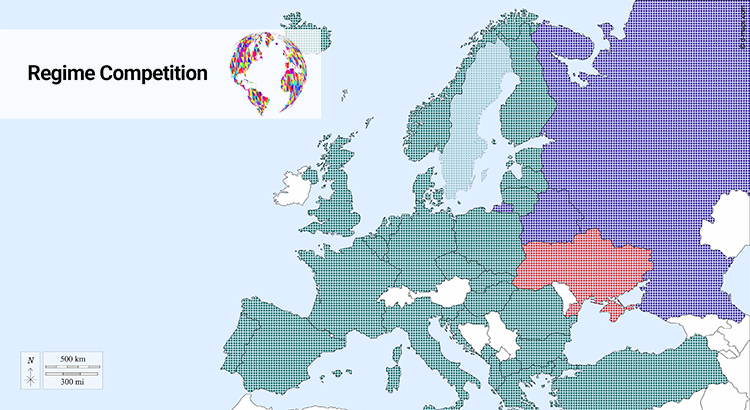

In the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war, and in the wider Russo-Western conflict, both sides compete over international influence as well as over how Ukraine and Russia are governed. While most would agree with this general assessment, prominent scholars like John J. Mearsheimer and others have argued that the West caused these confrontations by aggressively expanding its influence and preferred regime type into Ukraine, thus forcing Russia’s hand. However, while Russia’s perceptions of NATO evidently played a role in its decisions, a recent study finds that Mearsheimer’s arguments are at best incomplete and at worst simply false.

Among Western comentators that put most of the blame for the Russo-Ukrainian conflict on the West, John J. Mearsheimer is arguably the most prominent, with his 2015 lecture on the topic having garnered over 29 million views on YouTube to date. He also put his views in writing, both after the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014 and during the ensuing war in Ukraine’s Donbass [a, b, c] as well as after the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 [d, e].

Russia threatened Ukraine well before 2014

Mearsheimer argues that Ukraine and Western countries formed ever stronger ties with each other, and that this caused legitimate security concerns in Russia, with the result that Russia lashed out against Ukraine in 2014.

However, for this argument to work, Mearsheimer needs to show that Russia had not given Ukraine and the West some sound reasons to align with each other before 2014. In other words: Mearsheimer’s arguments require Russia to be a peaceful and restrained counterpart to the West prior to 2014.

Mearsheimer, however, does not provide us with examples of peaceful and reasonable Russian behavior. Furthermore, several events contradict his view. To begin with, throughout the 1990s and 2000s, Moscow had repeatedly used energy sanctions to force concessions from Kyiv.

Russia had also put significant pressure on Ukraine before 2014. For example, in 2004-05, Russia interfered in the 2004/2005 Presidential Elections in Ukraine, using illicit party and campaign funding, covert operations and fake news operations to help its preferred candidate, Viktor Yanukovych. Russia was, however, unsuccessful. The new ruling coalition, which had been pro-Western to begin with, saw Russia’s interference as yet another reason to push for Ukrainian membership in NATO and the EU.

While there is no proof that Russian elites ever seriously considered taking Ukrainian territory before 2014, Ukraine certainly had reasons to fear this could eventually be the case. For example, in the 1990s, communists and nationalists in the Russian state Duma put significant pressure on President Yeltsin to re-incorporate the Ukrainian peninsula Crimea into Russia.

Signaling that NATO members might be victims to Russian aggression as well, a massive cyberattack originating from Russian territory struck Estonia in 2007 after it had made the decision to remove a Soviet monument from a central square in its capital.

Thus, Russia had given both Ukraine and Western countries specific reasons to worry about its future conduct, thus contributing to the very alignment that Mearsheimer sees as the root of the problem to begin with.

The Ukrainian revolution of 2014: not an anti-Russian coup

According to Mearsheimer (in 2014 and in 2022), and echoed by many, the Ukrainian Revolution of Dignity in early 2014 was a western-sponsored, illegitimate coup that brought to power a small, fervently nationalist and anti-Russian section of Ukrainian society. If this was true, Russia’s subsequent annexation of Crimea and its fomenting of war in Ukraine’s Donbass region could somewhat plausibly be seen as a defensive move to stop an intensely chauvinist movement in its tracks. The actual history of these events, however, is different.

For example, Mearsheimer correctly stresses that Ukraine’s supposedly pro-Russian president Yanukovych, who was swept away by the revolution, had been elected by more or less democratic means in 2010 (having failed in 2004/05). However, Mearsheimer omits crucial facts. From his election up until 2014, Yanukovych increasingly undermined Ukraine’s already frail democratic institutions, restricted liberties, oversaw massive election fraud, and ordered the protest movements on the Maidan to be put down by force. The revolution got rid of an autocrat.

