate within the preferred Astana format. Regardless of the establishment of de-escalation zones in 2018, the Russian Air Force supported the Syrian army in proceeding their operations and evacuating Islamists and opposition rebels from two of the de-escalation zones to Idlib.

This kind of Russian engagement in Syria must also been seen in context of the United States’ withdrawal from the Syrian conflict which already started under the Obama administration on the one hand, and the high causalities among civilians caused by the U.S.-led anti-ISIS coalition on the other. Both developments challenge the alleged moral position of U.S.-peacebuilding efforts in contrast to Russian expansionism in Syria. This trend further intensified with the Trump administration’s clear “leave it to the Russians” approach, promising the Americans to quit post-conflict “nation-building business”. However, this approach was somehow contradicted later in course of the Caesar Syrian Civilian Protection Act, based on the horrific photos from Syrian detention centers. The so-called “Caesar photos” were first analyzed in a private report commissioned by the government of Qatar and was made available to the UN and human rights groups since early 2014. Passing the economic sanctions six years after the evidence for mass torture in Syria highlights the role of the U.S. political interests in pursuing human rights norms in the Syrian conflict.

However, pushed by strategic on-the-ground factors, more factions of the Syrian opposition seem to be accepting the Russian approach on coercive peace as the mixture of withdrawal and engaging with sanctions from the United States’ part on the one hand and the U.S. refusal to cooperate in the Russia-led process on the other might suggest an U.S. undetermined long(er) war policy in Syria.

Counter-Terrorism Demands in Astana

Counter-terrorism demands, as articulated in the joint statement of Russia, Turkey and Iran, overshadowed the last round of Astana talks in February 2020 and added one further condition for the Geneva peace talks. It was especially the Russian delegates who were stressing the need to fight, not to negotiate with terrorists in order to help advancing the country’s political process within the framework of the Constitutional Committee. After referring to the unity of Syria, their statement made clear that the next step in the peace process will be to eradicate remaining terrorist groups in Idlib. Until today, Idlib is controlled by the Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS) group which is a merge between the Syrian Al-Qaeda branch Jabhat Al-Nusra and other Sunni militant groups.

Even though the United States did not participate in the latest talks in Astana, the question of Idlib is still relevant to U.S. counter-terrorism policy in Syria and the region. The new Biden Administration is undergoing changes in their list of designated terrorist organizations. Biden reversed the designation of Iran-backed Houthis as a terrorist organization in favor of relieving the humanitarian crisis in Yemen. Similarly, the International Crisis Group suggested doing the same with the HTS in Idlib in order to avoid a humanitarian disaster and deploy HTS in aiding civilians.

Between cooperating with (former) terrorists and cooperation in order to eradicate terrorists, the question of counter-terrorism policies remains determined to both processes of the Syrian peace talks and, most of all, the future of three million civilians living in Idlib. The next military campaign after this round of negotiations in context of the Russian coercive peace approach will most probably be framed as an “anti-terrorism” one. The Syrian and the Russian forces will either have to cooperate with opposition groups in order to eradicate the HTS from Idlib, or would do it more “traditionally”, that means waging an open campaign to recontrol the area. Especially the latter will have a disastrous outcome on Syrian civilians, causing a series of humanitarian crises and waves of forced mobility. Furthermore, it will also have implications for further group dynamics of several militant groups designated as terrorists in the region.