Contrary to popular opinion, extremist communication is not simply based on hatred and calls for violence. While beheading videos or livestreamed shootings may generate attention, displays of violence alone are an insufficient basis for an extremist ideology and claims of legitimacy. Utopian narratives – visions for the perfect society – are an indispensable element of propaganda efforts. Without detailing what one is fighting for, an essential part would be missing from the web of extremist ideological communication. While the last years have seen an increase in narrative campaigns designed to delegitimize extremist ideologies and provide alternative worldviews, pro-democracy narratives struggle with responding to the utopian visions propagated by extremist actors.

Any form of collective action or political ideological campaign must be underpinned by three elements, often referred to as frames: A diagnosis of the problem (what’s wrong?), a prognosis for the future (what do we want to achieve?), and a call to action (why should I be motivated to take part?). Whether one is seeking to overthrow the government in order to reverse multi-culturalism, build a Caliphate, or inspire citizens to take part in cleaning the local park, communicating the problem is insufficient to inspire action. To motivate the audience to act, presenting a vision of improvement and a solution to the problem at hand is essential. People need to know what they are fighting for to find meaning in their actions. Communicating a utopian vision of what a better society will look like and thus providing a greater goal is a stronger motivational drive than simply detailing the problem.

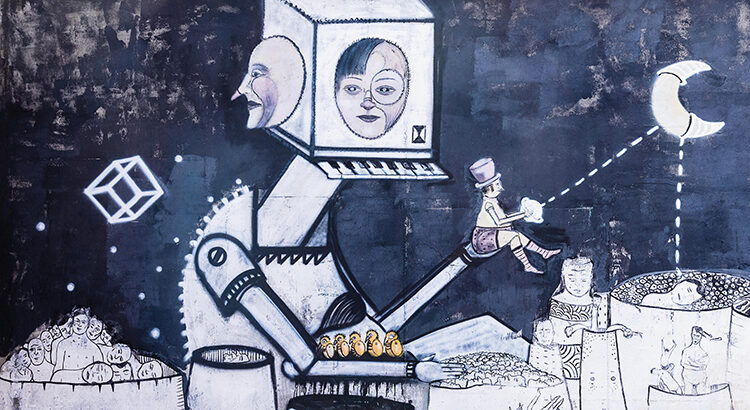

Often, such diagnoses and utopian visions are communicated through ideologically-charged narratives, which promote a particular interpretation of the issue at hand and a set of corresponding values to judge the situation. Such visionary narratives that lay out an ideal future present a much larger part of extremist communication as one may think. The so-called Islamic State (IS), for instance, deliberately engaged in positive messaging of utopian state-building and sketched a perfect utopian society of brothers and sisters in its propaganda campaigns. Narratives of brutality and violence received the most attention from Western media, but it was the narratives that promised a better future, a land of milk and honey, and a peaceful, prosperous, Muslim society that inspired many to travel to Syria and Iraq.

Narrative campaigns defending the status quo

Because narratives are such an important component of extremist communication and are believed to play a part in radicalization processes, the last years have seen an increase in efforts to utilize narrative campaigns as tools for preventing or countering extremism. Such narrative campaigns are aimed at both delegitimizing and deconstructing extremist narratives as well as providing so-called alternative narratives revolving around positive stories of and referrals to democracy, tolerance, and unity. While guidelines and suggestions for the development of such campaigns are manifold, countering extremist narratives seems to come easier than providing positive narratives that may present a real alternative to the utopian visions found in extremist ideologies.

That alternative narratives have trouble to present a believable and exciting prospect for the future may be, as some argue, because “pro-establishment messaging is inherently uncool”. This results in an important advantage for extremists: Individuals may be partially drawn to extremism by the thrill that fighting to change the system and being part of the revolution carries, whereas the mainstream and defense of the status quo may seem unappealing and boring. Worse still, this status quo is often not perceived to be a positive state, but fraught with injustices. Defending it may be seen as justifying discrimination and oppression, the support of ‘corrupt’ elites leading a ‘broken’ system, or as a pathway to alienation from what is just and true. Since the status quo is far removed from an ideal society, narrative campaigns relying on the display of positive aspects of existing conditions may be unable to provide a believable and desirable alternative to extremists’ utopian narratives.

General lack of utopian narratives

However, the issue goes deeper than the perception that the status quo is less than perfect. What Western societies such as Germany are lacking is a truly prognostic element in the societal discourse and a long-term vision for the improvement of society. Where do we want to go? What do we want society to look like in 50 years and how different will that be from what it is today? Aside from continuous economic growth and smaller, specific elements of ‘progress’, where are we headed? What is the big vision, the ideal society we want to build?

Those who believe in liberal democratic values may regard it as imperfect but the best foundation possible for the organization of a modern nation state and society, there is no grand narrative of change and no utopian vision to fight for. The West is currently witnessing the emergence of an anti-utopian age; i.e. the abandonment of the very idea of utopia. If the current system is believed to be the best one possible, one may expect small improvements but no big leaps towards a different organization of society. There cannot be a utopian vision, because the status quo is perceived to be the best we can do. In an anti-utopian age predicated on the idea that Western liberal democracy and the current societal conditions are the beacon of human political achievement, the very idea of revolution may be appealing to those not satisfied with the status quo and longing for a vision to work towards.

Therefore, alternative narrative campaigns struggle to counter extremists’ visions for building a utopian alternative to current social realities, because there is no grand narrative to pit against this element of extremist propaganda. The best such narrative campaigns can do (and are doing) is to acknowledge that the status quo is imperfect, that grievances are real and justified, and suggest an alternative route for dealing with such grievances. The question is whether this will be enough to help individuals channel their revolutionary drives, the longing to build a better future and to achieve far-reaching change to improve the world we live in, into non-violent forms of action.

It is possible that this will not be sufficient. For a holistic approach to countering extremist propaganda, we may need a grand vision of social progress as an alternative. If we do not have one, we are left to counter only part of what makes extremist ideologies and the corresponding narratives appealing, and counter-measures will always be incomplete. This is not an issue that can be solved by a clever campaign from a non-governmental organization but a much broader question pertaining the narratives our societies are built upon: Where are we going? What is our vision? Extremists of all couleurs are currently doing a much better job than mainstream society to answer such questions and communicate them effectively. Engagement with such questions may therefore be essential to navigate the stormy waters of an anti-utopian age generally, and to struggle against the appeal of modern extremisms specifically.