Similarly, Mearsheimer does a poor job at corroborating his allegation that the new Ukrainian government was hyper-nationalist. The only piece of evidence he gives to this effect is the plausible observation that four of its ministers could be argued to come from a fascist background. However, Mearsheimer neglects to mention that there were over twenty ministers total, that one of these ministers resigned after only a month in office, that the other three did not have portfolios connected to the security forces, and that Ukrainians voted these far-right politicians out of office as soon as they had the chance to do so (in the internationally observed presidential elections in May 2014, and in the parliamentary elections in October, both of which were largely assessed to be fair and free).

The other arguments are similarly weak: Mearsheimer alleges that the West “creat[ed]” the crisis, that the 2014 revolution was unpopular among Ukrainians in the country’s South and East, and that the ensuing war in Donbass was a “civil war”, implying at most a very minor role for Russia in this conflict. But he does not corroborate either point systematically, and what little evidence he cites is scattershot, ambiguous and contradicted by other data.

For example, Mearsheimer’s depiction of the Donbass conflict as a mere “civil war” flies in the face of systematic research. Evaluating satellite images, expert interviews and the results of various fact-finding missions, it has long been established that Russia directed and supplied anti-Kyiv forces, often simply funneling Russian soldiers without insignia over the border. Other studies drew on leaked emails from Russian agencies to show how Russian operatives deliberately manufactured the kind of “civil war” that Russian elites publicly claimed to not even be involved in.

NATO policy did not force Russia to invade in 2022

Through Mearsheimer’s arguments runs the theme of the West proactively pursuing unwise policies and Russia having no choice but react to them in the exact way it did. Key is, of course, the allegation that NATO engagement with Ukraine forced Russia’s hand in 2022.

Mearsheimer does not discuss episodes that do not fit his narrative. For example, Western states accepted Yanukovych’s election as Ukrainian president, even though Yanukovych, quite foreseeably, put Ukraine’s NATO aspirations on ice in 2010.

Furthermore, Mearsheimer discusses nowhere how Russian pressure on Ukraine gave both Ukraine and Western countries reason to worry about future Russian conduct and therefore strengthen relations between them, including via NATO.

For example, after the Crimea annexation and the start of the war in Donbass in 2014, many Western countries, including a traditionally reluctant Germany, adopted a much firmer stance against Russia and increased their support for Ukraine. It stands to reason that, without the Russian aggression of 2014, the promise of future NATO membership for Ukraine as issued in the Bucharest summit of 2008 would have remained politically inconsequential, analogous to the elevation of Turkey as an official EU membership candidate in 2005.

Mearsheimer specifically alleges that, in 2021, “Ukraine began moving rapidly toward joining NATO”. One of the few pieces of evidence Mearsheimer cites for this is that “Ukraine’s military also began participating in joint military exercises with NATO forces”. He specifically names the Ukrainian-American-hosted Operation Sea Breeze and the Ukrainian-led Operation Rapid Trident 21. However, Mearsheimer neglects to point out that these operations have long been conducted on an annual basis and that Ukraine had long been part of them—including under the supposedly pro-Russian and anti-NATO president Yanukovych.

While it is true that, by 2021, Ukrainian president Zelenskyy had adopted a more robust policy toward Russia, and that the new US administration under Joe Biden made a point of strengthening ties with Ukraine, it is far from clear if the 30 other member states of NATO would have followed suit (steps to NATO accession require unanimous affirmation by the members).

Again, it was Russia’s aggression that created the very consensus it supposedly had feared. Even though Germany had been reluctant to support Ukraine when Russia amassed troops for an invasion in the winter of 2021/22, it rapidly changed policy once the invasion was underway. NATO support for Ukraine was at a historic high after Russia’s aggression in 2014, and rose even higher after the Russian attack of 2022. While the Russian elite might have well thought Ukrainian NATO accession was a mortal threat, it clearly had other, and most likely better instruments at its disposal to prevent it. Mearsheimer rightfully points out that Russian leaders might have perceived the situation differently. However, he does not elaborate how Western states should pursue their own values and interests on the one hand, and ameliorate such seemingly unreasonable and excessive security concerns from Russia on the other.

Without a doubt, competition over international influence and vastly diverging ideas on what kind of regime should govern in Ukraine have strongly contributed to the unfolding of the Russo-Ukrainian war and the wider Russo-Western conflict. However, there are serious flaws in Mearsheimer’s portrayal of the causes of the Russo-Ukrainian war, wherein an aggressive, reckless, and ideologized Western policy gave Russia no option but to resort to war. This heightens once more the need to engage issues of regime competition with conceptual rigor and sound empirical grounding, as, otherwise, flawed analysis might well bring forth flawed policy.

This article summarizes key results of a study by this author published in Analyse & Kritik.